Review: Jews. In Their Own Words, The Royal Court

By

3 years ago

The damning legacy of antisemitism, dramatised from interviews

A new play by journalist Jonathan Freedland at the Royal Court dramatises interviews in a bid to explore the roots and legacy of antisemitism in Britain. Caroline Phillips reviews.

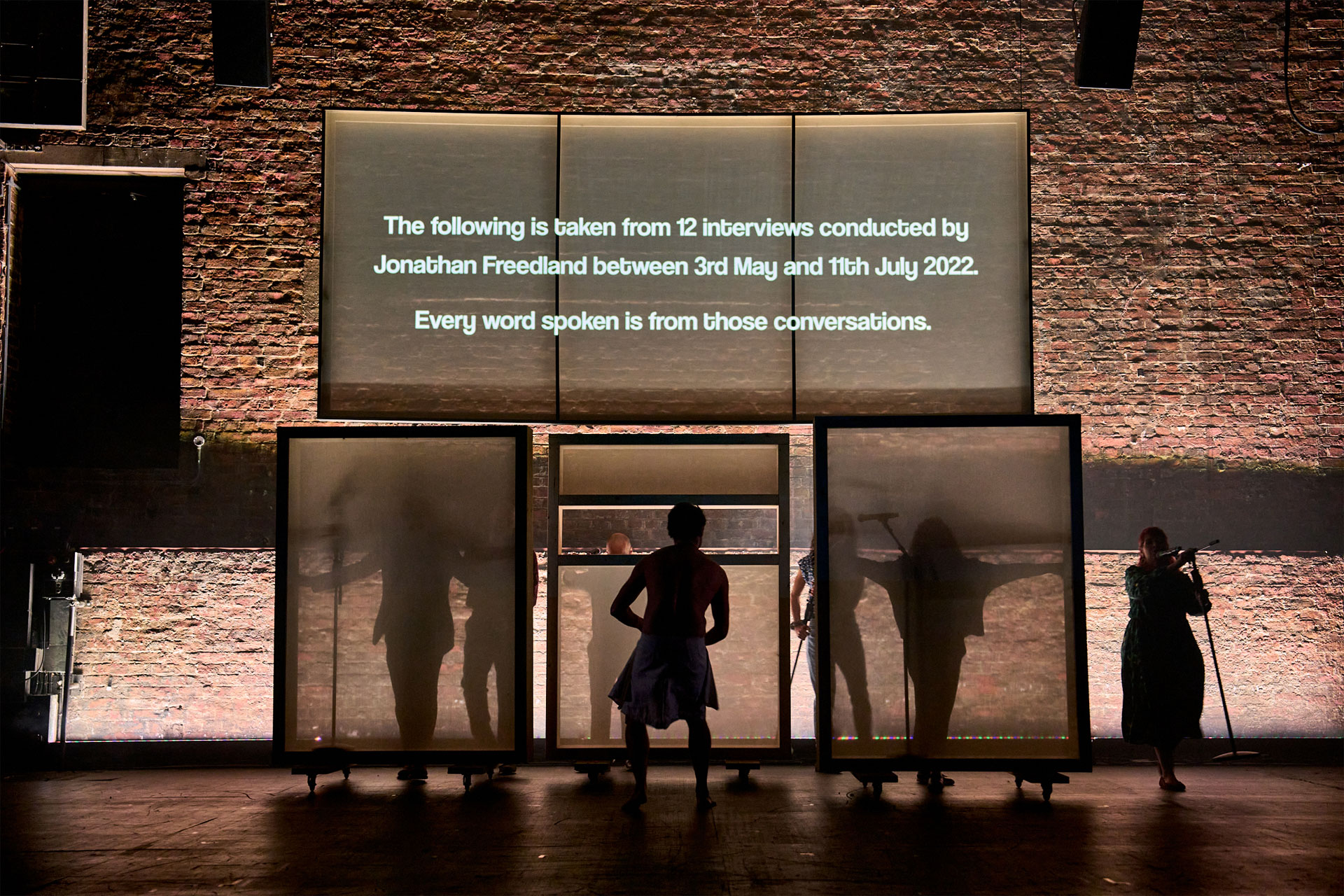

© Manuel Harlan

Review: Jews. In Their Own Words, at the Royal Court Theatre

Jews make up less than one per cent of the UK population. Yet a quarter of all hate crimes in the country are antisemitic. In the week that the Jewish Chronicle reported on this harrowing statistic, I went to the Royal Court to see journalist Jonathan Freedland’s ‘Jews. In their Own Words,’(JITOW). I have a Church of England mother but grew up with antisemitism: the curious sort from my Jewish father (the son of observant parents) who directed it against his own kind — arguably a manifestation in part of self-hatred and a perverse desire for assimilation. (‘Jews can be the worst antisemites,’ a Jewish friend explained.)

That side of the problem of antisemitism is not explored in Freedland’s play in which seven actors voice the verbatim words of Freedland’s 12 interviewees, (the idea of co-creator and actor Tracy-Ann Oberman). But nearly every other aspect is. It’s wide-ranging: from historical (Jewish money lenders to supposed baby killers) to contemporary (the issue within Corbyn’s Labour left); from literature (Jewish stereotypes in Chaucer, Dickens, Shakespeare and, of course, why did Dracula drink blood and hate crucifixes?) to current conspiracy theories (Jews put Coronavirus in Coca Cola). Power. Money. Blood. Israel. Zionism. Centuries of prejudice and persecution. It covers all this ground and more, which is perhaps too much.

The verbatim words are those of writer Howard Jacobson, MPs Margaret Hodge and Luciana Berger, political commentator Stephen Bush and Tracy-Ann Oberman herself, but additionally they come from unknowns: a social worker, a doctor and Phillip (with two ‘l’s as he states) Abrahams, a decorator, who delivers one particularly jaw-dropping revelation about his Turkish newsagent blaming the Jews for coronavirus. The seven actors — directed by Vicky Featherstone — slip easily between the different characters they play.

