How Is Cornwall Leading The Way On Regenerative Tourism?

By

2 years ago

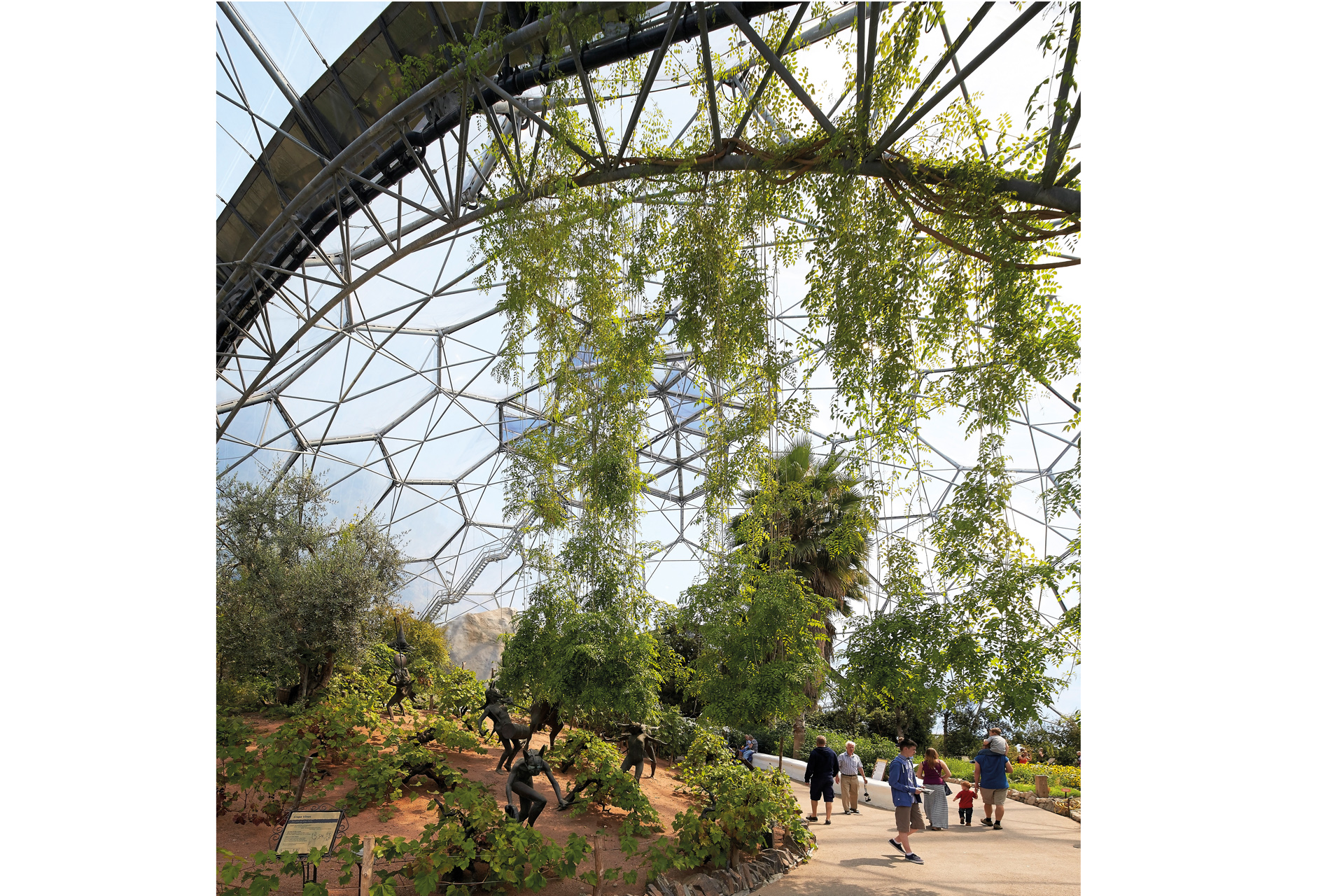

We find out more from founder of The Eden Project, Sir Tim Smit

Cornwall is leading the way on climate action and regenerative tourism, and there’s many things we can learn from the county, writes Rebecca Cox. The county has recently been deemed the greenest place to live in England, according to research from Kia, which cited reasons such as an abundance of eco-friendly hotels, inspiring outdoor spaces, and a high percentage of EV chargers. It’s also home to the Eden Project, a charity and venue dedicated to the natural world. We spoke to its founder Sir Tim Smit about why Cornwall is a leader in environmental change.

Sustainable Things To Do in Cornwall

Searching for Eden: Sir Tim Smit on Regenerative Tourism

‘The word “regenerative” has become very fashionable over the last three years,’ Sir Tim Smit, Executive Vice-Chair and Co-founder of the award-winning Eden Project, tells me. ‘But it is in regenerative farming that one can see the traces of regenerative tourism.’

