- HOME

- CULTURE

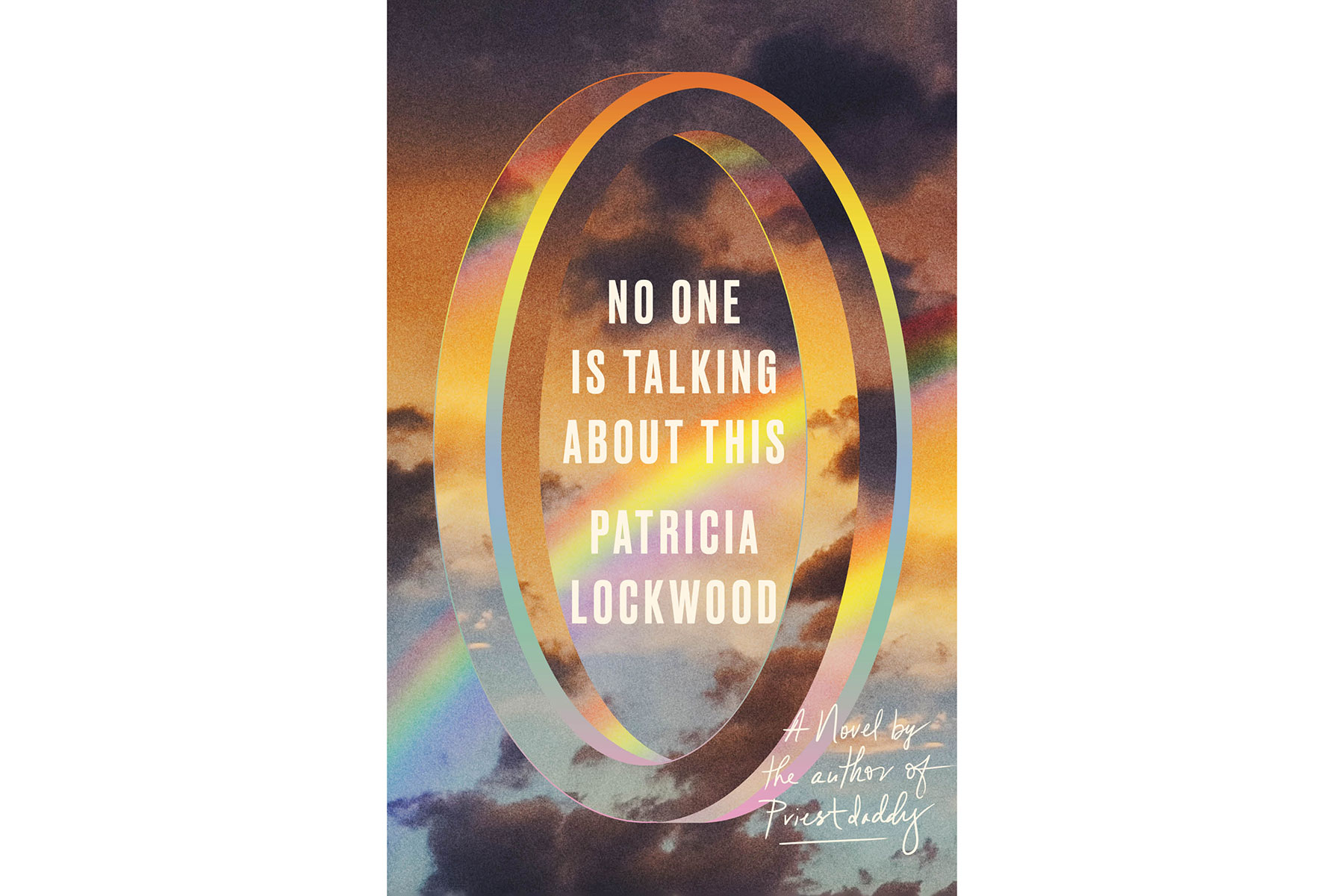

Patricia Lockwood Wins The Dylan Thomas Prize

'As long as I have books, I never feel anything but largely content and intact'

By | 2 years ago

Twitter queen and author of No One is Talking About This, Patricia Lockwood, has just been announced as the winner of the prestigious Swansea University Dylan Thomas Prize. Last year, she was also shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2021. Patricia talks to Belinda Bamber about marriage, metaphor… and teacup pigs.

