Jamie Gill on Delivering Diversity

By

3 years ago

‘It’s never going to change unless it’s top down'

CEO of Roksanda and British Fashion Council board member, Jamie Gill has beaten the odds to rise to the top of the fashion tree – both as a BAME gay man and a kid who hailed from a working class background in the Midlands. Former ELLE editor, Farrah Storr, shares a similar backstory and discusses with him why the first step is to make a business case for diversity. Hopefully, the rest will follow…

Buy a copy of Great British Brands 2022 here

Jamie Gill on Delivering Diversity

To the naked eye, Jamie Gill is fashion personified. He’s a sharp-suited, immaculately mannered sort of chap, the type who will hold the door open for you while giving you his thoughts on the latest Balençiaga collection. He sits on the Board of the British Fashion Council and has the not insubstantial job of CEO of Roksanda, one of the world’s most exciting luxury fashion houses. You could hate him – if he wasn’t such a nice guy. You could also dismiss him as ‘just another fashion type’ if you didn’t know the whole story. And the whole story, by the way, is really worth knowing.

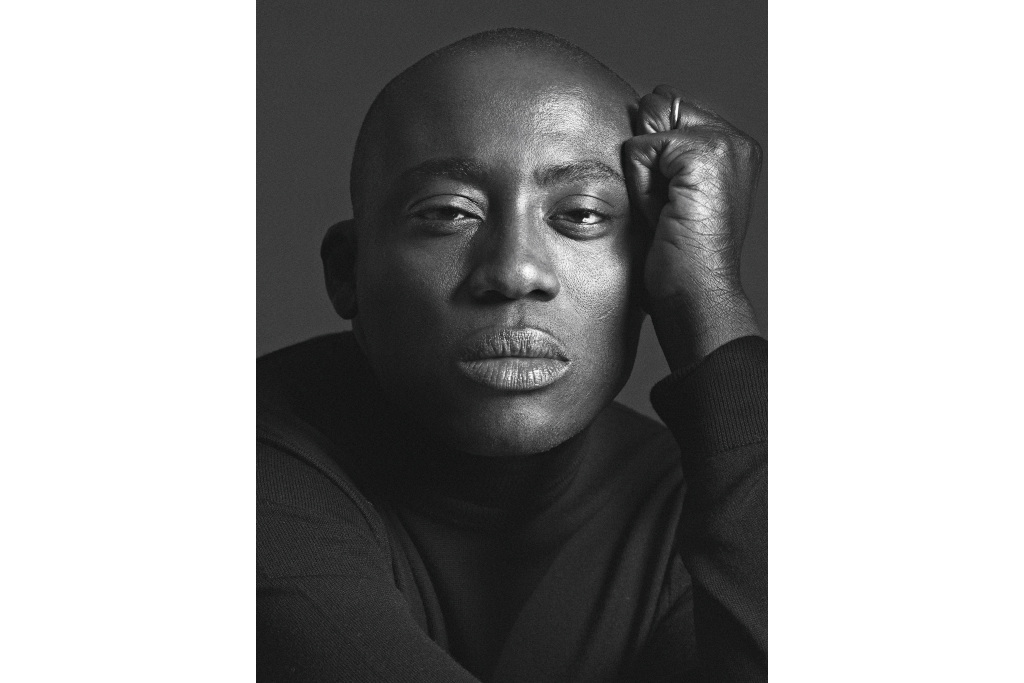

Jamie Gill (Portrait by Luca Strano)

Jamie Gill is, after all, an Asian man from a Derbyshire mining town who had not a single fashion connection when he started out, but has somehow gone on to become one of the industry’s most powerful new players. The story of how he did that is as complex as it is eye-opening – not only about race but also about the power of social mobility and the cultural nuances that make that climb steeper for some than for others. Most of all, however, it’s a story about resilience.

Like most modern day meet-cutes Jamie and I first crossed paths on Instagram when I was editing ELLE magazine. He slipped into my DMs saying we should grab a coffee. We had friends in common. We both worked in fashion. Frankly, why had it taken so long?

