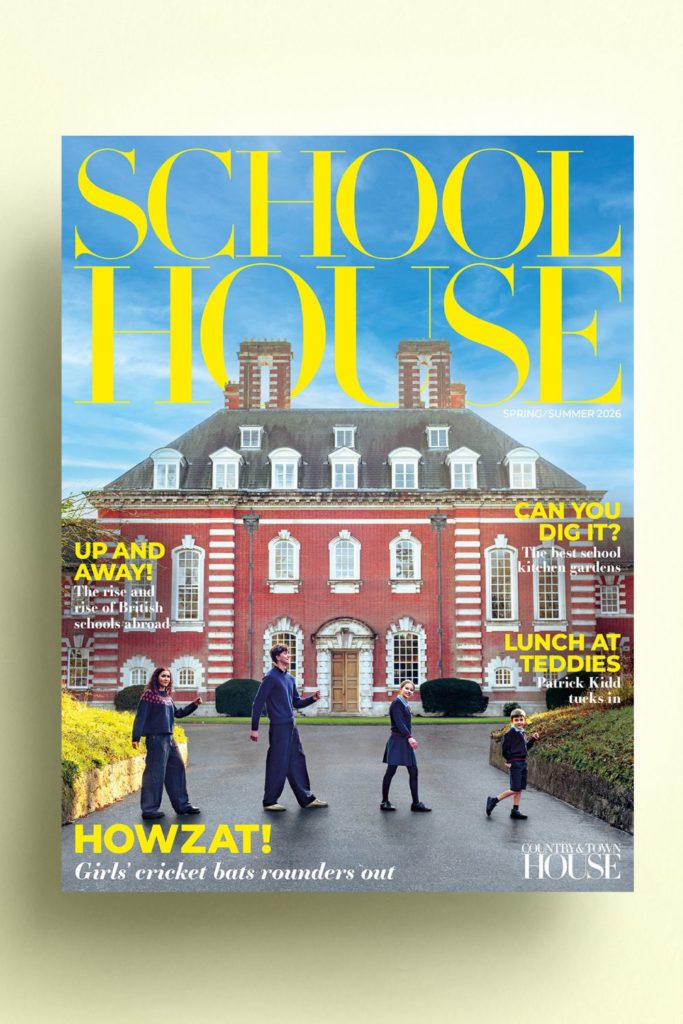

Jane Austen’s Life Is Novel-Worthy Itself: A Timeline

By

6 months ago

Sisterhood, fleeting romance, and tragedy: a timeline of Austen’s life – and how much of her storytelling stemmed from her own experience

Jane Austen is an undisputed literary great whose words have resonated with readers, writers and even world leaders for generations. From the likes of E.M. Forster to J.K. Rowling, from Winston Churchill to Theresa May, or from Keira Knightley to Miranda Hart, Jane Austen has fans in high and varied places. Her books have rarely been out of print since her death over two centuries ago.

This year marks Austen’s 250th birthday, and there’s no better way of celebrating than to explore the writer’s life and works. So how did a clergyman’s daughter from a sleepy village in Hampshire end up as the woman on the ten pound note? It turns out it’s a story that informs much of her own writing, with Austen’s life following the ups and downs of romance, tragedy and high society in Georgian England.

Jane Austen’s Life: A Timeline

Jane Austen (1775-1817) by an unknown artist, based on a portrait by her sister Cassandra

Childhood

Jane Austen was born on 16 December 1775, at the Steventon Rectory in Hampshire. Daughter to Mrs Cassandra Austen and Rev. George Austen, the village’s rector, Jane was the second youngest of eight children. She had six brothers and one sister, also called Cassandra.

Her childhood was largely happy and comfortable, with Jane forming a particularly close bond to her sister – a relationship that would last Jane’s lifetime. While the family were not especially wealthy, they were still a part of the local gentry and so could provide the Austen children with a nurturing environment. A highlight for Jane was access to her father’s extensive library, which provided her with a rich literary education. There are also records of the Austen family putting on theatrical performances at their home, in an interesting similarity with the Brontë set.

By 1783, Jane and her older sister Cassandra were to leave Steventon for Mrs Crawley’s boarding school in Oxford. The school, however, relocated to Southampton in an attempt to escape an Oxford measles outbreak. But in Southampton – a hub for sailors returning home from Gibraltar – the school was hit by Typhoid instead, forcing the girls to return home. In a dangerous twist, Jane contracted the illness and became bed-ridden as her condition worsened. From the very brink of death, Jane was nursed back to life by her mother and sister. Suitably recovered, the sisters then enrolled at the Abbey School in Reading, where they completed their formal education in 1786 and returned home.

