London’s First Statue Of A Postpartum Mother Is A Vital Addition To The Public Imagination

By

2 months ago

Mother Vérité can now be seen on Portman Square

From stretch marks to swollen bellies, a groundbreaking new London sculpture gives visibility to the realities of postpartum life long erased from public art and imagination. Olivia Emily meets Rayvenn Shaleigha D’Clark, the artist behind Mother Vérité.

Mother Vérité: Refiguring Postpartum In Bronze

For centuries, the arrival of royal babies (and the wellbeing of their mothers) has been proclaimed on creamy parchment, signed by doctors and witnesses, framed and displayed on an easel outside Buckingham Palace. It’s neat, clean and steeped in tradition.

But Prince William and Princess Catherine of Wales – then the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge – quietly sidestepped this longstanding practice with the births of their three children. George’s birth was announced first to the press, while the arrivals of Charlotte and Louis were revealed initially on social media, with the formal palace notice following later.

They did, however, observe another modern convention established by William’s parents, the late Diana, Princess of Wales, and the then Prince Charles. Shortly after each birth, the new parents posed for photographs on the steps of the Lindo Wing, Catherine cradling her newborn while donning a dress, perfectly pruned hair and a glowing smile.

The private maternity unit, part of St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, has become one of the capital’s most recognisable backdrops for royal milestones, though the association is relatively recent. Charles, Anne and all royal children before them were born at home. The tradition itself was initiated by Princess Anne, who appeared on the same steps in 1977 after the birth of her son, Peter Phillips – the first royal to be born without a title in more than 500 years at the request of his unconventional parents.

When Charles and Diana followed with a carefully staged photoshoot in 1982, the Lindo Wing became synonymous with polished royal birth announcements – but many new mothers can’t help but wince when they see them. Instead of rest and recovery, the postpartum mother has been styled, dressed and plonked before the cameras, reinforcing another idealised expectation of the fourth trimester – a period more accurately defined by physical recovery and change than glamour. Both Diana and Catherine even donned high heels.

View this post on Instagram

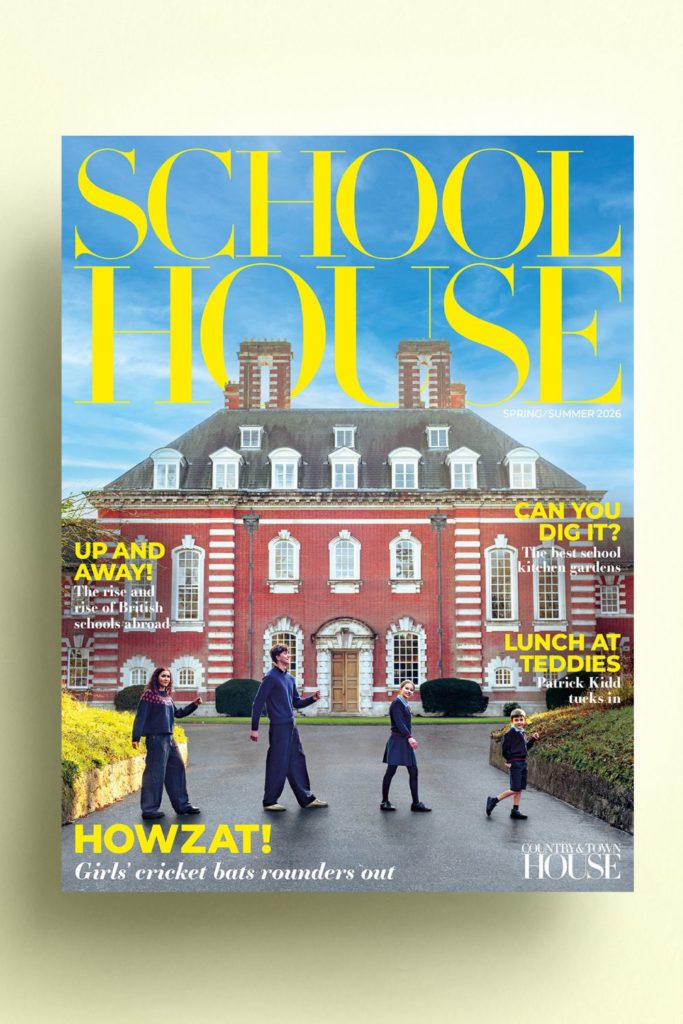

Against this backdrop, the unveiling of a new bronze statue on the Lindo Wing steps in October felt positively radical. Created by British digital sculptor Rayvenn Shaleigha D’Clark in collaboration with Chelsea Hirschhorn, founder of parenting brand Frida, it is London’s first public statue of a postpartum woman.

