Yasmin Zaher: ‘Reading Is Liberatory; It Can Transform You’

By

5 months ago

Belinda Bamber chats to the Palestinian author of The Coin

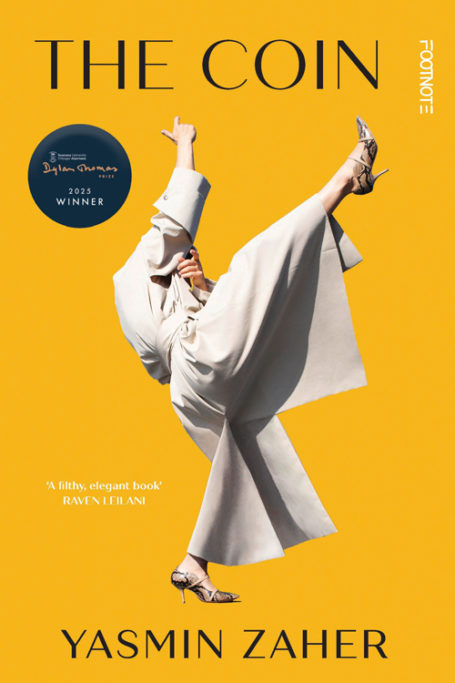

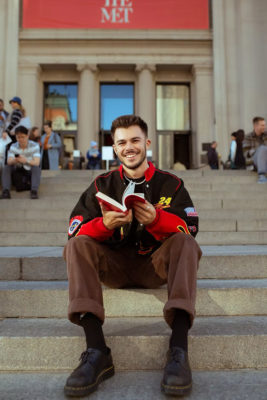

Dylan Thomas prize-winning writer Yasmin Zaher is quickly making a name for herself in the literary world. And with her upcoming event at the Chelsea Arts Festival this September – where she will be in conversation with the internet’s resident librarian Jack Edwards – we can’t wait to see what she will do next. Following the success of her debut novel The Coin, Belinda Bamber chats to the Palestinian writer about literary, political and sexual freedoms.

MORE: 8 Books To Get Back Into Reading

C&TH Book Club: The Coin By Yasmin Zaher

Belinda Bamber: The coin of the title seems to be both a talisman of the narrator’s childhood in Palestine and an emblem of her moneyed lifestyle in NYC. What is its significance for you?

Yasmin Zaher: I like that you thought of the coin as a talisman. The narrator is a wealthy Palestinian woman who moves to NYC in search of reinvention and the American dream. On arrival, she remembers swallowing a coin as a child, and becomes convinced it is still stuck in her body, driving her strange, compulsive behaviour. Gradually, it becomes a symbol of her childhood and trauma, infiltrating all aspects of her new life: love, sex, capital, debt, and her work as a teacher. As I was writing, The Coin metamorphosed into a mystical novel, in that I still find all kinds of riddles and surprises in it.

BB: Why is the narrator obsessed with elaborate cleansing rituals that never quite purify the ‘rot’ of her body beneath her McQueen dress?

YZ: The narrator goes through an existential transformation in the book, especially in the finale. She transforms from a put-together, purified, aesthetic persona to a human being who is moved by their animal nature. I look at who she is at the end of it: she’s mad and uncivilised and unkempt, but she is free of modern nonsense.

BB: She seems generously sweet-natured to her pupils, though her underlying American Psycho traits are a red flag. Did you enjoy developing her anarchic side?

YZ: It’s a pleasure to write an unexpected, somewhat unhinged character. I think it’s fun to read too, but such characters are enacting some of our deepest, most repressed fantasies.

BB: ‘Sasha was the closest person to me, but it wasn’t enough. A comforting diner breakfast wasn’t enough, humour wasn’t enough, what I needed he couldn’t give me.’

What does she need?

YZ: Self-acceptance, I think. The character’s cleaning, grooming and dressing is a form of self-loathing. She’s tired, she wants to be natural. Sasha loves her truly and unconditionally but she cannot receive his love.

BB: ‘In the evening, before dinner, my grandmother would wash my broom while I sat in the swing underneath the grapevine.’ This is a lovely image. How much of The Coin is based on your own life, given your childhood in Palestine?

