Between Mist & Mountains: A Chinese Adventure Through The Yunnan Province

By

2 months ago

Luke Abrahams discovers China’s most rebelliously diverse province

Lost, found and immersed in the landscapes of Yunnan, Luke Abrahams discovers China’s most rebelliously diverse province.

Your Guide To Yunnan Province, China

Credit: Nicolas Quiniou

I will never forget the first time I watched Lost in Translation. I vividly remember a scene in which Scarlett Johansson walks alone through the streets, gardens and sacred temples of Kyoto in silence. Her only way of communicating is via a nod or a faint smile, and her face screams a thousand emotions, from loneliness to quizzical curiosity. That’s the beauty of Asia for you. It’s a continent lost in translation, from customs to ways of life, culture and, of course, language. No matter where you go or who you come across, you are, at every passing corner, quite literally lost for words in a sea of thousands.

This is very much how I found myself in rural China: adrift, confused and – aside from the company of my companion Nicolas and our guide Steven – deeply solitary. Yet, in all this loneliness, you find a sting of liberation in it all. Here, among a legion of crowds scurrying through Dali’s domestic departures terminal, not a single person looked like me, spoke like me or even dressed like me. It might seem a bizarre paradox, but I oddly felt seen, as if I were the star of my own narrative.

Blending past, present and future, China is unique in the world. The country is a timeless mix of history, strict traditions and infinite possibilities, all thriving in unison alongside a swathe of surprises. From headlines to political ideologies, the name alone conjures up all sorts of feelings: fear, intrigue, mystery and curiosity. Look beyond all the terror-inducing superlatives, and you’ll discover a world of dizzying oxymorons.

Yunnan province has always stood out from the rest of China. Historically, it was most famous for its role as the Ancient Tea Horse Road, a network of slithering trade routes that connected lone travellers – like us – in southwest China with Tibet and the rest of southeast Asia. The route, still used today for its nomadic sense of adventure, gained its name from primary trade: tea from Yunnan was exchanged for horses and even religious instruction between Han and Tibet, from the Tang and Song dynasties to what is now known today as the People’s Republic of China. With 25 officially recognised ethnic groups – Dai, Bai, Wa, Lahu, Hani, Jingpo, Nu, Naxi and Lisu among them – a vast array of rich plant life (an estimated 19,333 higher plant species), and landscapes from jungles to dramatic rice terraces and desolate plateaus, Yunnan is perhaps nowadays best described as China’s most rebelliously diverse state.

Credit: Nicolas Quiniou

That said, this image of a remote, cut-off-from-the-rest-of-the-world abyss is, at times, lost in translation. Legions of tour buses, souvenir stalls and backpacker cafés and inns are part of the humdrum. And its combination of “different” and “ethnic” has made it fall victim to the trendy international crowds, as well as a booming Chinese domestic tourism industry.

We first saw this in Dali City, where its Old Town beams with neon signs and giddy tourists from Beijing who come here to pose alongside its mishmash of purpose-built and Disneyesque sculptures of famous historical Chinese figures. Scurrying around its shops filled with knick-knacks – from teapots to old western records – and street food stalls serving petrified insects, there was a sense of a cultural sell-out. Thankfully, this vision of mass consumerism began to fade by the time we hit Xianglong Village in Xizhou Town – 30 minutes outside downtown Dali and our home for the next two days.

Our digs here, the storied Sky Valley Heritage Boutique Hotel, set in a former Bai-style palace decorated in traditional calligraphy, paintings and ceramics, give the impression of a town still very much in touch with its roving roots. Set under the shadow of Cang Mountain, Xizhou has always been an important trading post along the Tea Horse Road. The village itself is a mixture of cultures, mostly made up of Bai people (Bai merchants travelled extensively from here to Tibet, trading Dali’s tea, marble and handicrafts), and remnants of its past are still very much a feast for the eyes and other senses.