Q&A with Patricia Lockwood

The first half of No One Is Talking About This is about Twitter (where you currently have 90,000 followers and have posted over 20,000 tweets), and the second half is a moving story about the birth of a miracle baby, during which the protagonist temporarily abjures her online life. Did writing the novel affect your sense of how online and offline worlds interact?

I have always felt them to be intertwined. Even in those moments when I was living my realest and most urgent life, my phone was in my back pocket, and I knew that the stream of some other consciousness was going on in there, electric and alive, as the life goes on in some closed book on your bookshelf. I liked that; I found it meaningful. I wanted to talk about it. That’s my rational answer. My irrational answer is: 20,000 TWEETS? WHAT HAVE I BEEN DOING WITH MY LIFE?

‘What is a human being?’ asks the protagonist of No One. Should we look to books or to the portal for answers?

In both books and in the portal, you are watching people pass: going about their days, eating breakfasts that are both transitory and immortal, taking off one pair of pants and putting on another. Human beings are something that time is alive in for a little while, they are clocks that understand something of their workings. They hear themselves ticking down, and they know that the question is: to what? Both books and the portal are a place to watch that happen, except that in the portal they are real. It’s a question of preference. Do you want the people you’re reading about to have driver’s licences, or do you want them to have been conceptualised by some dead guy in a waistcoat who was mad about the Industrial Revolution?

When you write about entering the portal in No One, I wasn’t thinking of the internet at first – it felt instead as though you’d hinged back your cranium and let me peer inside the portal of your head to read your random, dancing thoughts. It felt eerily familiar and simultaneously alien. How does it feel for you, when we read your words?

It’s true – it’s being spoken of as a specifically internet novel, but my stream of consciousness might look like this even if the internet had never been invented. I would just have to supply all the teacup pigs and new species of tree frog myself, which would have cost a little more effort. Being read is a curious feeling. In Haven Kimmel’s memoir A Girl Named Skippy, she talks about the delicious uncanny sensation she gets when her friend draws her. Being read is a little bit like that for me. You can feel it happening, sometimes all the way across the world.

If Twitter is a 21st century version of neighbourly gossip over the yard fence, what shape will chit-chat take in 2121? How will we connect, and in what language?

It’s going to be SO gross, whatever it is. We’ll have capsule hotels inside our minds, probably, and people will have to come check in for an hour whenever they want to have a cup of tea and a sit-down. This is what happens when you let the tech guys be in charge. They never have a normal sit-down with ANYONE, so they all just assume that things should be moving to the point where we’re inside each other’s minds wearing complimentary slippers.

What are non-Twitter users missing by not joining in that ‘communal mind?

The aforementioned teacup pigs. The feeling of flowing down the bloodstream of the news on a rapidly deflating life raft: you’re about to drown, but at least you’re not missing anything. The sense of being in the know, which is the biggest (the smallest?) teacup pig of all.

Has Twitter honed your brilliance in crafting the delicious pay-off in a sentence, or is it the other way around?

The other way around, I think. If you go back to my earliest tweets, it appears I’m live-tweeting all the sex scenes in Bambi. There ARE no sex scenes in Bambi. So yes, nothing has really changed from then to now. Both the turn of phrase and the subject matter seem to predate the medium.

How would you cope in a global blackout? i.e. no internet, no mobile phone.

Die instantly. Keel over sideways like my cat Dr. Butthole did once when a burglar broke into our house.

