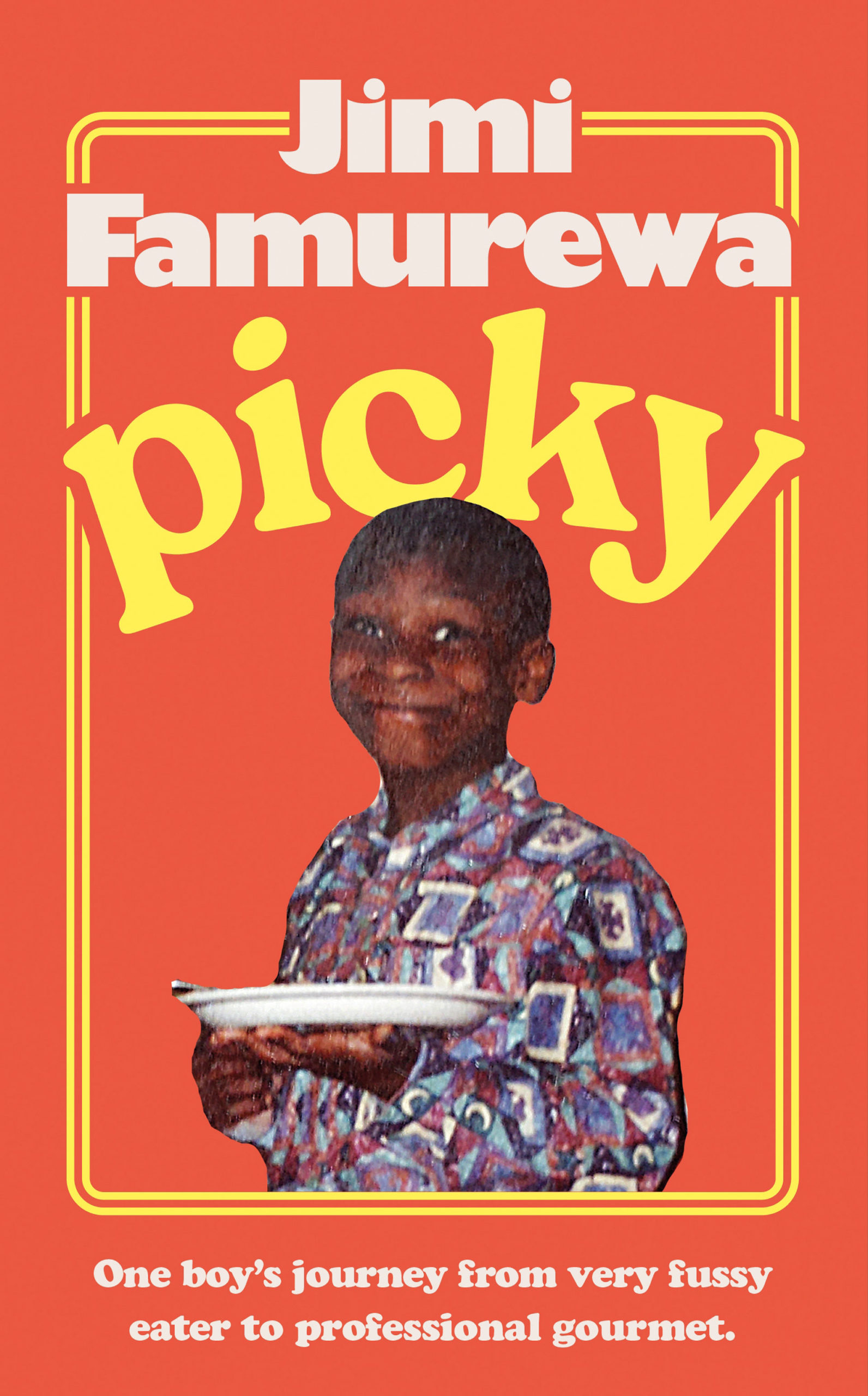

Jimi Famurewa Thinks The Restaurant Critic Still Matters

By

8 months ago

Chewing the fat with food critic Jimi Famurewa

Are critics still relevant in an age of TikTok trends and EatingWithTod? Jimi Famurewa thinks so. Tessa Dunthorne sits down with the food critic and Masterchef judge to chew the fat.

Jimi Famurewa On Writing His Memoir And Why The Food Critic Matters More Than Ever

So, you’ve recently put a book out. How are you feeling about it?