It soon transpired that we shared other things in common: namely we were two of only a handful of BAME leaders in the fashion industry. Jamie is from an Indian background; my father is Pakistani. Those two things would not be so striking were it not for the fact we’re outliers in an industry that has spent the last 18 months talking fervently about diversity. What’s more, both Jamie and I come from solid, working-class corners of the country. I am from Salford, home to Strangeways Prison and Shaun Ryder. Jamie is from Denby, a small East Midlands town famous for its former mining pits and pottery. To be BAME and make it in fashion is one thing. To be BAME and come from a forgotten corner of the UK to make it in one of the most competitive, heavily networked industries in the world is a whole other story.

‘I think last summer made me wake up to the diversity issue,’ says Jamie, speaking from his West London home. ‘If you remember, Caroline [Rush, CEO of the British Fashion Council] invited everyone from a BAME background in the industry to a meeting – 163 of us came, from all different levels, and that was it.’

Edward Enninful is British Vogue’s first black editor and has featured a more diverse range of people on the cover since his tenure, including Malala Yousafzai (Photograph: Mert & Marcus)

I remember the meeting well. It was striking to see the industry’s BAME population on one Zoom call. There were names I knew, of course: Edward Enninful, editor-in-chief of British Vogue, Imran Amed, founder of The Business of Fashion and stylist Julia Sarr-Jamois. But, like Jamie, it was sobering to see how few of us there were, particularly at the very highest level.

‘You wouldn’t think fashion has a problem because of our image,’ says Jamie. ‘Ad campaigns, runway shows, parties, events, the assets, the Instagram, the influencers – they are very diverse. It’s so progressive. It’s different ethnicities, different sexualities, different body shapes, it’s gender fluid. It’s everybody’s welcome. Well, anyone is welcome as long as you’re cool,’ he laughs. ‘That’s the only entry card – don’t come in a suit and tie!’

Like most of the creative industries in the last few years, much of the fashion world has worked hard to try and shake off its image of privilege and inaccessibility. When I was growing up in the ’90s, I could name every single model of colour – Yasmeen Ghauri, Yasmin Le Bon, Nadège, Alek Wek and, of course, Naomi Campbell. I struggled more with the big designers – Azzedine Alaïa, perhaps, Rei Kawakubo, Issey Miyake.

The catwalks are now filled with models from a true plurality of heritages (and, it should be said, body sizes, though interestingly this still feels like one of fashion’s last big taboos). From a design perspective, we have Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing, Mancunian-born Maximilian Davis, Grace Wales Bonner, Osman Yousefzada, Alighieri’s Rosh Mahtani, and Rejina Pyo. This is not an exhaustive list, of course, but the point is we have a list. It is a starting point, though arguably a small one.

Osman Yousefzada was told when he started out in fashion that he had to shy away from his heritage in his designs (SS22 pictured above) to conform to the elite fashion environment

What is perhaps more intriguing is what happens when you move further up the fashion chain, into the C-suites and boards. While there has been much talk about the need to diversify at entry level – fashion assistants, writers, pattern cutters, design assistants – few have pointed the finger higher up. One suspects because higher up is not as visible. Few know the ethnic and socio-economic background of those truly at the top. And not to know, perhaps, is the point.

‘It’s never going to change unless it’s top down,’ says Jamie. ‘It has to be board, executive level, management (then) team down. To be fair, it has sparked Richemont and LVMH to find non-executive board members of colour as well as bringing in heads of diversity and inclusion. But ultimately, the fashion industry is run by a handful of macro players and if it’s going well and the talent is delivering, why are they going to rock the boat?

‘You see people holding the same high-level seats for a long time. And to some degree, fashion celebrates that. Because you’re seen as mature and visible after so much time, so it glorifies that seat. At that C-suite level with some of the macro players there’s also still that social bias against someone who is different to them.

‘If you grew up in a certain way and are still friends with the people you went to school with and your neighbours are of a certain ilk, other people can seem quite alien. Someone like me is trying to challenge that because I’m part of a world now that I never grew up in. So you have to have a thick skin. I have always had my headlights on. People will ask you, “Where are you summering this year?” as if it’s the most normal thing in the world. Or, “Where do you ski?” I mean, I’d never skied before! It was something that my family just didn’t do.’