Titled Mother Vérité, the seven-foot mother stands proud and unapologetically. Cradling her newborn at her waist, her breasts are engorged with her hand planted on her hip. She wears only disposable postpartum boxer-style pants, stretched over her still-swollen belly, where a linea negra can be seen.

Mother Vérité is modelled on 40 women – real post-partum women artist Rayvenn travelled across the country to meet, study and digitally scan before casting the final work in bronze. ‘A really big part of this project was about giving women a safe space to have that conversation about what they’re currently going through,’ she tells me over Zoom. ‘It really entailed getting in touch with as many women as possible who were willing to let me into quite a vulnerable time within their pregnancy journey – allowing me time with them and their very young children, to scan them and to really have quite a dynamic conversation with them.’

Increasingly known as the fourth trimester, the first 12 weeks after giving birth is a serious period of upheaval for mother and baby. Despite the obsession with a ‘bounce-back’ body, this is a period of intense physical change and recovery for new mothers, as well as emotional fluctuations and immense learning. ‘It’s a very precarious time for new mothers,’ Rayvenn says. ‘But the whole experience [creating Mother Vérité] was really lovely because I not only saw the dynamic with their kids, but I saw women reflecting very differently on a very diverse range of pregnancies – whether they’ve had their first or their third child.’

British digital sculptor Rayvenn Shaleigha D’Clark is the mastermind behind Mother Vérité. (MTArt)

As with all of Rayvenn’s characteristically hyperrealistic sculptures, created with the help of cutting-edge 3D modelling, Mother Vérité’s skin is impressively detailed. A linea negra climbs her belly, veins score her hands and stretch marks criss-cross her body – details the first rendition of the statue, formulated by AI, excluded. Ravynn’s software ‘couldn’t visualise cellulite or stretch marks,’ the artist tells me. ‘The computer would just crash. The software wasn’t doing it. So it became a real priority. How do we feed through those intricacies about the female form – the curves, the shapes – that technology very actively seeks to erase?’

The time to counter blemish-free AI formulations like this is right now. ‘By 2050, 75 percent of what we look at will be AI based,’ says Marine Tanguy, entrepreneur, researcher and founder of MTArt, the agency that represents Rayvenn and recommended her to Frida founder Chelsea for the job. ‘The biases that are being created right now are about to be amplified.’

Doing initial research and seeing that AI generated model gave the team something to counteract, Rayvenn recalls: ‘We very quickly understood that the visual absence of postpartum and women’s bodies on a public level is really influencing AI. So for the artwork, we were really thinking, let’s go back to the body, let’s go back to authenticity, and let’s really bring out all the things that AI and Google are missing, and struggle to prioritise in their visual nature.’

In a city where 97 percent of sculptures are men looming above us on a pedestal, Mother Vérité is an important addition (to scare you: there are more statues of animals than there are of women). ‘Mostly what we see erected on pedestals is a representation of a certain type of wealth, power and gender,’ Marine says. ‘Very rarely will that be women – and even more so topics that deeply affect women like postpartum. There are loads of studies showing that we don’t empathise as much with the people we don’t see, so it’s really important to visualise postpartum like this.’

(MTArt)

A collage of scores of women, Mother Vérité is a sort of every-women – and racially ambiguous thanks to the sheer diversity of women in Rayvenn’s study. ‘When it comes to maternal health, as a privileged white woman, I get substantially more attention and care than someone who is Black,’ Marine says. ‘And if I was from a working class background, it will yet again be different in terms of the attention that will get. There are studies proving you are not listened to in the same way. I think that it’s really important that this is not the postpartum of someone. It is the postpartum of everyone. And that makes a great representation of London, too.’

The bronze Mother Vérité is cast in is just as important. ‘It is a very tried and tested material in terms of monumentalism,’ Rayvenn explains. ‘And we want to elevate the iconography of this particular artwork in the same way that bronze has elevated the people actively commemorated in our streets. There are more statues of men named John – real or otherwise – than there are of women or women of colour in London.

‘We are still prioritising, bolstering and retaining the rhetoric of those projects,’ Rayvenn continues. ‘We are actually being told by the government that we’re not removing them, we will re-contextualise them. This is our history. This is what we are putting forth and elevating. That’s completely fine, but actually, what other and new stories can we enter into the lexicon? And how can bronze and materials like stone and marble be used as an equal catalyst to elevate storytelling in the public realm in the same way?’

‘This is not just something a few women go through,’ Marine adds. ‘This is to do with the many things society should actually look at, and can inform how we care for others. A society that doesn’t care is a society that we should be worried about.’

Following her Lindo Wing photo call, Mother Vérité was moved to Portman Square for Frieze before being whisked off to Miami for Art Basel. She’s now back in Portman Square, ready for all Londoners to see. Eventually, she will be donated to the healthcare system.