Early Writings

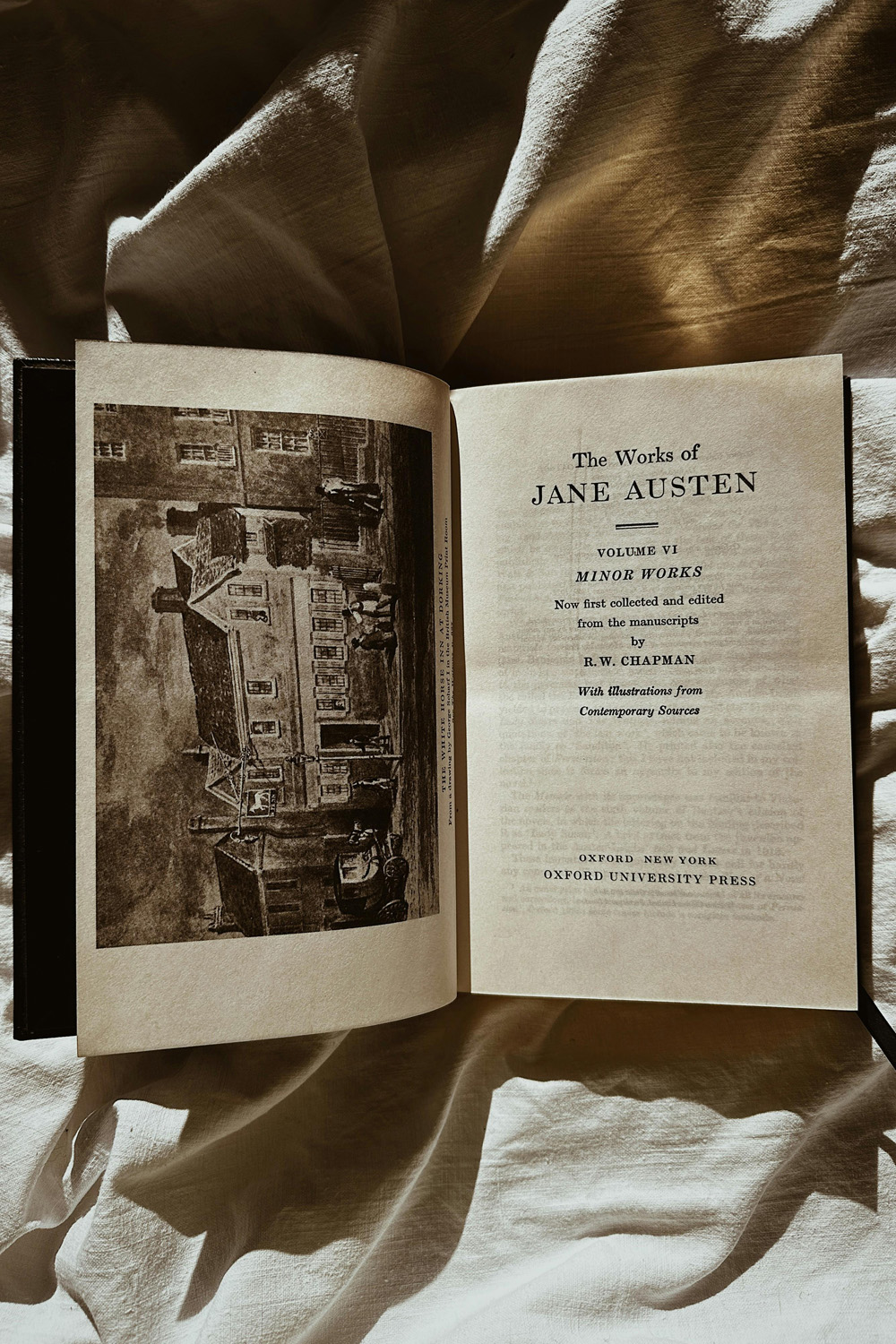

As a teenager, Jane wrote multiple works including Love and Friendship (1790) dedicating it to her exotic cousin, Eliza, who had visited the family, having grown up in India and lost her French husband to the guillotine during the revolution. It is at this point many believe Jane made the conscious decision to pursue writing professionally. In 1795, Jane wrote Elinor and Marianne, a story she would later rework into Sense and Sensibility, her first published novel.

Now, Jane would have her first proper romantic encounter. In December 1795, a young lawyer named Tom Lefroy visited his relatives in Ashe, a village near Steventon. Jane seemingly fell in love with Tom, who was studying to become a barrister in London. The pair danced and rejoiced in each other’s company, as recounted by Jane in letters to her sister. However, in January, Tom was taken back to London after his family deemed a marriage arrangement with Jane to be too impractical, as they both had no money. The experience left Jane heartbroken, and with new insights into the unfairness of marriage.