Regenerative farming is the overhaul of farming practices that favour producing as much as possible as quickly as possible for those that work to restore soil quality, support biodiversity and uphold healthy ecosystems, while also producing higher quality produce. It’s also about taking a ‘bigger picture’ approach to business – not just measuring profits, but impact and longevity. You can see how this concept is inextricably linked to Sir Tim’s work at The Lost Gardens of Heligan and the Eden Project, both in Cornwall, where biodiversity is king and environmental education is at the heart of everything.

In the same way that farming practices are being overhauled, a more holistic attitude is needed for regenerative tourism, too. ‘It’s one thing being more environmentally friendly,’ says Sir Tim.

‘But this means less damage, less waste. That isn’t regenerative – it is just less degenerative. Humans are the only creatures that have waste that can’t be consumed by another part of the food chain.’

The regenerative model means turning our back on ‘make-use-dispose’ ways of consuming and finding a more circular way of living. When it comes to travel, this means we stop simply taking from the land and local communities, and instead ensure we are giving back to them.

A digital render of Eden Project North

Founder and CEO of ocean ambassadors’ organisation NOAH ReGen, Frédéric Degret, tells me: ‘Regenerative tourism seeks to make travel a force for good. It aims to replace the consumptive, extractive and exploitative nature of traditional tourism with a model designed and carefully managed to bring net benefits to destinations and local citizens. It works by insisting that communities and the environment are given the same importance as profit: the so-called triple bottom line principle of people, planet and profit.’

When it comes to the ‘people’ part of this trio, what can we learn from Cornwall, home to many ongoing regenerative projects? The county is leading the way on climate action, working toward a net zero target of 2030, two decades ahead of the rest of the UK. Its green technology agenda includes floating wind power, lithium mining, electric car batteries and geothermal energy.

Sir Tim points to Chris Hines and his work setting up local action group Surfers Against Sewage in 1990 as a tipping point. ‘It became a national institution, but it gave the county a sense of agency. It makes the search for alternatives feel like a shared experience.’ But there is a push for more. At the time of writing, a ‘climate camp’ of Cornish activists is set up outside the county council offices in Truro campaigning for faster action.

Perhaps the key to regenerative tourism is empowering visitors to feel like they can be part of this push for change. Sir Tim says this is already happening in Cornwall: ‘I think that most of the visitors to Cornwall come with the desire to be honorary Cornish people when they are here. They are under the cultural influence to behave as a Cornishman would have them behave.’

This relationship between community and environment is the key to regenerative tourism as a whole. It is perhaps the reason why Cornwall is leaps ahead of much of the UK in this area, with countless regenerative projects, not just at Eden or Heligan, turning into unbeatable visitor experiences. Wellness retreat Cabilla, near Bodmin, is another, as well as Coombeshead Farm, which offers soil-led agrotourism on its 66 acres of land.

©Hufton+Crow

But can this model be replicated elsewhere? Yes, but it won’t be easy, says Sir Tim, and it requires tourists to want more from their experience, too. ‘How can you make tourism a community-wide enterprise?’ he asks. ‘Can you have a series of protocols for tourism, which are like a declaration of the moral direction under which each hotel, bed and breakfast, destination, restaurant operates? As well as in terms of the waste produced and in terms of the commitment to buy off each other in a small area. And the ability to pay people properly.’

Being truly regenerative starts with taking a community-first approach to new tourism projects. ‘We’re building a new Eden Project [in Morecambe in Lancashire],’ says Sir Tim. ‘And we’ve done this incredible community-wide negotiation and conversation. People want to be trained up to have jobs. And, suddenly, you find that you can start talking to a bunch of farmers about forming a cooperative because you’re saying, if you’re a cooperative, we will buy from you.’

And the locals themselves have to be on board. ‘The problem with exclusivity is it does create a rage and people hate when there’s something exclusive in an area where they live. So you have to also create a number of events on a regular basis where the neighbours can use it, see it and enjoy it.’

Tourism destinations putting their communities at the heart of what they do are ensuring a future that is truly sustainable – for both people and planet. This can include limiting access to visitors, or alternatively, ‘creating a heck of a lot of new areas for people to visit,’ says Sir Tim. ‘That’s another way of looking at it. Some of this regenerative tourism is about reimagining the landscape. And getting away from the notion of the honeypot visitor destinations [like Cornwall or the Lake District].’

Above all, it’s about treating the most beautiful corners of our planet with care and investing in the people who already live there, I say. Sir Tim agrees: ‘Beauty is at the heart of all of this – but you know that already.’