I feel good. It was such a fast pivot from writing it in quite intense solitude to suddenly presenting it to the world and sharing it with other people. I sent the book to a few people – Jamie Oliver, Asma Khan, Ruby Tandoh, Felicity Cloake – and it was quite a nervy moment. I was really gratified that they all came back to sincerely say they enjoyed it. I’ve provided quotes for other people’s books, and I underrated how lovely it would feel to have people articulate things on my work.

Who were you most nervous about reading it?

I was thinking family, but they’d all read it in advance and were so supportive. My mum did a line-by-line response – a lot of ‘that didn’t happen’ or ‘I don’t remember that’. But all in good nature. Thankfully she’s not alerted her legal team yet!

I can imagine writing a memoir’s therapeutic in a way… Or do you need to have a bit of therapy afterwards to deal with the exposure?

Both. To be honest, it was therapeutic to unpack these things. I really ruminate, I store things up, and this book goes all the way back to childhood. But similarly, in Settlers, it’s made up of a lot of things that I’ve just been thinking about and it’s almost a worrybead thing I just turn over in my hand for years and years… So it’s really great to have an outlet and a platform to work things out on the page.

But I think what it’s set in motion might need a little bit more discussion… And therapy. It felt like I had multiple personal breakthroughs.

Tell me more about these breakthroughs.

I suppose I connected how much of a fussy child I was about certain things, and how scared I was of certain foods, for the first time. It’s so fascinating to speak to the number of people who were fussy eaters who now work in food … Like Phil Rosenthal, he talks about how fussy he was growing up… And now he loves basically all food.

I now eat so much enthusiastically and analytically but then I just didn’t have the tools. I didn’t have the language or vocab or agency to say, and a lot of that is cultural, right? I don’t like tomatoes, but maybe I’ve only tasted terrible tomatoes that haven’t been seasoned.

And I think I understood how different chapters of my life – going to university or working as a restaurant critic – gave me the opportunity to be a different person.

Plus another breakthrough, I realised that I have been doing a lot of work to uplift Nigerian food in recent years as a means to reclaim that culture for myself. I always felt like those foods were the possessions of my grownups and they might be inaccessible. Like, I can’t cook these dishes because my mum cooks them so well. So I had to find a way to make my own Jollof rice in more ways than one.

You talk about food in the book almost with the palate as a permissive thing; that you need permission to be told something can be yours or is acceptable, normal.

Yeah, I think that’s totally it. I see it now with my own kids, and we’ll have these debates –just yesterday my youngest was telling me she’d not eat asparagus, and I said, ‘but you’ve never tried it’, and we have these conversations.

I try to be relaxed about it as a parent because a big part, for me, was that when I entered different environments as I went through life, I realised it wasn’t very cool to be fearful and just have the chips. One of the moments I remember in Picky is going to a curry house for the first time with my friends – all white English – and they all ordered curry in that very English way: picking the hottest thing possible. And there’s me, growing up in a spicy dominant house, eating peppery stews since I was little, I had this fearful attitude to curry because it was unfamiliar.

We all have capacity for change. So much of the influence from your environment is just what you’re presented with. You can think of your taste as fixed and all it takes is the right person to offer it and it can completely change your viewpoint.

I definitely feel that I was quite firm in my tastes and my pickiness growing up for a long time. What I really valued and what I really wanted was to be accepted socially and to not be ostracized.

I think that’s hopefully something I acknowledge well in the book – that we should all be open to that capacity to change.

Do you feel like you occupied a palate torn between British and Nigerian foods growing up?

Definitely, massively.

But I think it helped me, in a way. Thinking about it – especially in the light of all these justified conversations about junk food marketing to children – I remember I had friends at that time who might’ve been from anywhere but we were all in thrall of McDonald’s, Wimpy, KFC, Lunchables, and I totally exoticised and romanticised these foods – but I was still eating Nigerian flavours at home. And one of the realisations of Picky was that that diet at home was the thing that probably saved me nutritionally.

My mum was making fresh foods, giving me pulses in the form of stewed beans, and I’m having rice, tomato stews, I’m getting balance here and there. Whereas otherwise – I joke – how did I not have scurvy?

My entire diet was so advertisement influenced. It’s probably true for a lot of kids who grow up with multiple cultures from their parents, because it feels so glamorous. Whereas I never really got that with Nigerian food. There was an ambient idea of how stigmatised cultural foods were.

