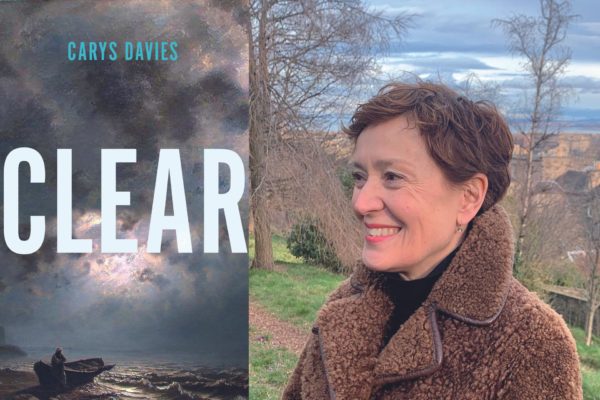

Interview: Julia Armfield On Her New Novel, Private Rites

By

1 year ago

The C&TH Book Club pick for May/June is Private Rites by Julia Armfield

In this month’s Book Club, Julia Armfield talks to Belinda Bamber about the apocalypse, queer writing and why water is her narrative medium.

C&TH Book Club: Private Rites by Julia Armfield

© Avery Curran

Belinda Bamber: Private Rites is set in a time of apocalyptic floods. The end of the world is nigh, yet three sisters, Isla, Irene and Agnes, have to organise the funeral of their tyrannical father and continue to navigate their day-to-day living, loving, working and squabbling. What did you enjoy most about writing this book?

Julia Armfield: Something I’ve been preoccupied with throughout my career is the concept of a pervasive norm – the way that banality and dailiness always assert themselves no matter the extremes people find themselves in. This can be a good thing, inasmuch as it shows how adaptable people can be, but it also signifies a kind of apathy and powerlessness in the face of an overriding system, and I’m extremely interested in that. Writing this novel was, to some extent, an exercise in confronting that apathy – in considering the things it feels most likely will persist when everything else falls apart (work, commuting to work, complaining about work etc) and trying to express what a waste of time that all is!

BB: Water is also the medium of your debut novel Our Wives Under the Sea. Where does this preoccupation come from? Might your next novel also feature the life aquatic?

JA: I thought about this a lot after Wives came out, because I don’t think it was really a conscious preoccupation until I looked around and realised how prevalent the ocean and the water is in a lot of really formative lesbian media. It’s a trope you start to see everywhere when you look – in movies like Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Ammonite and Water Lilies, novels like Sara Jaffe’s Dryland, Kirsty Logan’s The Gloaming, even many of Sarah Waters’ novels are tangentially set by the sea. I think there’s something in the image of water that speaks to duality – the idea of being one thing on the surface and another beneath, which can be so key to the queer experience. And so too, in many of these texts, I feel like proximity to the sea or to the water somehow goes hand in hand with the concept of coming out or coming into oneself more fully, the idea of an odyssey or a baptism, of moving through water to become more fully yourself. It’s odd when you start recognising that an image is so prevalent in things you’ve read and watched and that that might be why it’s seeped so thoroughly into your own work. Although that said, I think I’m unlikely to go three for three on wet novels!

BB: I enjoyed your description of the novel as ‘King Lear with lesbians at the end of the world’. What does the sisters’ queerness bring to the story?

JA: I think it is the story – when I was mapping out the arc of this novel, I became very interested in the way that disaster epics and apocalypse narratives in film and literature tend to really ringfence the importance of the traditional nuclear family. In an emergency, the priority is to get your family in the bunker and keep them safe. What I wanted to do was deconstruct that a little from a queer perspective and consider what would happen if your nuclear family was not safe, or worth keeping safe, and how your disaster narrative would unfold in that case – and who would be in your bunker.

BB: Do you see yourself as part of a tradition of queer writers? If so, who has inspired you?

JA: I think it’s hard to say, since we’re all just writing in the moment and it can only really do you harm to zoom out and try to see yourself as something larger – however, I’m inspired by Andrea Lawlor and Sarah Waters and Alison Rumfitt and people making incredible queer cinema like Charlotte Wells and Rose Glass and Luca Guadagnino, and old horror auteurs like James Whale. I particularly love the way you can scratch my favourite genre – horror – and find queer writers and artists and filmmakers everywhere.

BB: There’s a Shakespearean character arc to the way in which adversity brings the sisters self-knowledge, yet also a pantomime hilarity to some of their bitching. When you started writing, did you think of the story as tragic or comic?

