Review: Hogarth and Europe, Tate Britain

By

3 years ago

Love Bridgerton? Here's the bawdy, brutal side of Georgian Society

Five Reasons to See Hogarth & Europe at Tate Britain

From Netflix’s Bridgerton to Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, you might have come up with a few ideas on 18th Century Georgian society: wisteria-twined houses, empire-line dresses, maybe even a duel. But step into Tate Britain’s Hogarth & Europe and you’ll quickly see the uncomfortable reality that lies beneath the pastel blue veneer. From tackling the gin craze, the transatlantic slave trade, and class, Hogarth and Europe prizes open this period like never before. Here are five reasons we think it’s worth getting out of the house for.

1. Love a G&T? Learn about its grizzly history

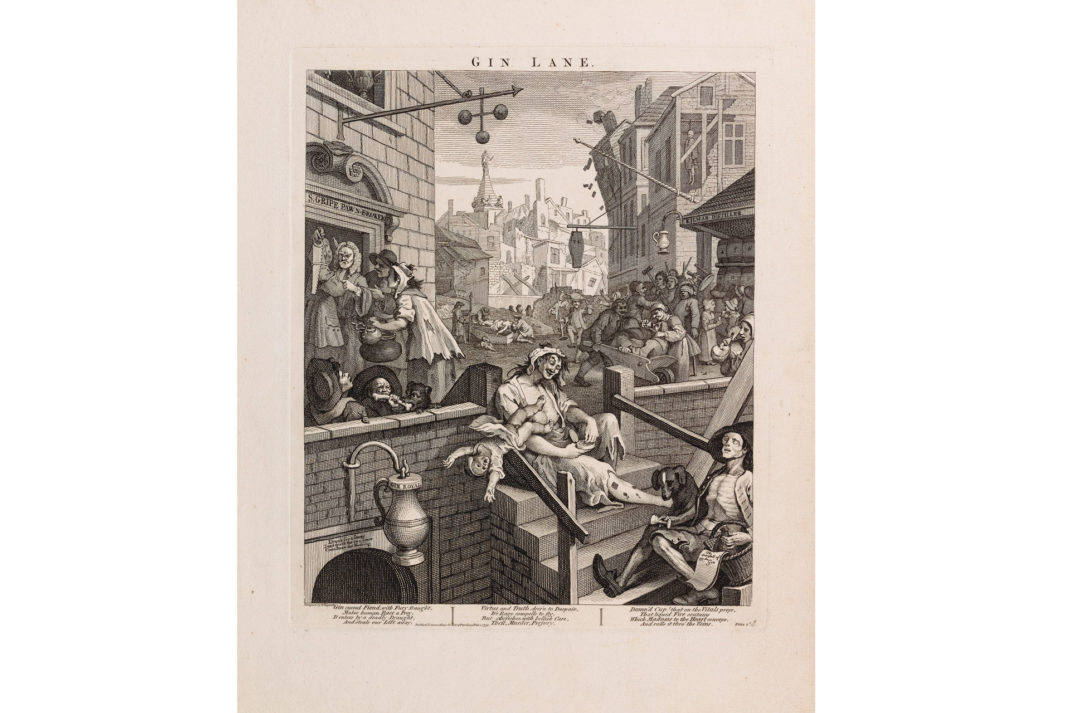

William Hogarth, Gin Lane, 1751, Andrew Edmunds

The 18th Century satirist Sir William Hogarth is best known for his prints on ‘modern moral subjects’ (a subject he pioneered at the time). One of his most famous works is, of course, Gin Lane. The print etches a scene of an urban hellscape: a drunken mother drops her baby off for some snuff; a man fights a dog for a bone; a brawl ensues. 18th Century Britain was then in the throes of the Gin Craze, where large swathes of Brits were drinking two pints of gin a week. Gin Lane was seminal in ushering in the 1751 Gin Act, where gin shops were then greatly reduced.

2. Learn About Britain’s role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Alice Insley, curator of the Hogarth and Europe exhibition put Britain’s leading role in the transatlantic slave trade as a crucial way to understand Hogarth, explaining that, during Hogarth’s life, 1-3% of Londoners actually had African heritage at the time.

Discussing white supremacy and the transatlantic slave trade of the period is an important perspective, and a nice fresh take on some very well-trodden classics. A Rake in Progress, one of Hogarth’s most famous works, traces the downfall of the young man, frittering away his fortune on sex, drink, and gambling. The exhibition used the opportunity of the placard to raise the voice of the African butler-cum-manservant in the scene imagining his take on the pretentious aristocratical household, which was a nice touch.

Though some analysis has mixed success, in a portrait of Hogarth, the chair on which he sits is described to ‘stand-in for all those unnamed black and brown people’ as the timber was sourced from colonies at the time. It’s on these occasions where the analysis seems overly suggestive than factual.

3. …but there is also humour to be found

Instagram starter packs are probably today’s most disseminated form of satire, but it’s interesting to know how we got here. Sir William Hogarth is widely held as being the father of it; mocking his characters by saturating the scene with objects that show their ridiculousness and anxieties. The modern moral subjects: A Rake’s Progress, Marriage A-la-Mode, A Harlot’s Progress are drenched in humourous little scenes that get your eyes darting around the work. It makes a refreshing change where exhibitions can sometimes give a feel of silent intimidation.

4. Peek into 18th Century’s obsession with class

William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête, 1743-45, © The National Gallery, London

Before spending long in the exhibition, you’ll quickly twig that Georgian society felt anxious about class, and how marriage was its ultimate mover and shaker in the game. A must-see in the exhibition is the six-part series Marriage A-la-Mode. Tracing the fatal consequences of marriage for money over love, two self-seeking fathers (one a penniless aristocrat, the other a wealthy merchant) arrange a match that’s destined for disaster. The longer you look at the objects strewn about the room, the secrets unravel.

5. See how the role of the artist changed

William Hogarth, The Painter and his Pug, 1745, Tate

European society was at a time of relative peace after a century of conflict and war. So following a consequent rapid economic growth, luxuries that were usually exclusive to the wealthy now became far more accessible to the burgeoning middle classes. Images lined the shops and markets of cities; theatres were packed. This changed the role of the artist as the demand changed. So instead of being reliant on the Church or a patron, artists could become more self-sustaining, almost like a freelancer, which allowed Hogarth to take on this role as a social commentator, in a way that wouldn’t have been possible before.

FINAL WORD

As much as we love to marvel at the Enlightenment ideas, the architecture, interiors, and binge the period dramas of the 18th Century, Hogarth and Europe grounds our romanticism of the age. The exhibition reveals just how much these ideas and works of art were mainly produced by and benefitted by white men, and gives that context of grittiness that’s often elusive in our contemporary understanding of 18th Century society.

SEE MORE

The Biggest Exhibitions of 2022 / What to Buy: The Best Art Books Ever

Main Image: William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête, 1743-45 © The National Gallery, London