My Love Affair With Virginia Woolf

By

8 months ago

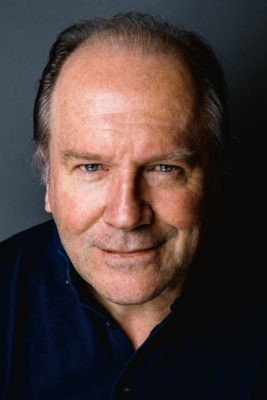

Italian author Chiara Valerio cut her teeth translating Virginia Woolf’s novels

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway is 100 years old in 2025 – and the party is not over, says Chiara Valerio.

Chiara Valerio (© Laura Sciacovelli)

Chiara Valerio: An Escape Room Of One’s Own

It is important to note that my thoughts on Virginia Woolf’s novels (and on Woolf herself) will be radically different once I write them down in English, as I am doing right now. That’s because my written English, although I have translated four of Woolf’s books from English into Italian, is nothing like my Italian. And that’s because I live in Italy, I think and work in Italian. More importantly, I love in Italian, I quarrel in Italian, I studied in Italian and, in my early teens, I read Woolf for the first time in Italian.

I cannot remember the first time I heard of Clarissa Dalloway, but I bet it happened, quite simply, when I read the brief biography of Woolf that is printed at the end of an old Italian paperback edition of Orlando. Orlando was the first novel by Woolf that I read. I was 12, it was springtime, birds sang and somersaulted, and I read Orlando because it is a queer story – and I, around that time, had started thinking that I was a lesbian. Now, after decades of life and miles of pages, I’m rather sure that Orlando eludes every definition and adjective, including queer. Like a human body, Orlando is too vast and complicated to be reduced to labels, tags, adjectives, names, things, or cities.

Virginia Woolf taught me to be an objector. Maybe not quite a revolutionary, but definitely an objector. That is, she taught me to believe in and to trust the fluidity of the world. The world is fluid because, as she wrote many times, ‘the world is vocal’. To be an objector means to escape every kind of totalitarianism – in politics, science, technologies, and love.

‘Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.’ So do I, often. So do a lot of women who decide to throw a party. The actual reason why one throws a party is that one is alive: because they can breathe, and nobody is bombing them every Friday morning. Mrs. Dalloway takes part in the moving feast of life. Septimus, on the other hand, does not. In Septimus’ ears, feast rhymes with beast: his body is back from the war, but in his ears there is no sound of the world around; there are only bombs. In his eyes there is no living person, only dead men walking. Love is a muted memory and the world, for Septimus, is not vocal, but rather muted and frozen. He cannot escape it. Rather than living, he survives.

‘He – for there could be no doubt of his sex, though the fashion of the time did something to disguise it – …’ The same goes for me: no doubt about my sex, and yet the fashion of my time does something to disguise it. For me as for Orlando, this ‘no doubt’ affair is quite unfair, because sex is never one thing. Rather, it is something between at least two living beings.

Sex is a relation, or a process, not really a state of mind – definitely not a state of body. I think the whole of Virginia Woolf’s oeuvre is a huge roundabout, in the centre of which one can find not a single man or woman, but a relation. A relation between humans, or between humans and weather, a tense, a bunch of flowers, a dog, a dress, a cup of tea, a dolphin (in Freshwater, for instance), English history, a ghost, a dinosaur (like for Mrs. Swithin), a word (he, no doubt of his sex). The world is vocal.

As Virginia Woolf wrote in the preface to Orlando: ‘Many friends have helped me in writing this book. Some are dead and so illustrious that I scarcely dare name them, yet no one can read or write without being perpetually in the debt of Defoe, Sir Thomas Browne, Sterne, Sir Walter Scott, Lord Macaulay, Emily Bronte, De Quincey, and Walter Pater – to name the first that come to mind. Others are alive.’ I’ve got a lot of dead friends myself, and they are not imaginary friends. I share some of them with Virginia Woolf, others I don’t. In fact, one of my lovely dead friends is Virginia Woolf herself, and the root of our asymmetric relation is that I read Virginia Woolf. And when I read her, most of the time, I laugh: most of her lines make me laugh.

I do not know how the majority of English readers of Virginia Woolf consider Virginia Woolf, but in Italy, for many years, we have read her exclusively in a tragic vein, denying her a comedic one. In Italian, she tends to be ‘the great writer’: the feminist, the literary critic. She is her illness and her bliss, but not her laughter. We do not read her as an amusing, ironic, uplifting, comedic author. To put it simply: she committed suicide, so she can’t be a funny writer.

Nonetheless, I strongly believe that she is: an endlessly funny, comedic writer. In her letters, diaries, literary reviews, comments, even novels, Woolf is, most of the time, comedic.

What do I mean by ‘comedic’? That word, to me, represents the enduring option, the chance, to live. The chance to leave. Even with stones in one’s pockets.

Chiara Valerio is the author of The Little I Knew, published by Foundry Editions and out on 10 June 2025.