YZ: Some of the childhood memories in the novel really are my own, especially the memories with the character’s grandmother. This book came from me, from deep places in my mind and soul, from my subconscious, and in that respect it’s a very personal novel. But it’s not biographical. It’s as if my life was the paint and I painted a picture of another life with it.

BB: There are some enjoyably sardonic lines, like: ‘I was scared of American culture. … I don’t mean the right to bear arms, I mean wedding dresses and obesity.’ Would you describe yourself as a satirist?

YZ: Humour is important to me. I don’t know how I managed to write these funny lines in the book; I’m trying to do it again in my second novel and it’s a total failure. I think there is a kind of private freedom in writing your first novel (which I didn’t think anyone would read), that allowed me to take risks and write some outrageous, politically incorrect things. I had fun: it’s a book that is supposed to be fun for the reader too.

BB: Is this vein of humour in any way your defence against political expectations of you as a ‘Palestinian writer’?

There are a lot of expectations on ‘identity’ writers. I didn’t do it consciously but looking back now, I was probably trying to fight my way out the boxes. The Palestinian narrator of this novel is free, rich, sexually liberated, and above all, she’s not a victim, she’s even somewhat of a perpetrator. She’s not that good and moral, and I think there is something humanising about not being perfect.

BB: You’ve said your literary influences include Clarice Lispector, Kurt Vonnegut, Catherine Millet and Michel Houellebecq. Is there a quality that links them?

YZ: They’re all free. This is what interests me most about reading and writing, that it’s liberatory. I remember reading Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions when I was 15. It’s a book with illustrations, and at some point Vonnegut draws a big asterisk and writes something like: ‘Here is a picture of an asshole.’ I wasn’t the same person after that. A year later I read Catherine Millet’s The Sexual Life of Catherine M., where she describes having group sex in the back of a truck. I wasn’t the same woman after that. These are crude examples, but reading really can transform you in a profound way… In my early 20s I read Houellebecq, and I related deeply to characters who had awful thoughts about Arabs like me. It made me more open-minded about people who are at the other end of the political spectrum. In my late 20s I read Lispector contradict herself five times in one paragraph while still making perfect sense. It changed my understanding of subjectivity and reality.

BB: Who is the ‘you’ that you address in the novel?

YZ: The ‘you’ is one of the riddles in the novel, so I will keep the answer to myself. When writing, I try above all to satisfy myself and appeal to my own taste and sensibility. I’m trying to write a book that I would like to read.

BB: The Coin has an almost visceral energy, as though you wrote without constraints. Did it feel like that?

YZ: Yes, my method is to write fast and hard, for an hour or two, so I don’t have the chance to self-inhibit. I also don’t read what I write until days or weeks later. The goal is to suspend self-judgement for as long as possible.

BB: Congratulations on winning this year’s £25,000 Dylan Thomas prize! Were you tempted to dash to Alexander McQueen afterwards?

YZ: Interestingly, I lost all my desire for luxury and fashion in the process of writing this book. It’s as if I purged it out of me. For the years of writing this book I lived, in my imagination, as this glamorous woman who had any piece of clothing, shoes and handbag that she lusted after, and now I’m kind of over it. I think writing this book somehow downgraded my personal style!

BB: How’s life in Paris?

YZ: I live in the Latin Quarter, a student neighbourhood with lots of history and bookshops, near the fancier Saint Germain des Près. It’s chic in a subtle way.

BB: You’re speaking at Chelsea Arts Festival. What do you enjoy about participating in lit fests?

YZ: I love meeting my readers of course. They make me feel seen and I’m very grateful for that.

BB: What are your favourite haunts in London?

YZ: I love this second-hand bookshop in Bloomsbury, called Skoob. I found some of my favourite and most obscure books there. London is also the best city in the West for Arab food.

The Coin by Yasmin Zaher

Bonnier Books, Paperback, £9.99

Yasmin Zaher At The Chelsea Arts Festival

Yasmin Zaher is at Chelsea Arts Festival on 20 September in conversation with internet star Jack Edwards.