From 1796, Jane began writing an early draft of Pride and Prejudice, which would later become her most celebrated work. Her father, who had much belief in his daughter, offered the novel to a publisher but it was rejected. Bruised yet undeterred, Jane wrote another piece named Susan which would later become Northanger Abbey.

New Beginnings In Bath

In 1801, Jane’s father, Rev. Austen, unexpectedly retired, uprooting Jane, Cassandra and their mother to take up lodgings in Bath. By this point, the Austen brothers had left home, two becoming naval officers; two becoming clergymen; and one, Edward, being adopted by a richer family – who were distant cousins of the Asutens – and taking the surname Knight. George, the other brother, had severe epilepsy and was possibly deaf and lived apart from the family.

In Bath the following year, ‘romance’ struck again and Jane was surprised by a proposal of marriage from Harris Bigg-Wither, the ‘unattractive’ but rich brother of her childhood friend. In the spur of the moment, Jane accepted for pragmatic reasons – she was getting older and money talks. However, having slept on her decision, the next day Jane changed her mind and declined. It would be the only offer of marriage Jane would ever receive. It seems she followed her own advice that she would later give to her niece, Fanny Knight: ‘Anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without affection’.

By 1803, Jane decided to sell her manuscript of Susan to a publisher for £10, on the advice of her brother Henry, whose lawyer organised the deal. However, the novel was not published, demoralising Jane. Unfortunate events continued in 1805, when Jane’s father suddenly died, leaving the Austen women dependent on the goodwill of the Austen brothers, without any reliable means of income for themselves.

Through Adversity To The Stars

In search of a cheaper cost of living, the sisters and their mother moved to Southampton and then once more to Chawton Cottage, after being offered it rent-free by the elder brother Edward, who had now inherited his adopted parents’ estates, with land in Chawton, Steventon and Kent.

With newfound security, Jane turned her attention back to writing. And to great success. In 1811, Jane published her first novel, Sense and Sensibility. The novel was a hit, with many favourable reviews; the first edition sold out completely, forcing a second edition to be commissioned. The book was published anonymously except for the enticing detail that it was written ‘by a lady’. The novel tracked the lives of the three Dashwood sisters and their widowed mother who had been forced to leave their Sussex estate and move to a modest dwelling owned by a distant relative in Devon. The autobiographical parallels were clear.

Just two years later, Pride and Prejudice was ready for print. Jane was paid £110 for the copyright, and due to a large advertising drive, the novel was an instant success. Then came Mansfield Park, her most political work yet – with the first edition selling out in just six months – and, following that, Jane began Emma. She was on a roll.

By now, Jane’s real identity was somewhat of an open secret among certain, fashionable circles. Indeed rumours had swirled that royalty were among the many readers of Jane’s work. On one of her many visits to London, Jane was invited by the Prince Regent, through his librarian, to view the royal library at Carlton House – an invitation Jane readily accepted. It was there the librarian confirmed to Jane that the future king was a fan and that she ‘was quite at liberty to dedicate’ her next work to the Prince. Amusingly, Jane was initially unsure, finding the Prince’s lavish lifestyle unpalatable, but was convinced by her friends otherwise. And so, when Emma was published in 1816, it was with a royal dedication, the ultimate marker of literary success. Northanger Abbey, with the rights bought back from the publisher who failed to print it, and Persuasion (initially called The Elliots) were finished and next in line for the press.

Cut Down In Her Prime

In a tragic turn of events, Jane fell ill in 1816. Continuing to write, Jane embarked on a new, perhaps more melancholic project, Sanditon. She only completed the first twelve chapters before illness overcame her. By early 1817, Jane was bed-ridden, returning once more to the state of her childhood Typhoid infection. This time, Jane wasn’t so lucky. In April, Jane wrote a short will, leaving almost all her possessions and funds to her ‘dearest sister Cassandra’ and on 18 July 1817, Jane Austen died aged 41 years old at her sister’s lodgings in Winchester.

In December 1817, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion were published posthumously, for the first time revealing Jane Austen as the author. That year, in a bid to safeguard her sister’s reputation, Cassandra burnt the vast majority of her sister’s letters, leaving just 160 of an estimated 3,000. The letters would have been rich in detail of Jane’s life, but no doubt highlighted her sharp tongue and could have painted her in a bad light.

What could have been, if Jane hadn’t been cut down in her prime so cruelly, (or if Cassandra had kept a more expansive record of Jane’s correspondences) surely haunts literary historians and ‘Austenites’ alike. Whether it was cancer, Addison’s disease, arsenic poisoning or lupus that killed her – the debate still rages – the fact remains that Jane led a full life and left behind the richest legacy, having inspired readers with her words for generations – and generations to come.