I remember a Caribbean-heritage girl at my school asked me if it was true I ate bright orange rice at home. And I was so crumpled, thinking ‘I’ve got to bluff this out’, and like I had to make out that it was just chips and ham sandwiches at home. From an early age I think I was conscious of that tussle, and the idea of my food sitting between cultures.

And now you’ve done so much in your career to uplift voices from the African diaspora and representing, in particular, West African food. Do you think it’s likely your kids will have a different experience from you, accessing food as well from Lagos?

I think it will be different. It’s so much more mainstream now – Jollof rice is so well known, and it’s a starkly different cultural environment. Like in the recent Great British Menu, where you’ve got a white South African who lives in Kent and runs a restaurant cooking black West African dishes and curried goat, and that just tells you how far we’ve come.

But I’m always conscious that my kids will have to go on their own journey with it. Their mum is white English, too.

And there’s still a way to go.

Yeah, I was thinking about some of those restaurant lists – how little African representation there is. You’ve got British African restaurants, but not much globally.

Definitely. I think a lot of this is about opportunity, and visibility, and this is a bigger conversation – but it is quite challenging at the moment. There’s a lot of pressure on restaurants like Akoko. I think there is definitely a burgeoning and booming, less fine-dining landscape of black-owned restaurants and food businesses that serve communities, too, but there certainly aren’t enough… And it probably concentrates on the same places.

I sometimes wonder if, if tomorrow I decided to do something else – not being a restaurant critic or broadcaster, someone with power in the food space – there’d be someone else with an experience similar to mine that’d be ready to take up that space. I don’t necessarily know. That’s a challenging thing.

And how do we address that?

It’s about support and platform. A friend of mine was raving about a brilliant Caribbean food popup he’d eaten at a pub, in a kitchen residency in Lewes. And no-one is writing about that. I don’t see reviewers going to those places.

I definitely think that in the last six, seven years it has gotten better in some senses. There’s a lot more onus, for example, on trying to find more interesting stories, different cuisines, and a search for the new. But I also can’t help but notice that every other launch is basically some sort of French bistro, or small plates natural wine thing, and I love those restaurants but it makes you very concerned about the state of the hospitality industry. There’s a focus right now on producing the comforting and the familiar.

Speaking of reviewers and critics… The media landscape is obviously changing. Do you think the food critic is an endangered breed?

Yeah. Again, I think it’s a bit of a mixed picture. I think on one hand, look: print-media, like text-based reviews and content, you’d be mad to suggest that it wasn’t in trouble. You only need look at the number of publications that have closed, are shrinking, or losing budget.

And increasingly people talk about the importance of video, vloggers, people like EatingWithTod or Top Jaw. In terms of restaurant discovery, the figures back up that lots of people now discover restaurants this way, especially in younger generations. People search for things on TikTok and Instagram and it’s the number one trusted voice for many.

But I suppose the counternarrative to that is we look at something like the Financial Times, which has just invested a lot of money into a big relaunch of an expanded food section.

Or Scribehound’s food section, which launched in a really splashy way, as a kind of newsletter based form.

And Substack is running food events.

I think it’s mixed. What I’m encouraged by is that people that are serious restaurant enthusiasts and people in the food industry, like restaurant owners, they all still value a written review from a critic. I think that a review still has the capacity to have a huge impact on trade, business and trust.

More broadly, I keep quoting this fascinating FT column by Janan Ganesh that he wrote in the wake of the Michelin star awards and he made the point that… Even if we’re operating in an era where the role of the critic or cultural arbiter should be in decline, and citizen-journalism plus TikTok vloggers are king… He makes the point that these awards, these standards have never been more important. That while digital platforms make legacy media look sort of prehistoric, they’re still quoting these kinds of accolades. They’ll say this restaurant has a Michelin star. People want guardrails, they want a barometer. The Ballon d’Or, the Booker Prize, the Grammys have never been more important. I think because we’re confronted by so much.

And this definitely applies with food. There’s real value placed in trusted voices and authorities, and so I think it’s not all doom and gloom for restaurant critics. But it’s definitely changing before our eyes, and the power they once wielded is diminished in a lot of ways. I’m clinging to the fact that text can still have such value; so many social media stars, they still want to release a cookbook, it’s still the pinnacle for them. There remains a reverence for the written word.

Picky is out now, £20. uk.bookshop.org