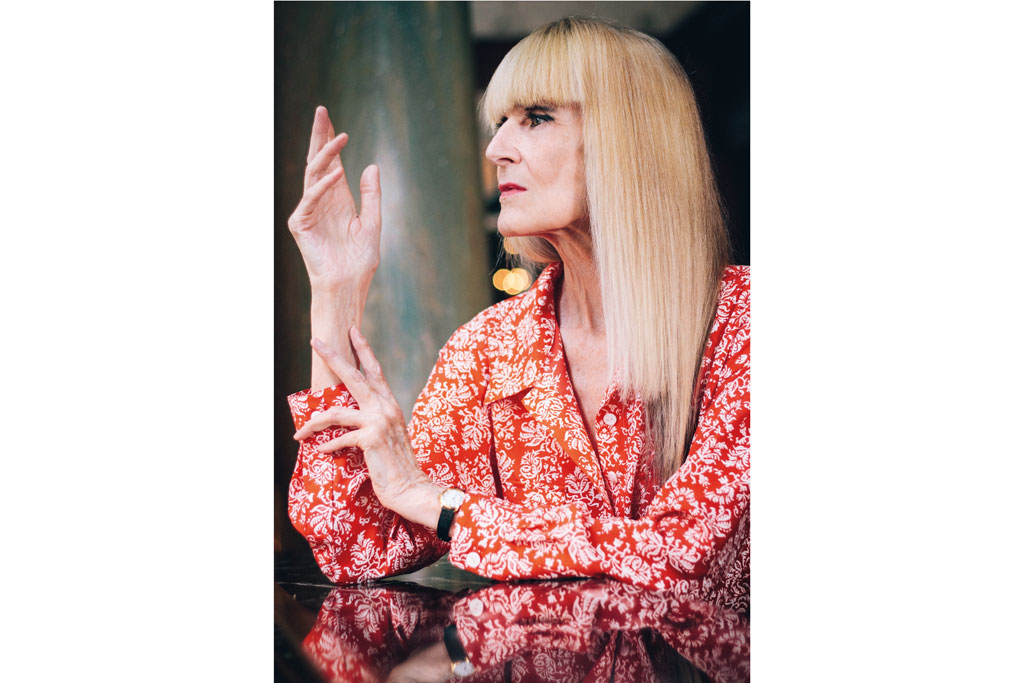

Conversations at Scarfes Bar: Caroline Coon

Charlotte Metcalf meets Caroline Coon

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more

Violence against women and her own abusive childhood have always informed Caroline Coon‘s work. Now she’s getting the recognition she deserves, says Charlotte Metcalf

The Great Offender has finally arrived – punctually for our conversation at Scarfes but late for her deserved place in the established art world. Seventy-four-year-old Caroline Coon has painted every day since she was a child but is only now being recognised as a significant artist. I have known Caroline for over 30 years and seen her figurative, colourfully exuberant, politically overt and sexually explicit canvases be largely ignored. Then last year her friend, the artist Duggie Fields, alerted two gallerists, Martin Green and James Lawler, to Caroline’s work, resulting in her show, The Great Offender, at The Gallery, Liverpool. The Scottish painter Peter Doig, an admirer of her paintings, was so astonished to discover this was her first solo show that he – with Parinaz Mogadassi – is bringing the exhibition to Tramps in London, opening this month to coincide with Frieze.

Why, I ask Caroline, has she caused such offence? She laughs, ‘I never set out to offend but I’ve remained single, earned my own money and decided not to have children. “Respectable” people tend to find this very offensive!’

If you think you’ve heard Caroline’s name before, you have. In 1967, while studying art at Central, she helped organise a demonstration supporting Mick Jagger when he was arrested for smoking marijuana. From there she founded Release, the organisation that, to this day, fights to decriminalise drugs. Her iconic contribution to the 1960’s was recognised in the Victoria and Albert’s 2016 exhibition So You Say You Want a Revolution: Records and Rebels 1966-1970. Caroline is also known for managing The Clash.

Brought up in Kent, she was sent to board at local Legat Ballet School aged five. ‘One day I burst into tears while rehearsing for the Bluebird solo in Sleeping Beauty,’ remembers Caroline. ‘I confessed to Madame Legat that I was being beaten at home. She wrote to my parents asking them to stop. Immediately my parents took me away and sent me to Sadlers Wells in London. Very early I learnt the cost to adults when they intervene to protect children.’

Sadler’s Wells then became The Royal Ballet School, she boarded at White Lodge. ‘I was amongst music, art, costume and theatre design,’ says Caroline, ‘learning about Diaghilev, Nijinsky, Natalia Gonhcarova, Tchaikovsky, Alexander Benois – it was an all-encompassing, holistic, artistic education. My dire, abusive home life contrasted with a nurturing ballet school environment with teachers who loved us.’

From 16, Caroline was supporting herself by waitressing, working in factories and nude ‘glamour’ modelling. She studied at night school for her art A-level and she was accepted at Northampton School of Art. ‘During my foundation course, I was taught classical draughtsmanship by Henry Bird. This gave me the skill to be a figurative painter. My childhood experience within the family was a microcosm of society’s injustice and oppression. My consciousness of feminism emerged as I started to understand the imbalance of power between my parents that led the sadistic displacement onto their children. Decrying violence against women and children became one of the core motifs of my painting.’

As the sixties faded, Caroline changed course. ‘When I saw “Hate and War” emblazoned across the back of Joe Strummer’s boiler suit, I realised that the hippy peace-and-love era was over,’ she says. ‘I began writing about the punk movement. It was my understanding of The Clash and what they represented that enabled me to step in as manager when, like The Sex Pistols, they were breaking up.’

It wasn’t till the 1980’s that Caroline decided to risk painting full time. ‘It was a struggle. My art wasn’t selling. I was broke’, she explains of her decision to become a sex worker. ‘I didn’t ever again want to be diverted from painting daily by having a time consuming “respectable” job.’ She kept a diary, which she published last year as a limited-edition book Laid Bare DIARY 1983-1984. Some of her paintings informed by this experience, The Brothel Series, will be exhibited at Tramps.

‘I have always stood shoulder to shoulder with whores. Until we stop dividing women against each other as virgins or whores there will always be violence against women. To stop such violence, we have to change our sexist culture. My default position is still the beaten child and my life has partly come out of a real Grimm fairy tale. But the violence I suffered as a child has informed my art and the happy ending is: I’m alive to see progressive changes I’ve fought so hard for.’

Caroline’s obdurately ‘offensive’ feminist paintings may still shock, but now that they are appreciated by a globally recognised artist like Peter Doig, they will inevitably be seen by a wider public. About time.

In Brief

Penthouse or Cottage? Penthouse – you can look out over fields that are London’s parks.

Michelin stars or pub? When I was young it was dangerous for women to go to pubs alone so a Michelin-starred restaurant.

Killer heels or brogues? I’ve been wearing Church’s brogues for over 50 years but I’d go insane if I couldn’t wear killer heels occasionally.

Wine or green tea? Wine mixed with water, or a Bellini.

The Great Offender opens at Tramps, 15f Micawber Street, London, N1 7TB on 31 September 2019; www.carolinecoon.com

DISCOVER MORE INTERVIEWS:

Conversations at Scarfes Bar: Nicole Farhi / Conversations at Scarfes Bar: Lynn Barber