Credit: Nicolas Quiniou

We first encountered this at Xizhou’s daily morning market, a vast abyss of frenetic colour and buzzing chaos. Locals descended on its mad streets to buy groceries – from sticky breads and rice noodles to fresh shoots, live fish and huge vegetables of all varieties. In between, restaurant vendors tempted hungry bellies with all sorts of Dali delicacies – clay pot fish, steaming Xizhou Baba (a sweet bread) and wild mushroom hotpots – while local ladies wooed myself and Nicolas with silk weavings and portraits illustrating Yunnan’s various wild landscapes. The rest of the city is very much a living museum. Bai-style courtyard houses make up most of the fringe (the Yan Family Compound, now a museum, is its best example and well worth a visit), and the road up to Cangshan Mountain, a sacred heritage site known for its precious marble, paints a picture of life here before electric cars and scooters replaced yak- and horse-drawn carriages.

The vision of Yunnan’s splendid isolation continued on the road to Lijiang. Driving south, the hustle and bustle morphed into a world of towering rice terraces and empty roads to nowhere. Eventually the road ended abruptly, and we arrived in Stone Dragon Village. This was the first time we encountered the real, raw and dusty wild China cut off from the rest of the world. A cluster of Bai carpenter families, the town is a patchwork of bric-a-brac houses surrounded by wildflowers and snaking rivers that trail their way into the mighty Yangtze. Daily life in this part of China is unequivocally humble, simple and silent. A mirage of cows and sheep add to its pastoral landscape charm alongside quick-witted farmers eating with their families and village elders playing cards in clouds of cigarette smoke.

Time passed and our western faces stuck out like a sore thumb as shy locals offered us food with a friendly nod and smile – a banquet of Bai delicacies from winter pork and smoked sausage to fried azelea flowers and broad beans – and after a traditional performance and singalong courtesy of the village’s children, we hit the road again for the mountains.

Credit: Nicolas Quiniou

A thick cloud of ethereal mist welcomed us into the grand city of Lijiang, kingdom of the Naxi people, and home to Amandayan, our sanctuary of peace for two nights. Crowned by the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, it serves as Lijiang Old Town’s imposing backdrop and is often described as one of the most beautiful places in China. Between its cobblestoned streets and historic teahouses, a portrait of Naxi life is drawn throughout its storied temples and inns. The segregated group are known throughout China for their unique shamanic, literary and farming practices, all influenced by the Confucian roots of Han Chinese history. While the now commercialised city remains their stronghold, nods to their traditional and authentic customs still ooze throughout Ciman Village, a small cooperative 8km outside of downtown Lijiang.

A part of Aman’s cultural offering, here we spent time learning about social traditions, including the art of Dongba (an ancient Naxi script, predating Traditional Chinese), courtesy of a writing class. In between a banquet lunch – again served in silence with a nod and a smile – of hotpot favourites, we made our own drums bound with yak skin that we later bashed while being treated to a Naxi dance routine.