The play’s aim is to look at the liberal left, the hidden antisemitism that seeps into even the most supposedly anti-racist circles. It was written in response to the Royal Court’s own bias issue: in 2021, an avaricious billionaire character named Hershel Fink (a Jewish name, a stereotype, a harmful antisemitic trope) appeared in a play there called Rare Earth Mettle (before his name was changed to Henry Finn); and let’s not forget the criticism targeted at Caryl Churchill’s Seven Jewish Children back in 2009, written shortly after Israel’s killing of over 200 Palestinian children in its bombing of Gaza.

JITOW shows how antisemitism —both overt prejudices and hidden assumptions— come into private and public discourse . There’s a revealing discussion about anti-Zionism as a guise for antisemitism; and on the display boards that the actors wheel on, we see some of the shocking, vitriolic tweets sent to Berger, Hodge, and Oberman. The play aims to expose the roots and damning legacy of antisemitism in Britain, and succeeds in that. It manages to show the deep personal and painful cost of both physical and verbal attacks. Most important is its message that anti-Jewish racism is unique, less visible and somehow excusable as it’s directed against a minority that’s caricatured as rich and powerful and with disproportionate influence.

But it’s hard to sustain dramatic interest —(in the same way that then artistic director Nicholas Kent’s plays on testimonies and enquiries on the Iraq War at the then Tricycle Theatre were hard to dramatise). JITOW’s medieval re-enactments of the history of antisemitism lift it as does the singing and dancing to the song It Was the Jews That Did It lift it (in an uncomfortable Springtime for Hitler kind of way). But it’s still too didactic and, overall, the sense is not of a cohesive whole. It moves to the denouement of the characters saying what they’re not: rich, money grabbing and so on. And then pleading for the stereotyping to stop. But I’d had enough by then. The seats in the theatre downstairs are comfy, squishy leather ones. The only comfortable thing about the evening. But still I found myself looking at my watch after an hour. At one hour forty without an interval, it felt too long.

At the Jerwood Theatre Downstairs at The Royal Court until 22nd October. royalcourttheatre.com.