You’re a queen of metaphor. Do you savour your favourites like candy on the tongue or is it a gift you can be profligate with, like a singer’s perfect pitch?

I do enjoy them, possibly too much. You’re always encountering those completely grey writers wearing ascots who are like, when you love a line or an image too much, cut it! But I spent too much time as a teenage Christian to ever go for that kind of self-denial. It’s true, though, that metaphors do come very easily to me; often before I have even registered a fact or an object or an event, I am thinking about what it is like. When they come to you that easily, they must sometimes be resisted.

It’s unusual in modern stories to feel ‘the couple’ as the still centre of the story rather than the pivotal source of narrative conflict, but there’s an Austen-esque sense in which Jason, or ‘Husband’ [i.e. your real-life husband who appears in your memoir Priestdaddy, and the fictional ‘Husband’ in No One], is a stabilising Mr Knightley for the reader as well as for the protagonist. Her / your wider family of lovable eccentrics also provides a sense of stability and belonging. Is there a new way of talking about ‘family values’ that isn’t politically weighted and distorted?

I laughed so hard at the phrase “Jason, or ‘Husband,’” so thank you for that. Yes, he is the still point of the turning world, and the rest is the frightening spin all around me. But it is also a characterisation, an act of love. I think I do not engage in normal acts of tenderness, like bringing someone chocolates or washing their car. But I can bathe a person in a better light when I write about them. If his gift to me is stability, then my gift to him is that he goes on this way, that he is an adored and adorable character in some wider memory. I think I was able to do this for my father as well, a much more complicated person. No, I have no new way of talking about family values except this: that you must recognise your own gifts and bring them to the table. What is your role in the commune? What do you cook, when it’s your turn in the kitchen?

What gives you the feeling you so lyrically describe for your characters, of ‘the sun running through you’?

Well, the act of writing itself does, like a pack of joyous animals literally running through my body. It is vigour, it is the feeling that you were made for this world and made to do things in it, that you are a part of nature and the larger mind. I have that feeling when I sing, too, and when I jump hurdles, which I’m also very good at. One of those things is a lie.

Can the word (or the Word, in any religion) help us accept the limits of our human heart? Can books relieve loneliness?

Certainly they relieve loneliness. The question is what else do they do, what do they give us that we can carry into waking life? For a person like me, they actually relieve loneliness so efficiently that as long as I have books, I never feel anything but largely content and intact. But is that better? Do they enlarge my heart and make me more generous, or do they make me yell GO AWAY at Jason when he pops into the room humming reggae just when I’m getting to the good part?

Which books re-centre you when you’ve lost heart?

I reread A.S. Byatt’s The Virgin in the Garden quartet frequently – now THAT’S a woman who knows what colour a glaze is. I reread Lore Segal’s wonderful children’s book Tell Me a Mitzi when I’m sick. I read Maya Angelou’s autobiographies when I want to think about the arc of the 20th century.

When you open a novel, what are you hoping to find?

A good first sentence, and then, as Isak Dinesen says in Out of Africa, for the writer to “go on as beautifully as he has begun.”

If you could save one word for posterity?

Lipstick. That’s always been it for me, I don’t know why.

Which writer, living or dead, is best at sex?

It’s Kafka. But sex, for him, is tying a tiny piece of black yarn around your big toe, which he does perfectly.

Your last words on Earth and first on arrival in Heaven?

I think we can all drop this charade that I’m going to heaven. And I want my last words on earth to be an incredibly freaky scream, so that Jason will always remember me (he’s scared of screaming.)

Are you more in your skin with prose or poetry?

Poetry, of course. But I make the prose into poetry too, so I remain in my skin one way or another: one weird trick.

Patricia Lockwood’s debut novel, No One Is Talking About This, is out now.

MORE CULTURE:

Q&A With The Nevers’ Ann Skelly / 8 Must Read Books On Mental Health / Best Books For Hopeless Romantics