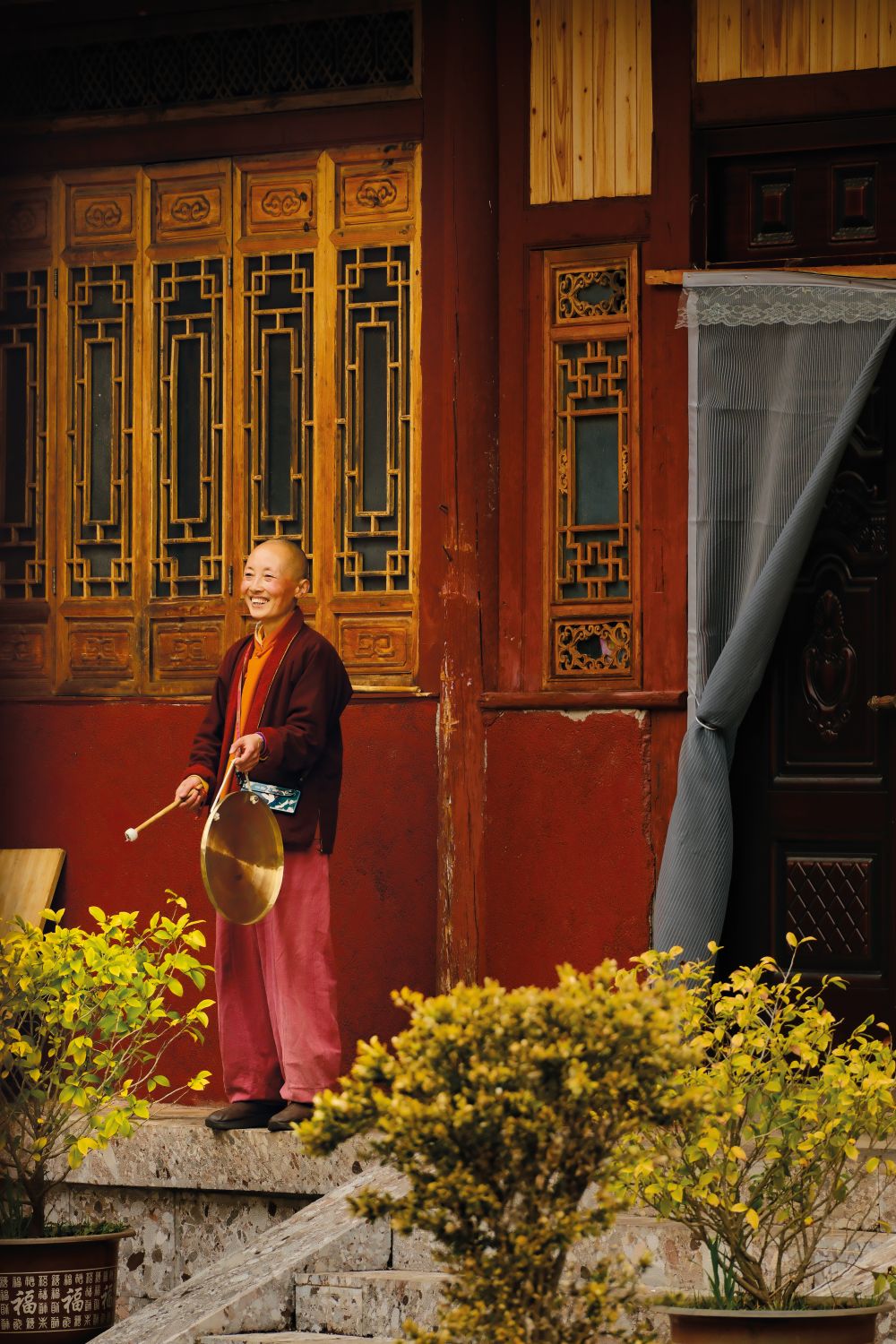

Later, we ascended the hills to explore the historic Wenfeng Temple. Set on the foot of Mount Wenbi, the golden monastery was first founded under 17th-century Naxi king Mu Tian Wang and was once used to welcome the supreme academy of the Kagyu sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Now, it’s mostly a place to engage in meditations and Buddhist teachings. With a mise-en-scène of incense trail plumes enveloping the cascading falls and blooming cherry blossoms, it’s a place to reflect and unwind in the privacy of your own stillness.

Credit: Nicolas Quiniou

After exploring the winding roads of Daju through the mighty Tiger Leaping Gorge, the Tibetan plateaus and grand temples in Shangri-La, our adventure ended in Shanghai. We skipped The Bund for seclusion 50 minutes outside the city at the Amanyangyun resort, and, like our rural adventure before, we found ourselves again in a state of cultural immersion: Ming and Qing dynasty houses and ancient camphor trees stand side by side and undisturbed for hundreds of years, while the expansive millennia-old forest set metres outside of the resort transports you into a desolate vision of a Shanghai lost in time.

Beyond the rooms, Nan Shufang is Amanyangyun’s spiritual heart. The cultural centre, inspired by the scholars’ studios of 17th-century China’s literati, is a throwback to the country’s growing appreciation of its imperial past and is where guests can partake in everything from the art of incense making to calligraphy. It dawned on me as we left that this private sanctuary steeped in antiquity serves as a reminder of what Yunnan once was: the final frontier of storied epic adventures, and a remnant of a history perhaps now best described as wholly lost in translation and lost in time.

BOOK IT

Cazenove+Loyd offers a ten-night trip to the Yunnan region of China from £8,500pp, based on two people sharing, including international and domestic flights, transfers, touring and some lunches (cazloyd.com).

Luke’s flights from London Heathrow to Shanghai and Shanghai to Dali had a carbon footprint of 3,379kg CO₂e. ecollectivecarbon.com