Rejina Pyo moved to London in her early twenties from South Korea and has seduced a stylish audience with her modern lines mixed with antique details

Jamie grew up in Derbyshire where his father ran a takeaway business and his mother worked part-time for Derbyshire constabulary. He tells me he was the only BAME child among a thousand Caucasian kids at his comprehensive secondary school. He was also, he knew from an early age, gay – a fact further complicated by the sheer absence of gay South Asian role models.

‘Being gay in the 90s was still a social taboo in man circles,’ he says. ‘Back then who did we have? It was Lily Savage, Dale Winton and, eventually, Graham Norton. But they are the caricatures. They addressed being gay in a comical way, so in my eyes it wasn’t positive. Any conclusion I drew from society then was that it was silly. So for a long time I grew up thinking I was ill. Perhaps it would have been different if I had found a South Asian gay role model, but I never did.’

He loved fashion and the arts, he tells me, but if he’d told his family these were the interests he wanted to pursue, ‘they would have thought: “Something’s not right here.”’ He eventually came out to his family aged 22.

‘Fashion would have been unpalatable to my family and to the wider community. It would have been, “What is he doing? Where can that possibly lead to?” and “Why on earth are you designing women’s clothes?”’ So Jamie studied architecture instead, but when the financial recession of 2007-8 impacted architecture and construction it was almost impossible to build a viable career in those industries. So in 2010, Jamie joined Deloitte’s graduate training programme (following a friend on the scheme who seemed to be having a good time), and this is where his Damascene diversity moment took place.

‘The firm just seemed to be looking after its people,’ says Jamie, ‘and I remember that in those first two weeks it was clear diversity and inclusion were at the heart of what it did. Its clientele was international, so it needed a workforce that represented its clients. That was where it was really progressive. They asked you about your sexual orientation, your ethnic background, and there was a support programme for everyone from a diverse background.’

Naomi Campbell and Julia Sarr Jamois are recognisable BAME names in the industry, but it is striking how few there are. Pictured: Naomi Campbell (Photo: Shutterstock)

Making a ‘business case’ for diversity is seen by some as too cynical. After all, why should there have to be a business case to promote what should be a natural priority? Yet Jamie is a realist. ‘Of course, we want it to be a natural priority, but right now, to make it tangible, making a “business case” is what you have to do. If you can get results that way, then in ten years it will be a different conversation.’

He wants to start that conversation now. Part of his remit on the BFC’s board is to help steer the diversity journey onwards and upwards. But he’s also personally spearheading an – as yet – top-secret incubator programme that focuses on the operational side of fashion: the future CEOs, HR directors, operation managers and logistical experts. It’s where he sees a huge opportunity for the sector and it’s an aspect of fashion he knows well, partly from Deloitte’s, where he was involved with LVMH’s acquisition of Nicholas Kirkwood, and later when he advised investors in Roksanda, long before he became the company’s CEO in 2018.

‘There is definitely a talent issue on my side of the fashion business,’ he explains. ‘Probably because the British fashion industry is a handful of macro players who are all household names – Burberry, Alexander McQueen, Vivienne Westwood, Paul Smith, Stella McCartney. Everyone else is very small. Where do those smaller businesses tend to find their obvious talent? Within those macro players. But you’ve got these outsiders, like me, who have never seen the fashion industry as a viable career option. We could do with fresh blood and fresh perspectives. After all, resetting after Covid means there’s even greater pressure on ops and finance, but where is that fresh thinking coming from?’

Fresh talent. Movement at the top. Breaking apart the age-old networks that have dominated the fashion industry. Creating role models with different perspectives. These are not the whole answer to shaking up fashion, but they’re a start. And with Jamie Gill leading from the front, it feels doable.

Farah Storr is the head of Writer Partnerships at Substack UK. She is the former editor in chief of ELLE and Cosmopolitan.

Featured image: Jamie Gill (Portrait by Luca Strano)