JA: I think that’s a great catch because I wanted the relationships and the core of the novel to be as realist as possible, despite the extreme setting, and so I really tried to blend comedy and tragedy evenly throughout. I like to mix horror and genre elements with really mundane realism, which is sort of a tragicomic balance of its own, and I’ve never been particularly interested in writing something completely grimdark without any levity. Some of my favourite novels, like Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love and Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, are my favourites because they pull off this balance to perfection – something terrible is happening, but you recognise yourself within the lightness, rather than the dark.

BB: The atmospheric opening, with its sense of foreboding, reminded me of Shirley Jackson novels. There are mystic signs, a fear of ‘bad spirits’, a hint of witchcraft, macabre sacrifices or savage pagan rituals – the idea that Armageddon will panic people into extreme acts of desperation, alluded to in your title, Private Rites. Did you always have that as the working title, and when did you first become interested in humanity’s dark side?

JA: No, the title was a very late decision, actually! I’ve always been interested in horror as a genre ahead of all others – there are a lot of instances in the novel of really quite young children watching horror movies or becoming preoccupied with dark topics or overhearing unsettling things, and to some extent this is just because that’s what happened to me! I think that that bleed can often happen early – the realisation that the world isn’t a safe place or the recognition of the dark things that people feel. I wanted to emphasise that a little, as I think it can shape the way we see the world later.

BB: Eyes are everywhere in the novel: looking, scrutinising, secretly following characters’s movements, or turned inwards in self-reflection. Was it a conscious device as you were writing?

JA: Yes very conscious – I think this is one of the core devices I tried not to overplay but simultaneously knew I had to foreground to give the ending a hope in hell of making sense. It’s always very hard to tell whether you’re overstating a point when you’re in the thick of writing but when it came to editing I actually realised I needed more! It’s a novel about watching and being watched and about the sensational of powerlessness that can accompany seeing things unfold in front of your eyes.

BB: Do you have any ‘private rites’ around the process of writing?

JA: I work fulltime alongside my writing so I’m not really afforded an awful lot of space for ritual. This is something I think I’ve started saying quite a lot, actually: there’s a fallacy that writing has to take place in this rarified space when conditions are perfect – you’ve got no demands on your time, all your tasks are complete, you’re in a meadow with a dandelion, whatever – and I think this is a myth that allows writing to become an elitist pursuit and one only open to those with the time and the means. In reality, you just have to write whenever you can and fix it later if conditions don’t allow it to be the best writing you’ve ever done. Getting it done is, to me, the only point.

BB: How did your own religious upbringing influence your writing?

JA: I didn’t have a particularly religious upbringing but I am extremely preoccupied with Catholicism in a way I think you can’t help but be if you were brought up adjacent to it! I’m very interested in the way it inserts an awareness of ritual and rules into one’s life very early and creates a possibility for guilt and shame that comes separately to the behaviour one learns at school or at home. It’s another layer to things.

BB: You’re brilliantly perceptive about the ins and outs of love, sex, commitment and day to day relationships/marriage, an aspect that keeps the apocalyptic story line very grounded. Which books or authors have given you insight into the joys and trials of love? Or can we only learn from experience?

JA: This is a great question – once again I’d recommend Geek Love (Katherine Dunn), then probably The Age of Innocence (Edith Wharton), Happy All The Time (Laurie Colwin), America is Not The Heart (Elaine Castillo), It (Stephen King; actually mostly everything by Stephen King is weirdly romantic), and Greta and Valdin (Rebecca K Reilly) – different kinds of love in all of them and all equally formative.

BB: There’s been a noticeable increase in dystopian novels, in the face of climate change and war around the globe. Which have most influenced you?

JA: I actually haven’t read an enormous amount of contemporary fiction just recently as I find that when I’m in the thick of editing, there are only a handful of things I can usefully reread. However, I’m very much looking forward to Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang.

BB: Do you hope the end will come with a bang or with warning? What or who would you take with you if you could make an ark?

JA: A warning, as I presume otherwise I wouldn’t have the chance to build an ark, and I’d need to take my wife and our cat and our friends and their cat on the ark, mostly just to see what the cats would do.

BB: The sisters’ father is an acclaimed architect whose fragile buildings don’t survive the floods. Where would you build your bunker and who would design it?

JA: Probably I would, just so I only had myself to blame when it fell down. One of my favourite episodes of The Simpsons briefly involves Homer finding a set of Gary Larson cartoons in a ready-made bomb shelter and then not understanding any of the jokes, so I’d probably also need a Gary Larson calendar in my bunker just to pass the time.

Private Rites by Julia Armfield is published on 11 June by HarperCollins, £16.99