Poetry Has Found A New Audience On Social Media. You Shouldn’t Sneer

By

5 months ago

The medium perfectly suits the art form – and Gen Z are loving it

Though some may sneer, today’s poetry lives on Instagram. Leading the charge is Rupi Kaur, whose collection milk and honey was chart-busting at its 2014 release after beginning life on the social platform. In 2023, Nielsen BookScan reported poetry sales across the world had reached an all-time high of £14.4m, with younger audiences in particular driving these sales – inspired, BookScan claimed, by so-called Instapoets.

This interview is part of our Chelsea Arts Festival Coverage

British poetry anthologist Allie Esiri (A Poem for Every Day of the Year) has now sold over 500,000 copies of her poetry books (and counting), and is no stranger to the golden touch of technology – it was the iPad that brokered her entry into the genre. ‘I was an actor, had just turned 30 and realised I didn’t want to do that anymore,’ she says, ‘and poetry had always been my private passion.’ Apple’s flagship tablet had just surfaced. ‘I realised poetry worked perfectly for the iPad. It could fit on the page; you could press a button to hear a well-known actor bring it to life, or another to record yourself reading it.’ It was the success of these apps that led to publishers approaching her for the book deals that eventually segued into wildly popular live readings at venues like the National Theatre, featuring performers such as Sophie Turner and Luke Thompson.

View this post on Instagram

‘Most poetry, until recently, was written to be read aloud,’ says Esiri. ‘If you were to take it back to Sappho, a balladeer would’ve sung it in the market square.’ And so it is, in a way, a homecoming for poetry to enter the medium of vertical video.

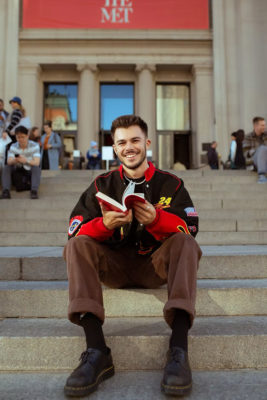

Among poetry’s new balladeers is 29-year-old Lucas Jones, an actor-turned-poet hailing from Cambridgeshire, who has amassed over half a million followers across TikTok and Instagram; 56 percent them are under 35.

He’s an atypical poet – if one is making that judgement on the basis of the voices represented by the national curriculum. He speaks plainly and he did not make his way into the genre via journal submissions. He might have Byronic good looks, but there’s no fusty academic squabble to the words he writes and performs on Instagram and TikTok.

This millennial poet began making videos in part because – on producing his debut collection – he ‘didn’t get a look in’ with the legacy publishing houses.

‘There used to be a certain type of person who was allowed access to literary spaces,’ says Jones. This perceived barrier perhaps turned off younger people, too, from enjoying the work. ‘I couldn’t access it [at school],’ he says; ‘It felt like it was all in this old tongue, and I couldn’t get into the metra or rhythm.’ It was a teacher who introduced him to the work of current poet laureate Simon Armitage, which changed everything. ‘Even if I didn’t understand the exact context, it was in my language. It didn’t have to sound like a “poem”, you can speak as you speak.’

Jones believes social media is a means of democratising access to poetry, both for writers and hobbyists. And, yes, there’s an algorithm that baits sensationalist introductions (‘every artist hates it – trying to generate fucking clicks’), but perhaps this algorithm introduces a certain meritocracy. ‘In the future, maybe people will look back at this time as a renaissance period where you could self-generate, print 100 books and build a life on it. Or be an actor, make films, have podcasts, do all these multi-hyphenate things. You could get your phone out and just make it. I imagine people will find that really attractive.’

Both Jones and Esiri also argue that younger people are today turning to poetry for political reasons. ‘I notice there’s increased viral demand for poetry in troubled times,’ says Esiri. ‘After 9/11, during Covid, in response to dreadful wars… maybe these poems help you feel less alone. The greatest poets of all time express things in extreme circumstances better than most of us can.’

Not necessarily, she notes, to enact tangible change. ‘They’re not going to stop a war or solve anything,’ says Esiri, ‘but maybe these poems help you understand, feel less alone. Some of the greatest poets of all time manage to express things in extreme circumstances better than most of us can express it, and it can be very gratifying that someone’s just put it so well.’

‘All great writing can change minds and hearts. I suppose if people start to think or question things, it can lead them to make change,’ says Esiri.

View this post on Instagram

Jones, in a similar vein, views his role as a sort of caretaker for the next generation. ‘There’s all the Andrew Tate, Bonnie Blue stuff – these extreme symbols of sex and masculinity. I feel some responsibility to counter that.’ His poem I will teach my boys to be dangerous men imagines raising sons who view patience as a strength in the place of bravado and is his most viral video to date.

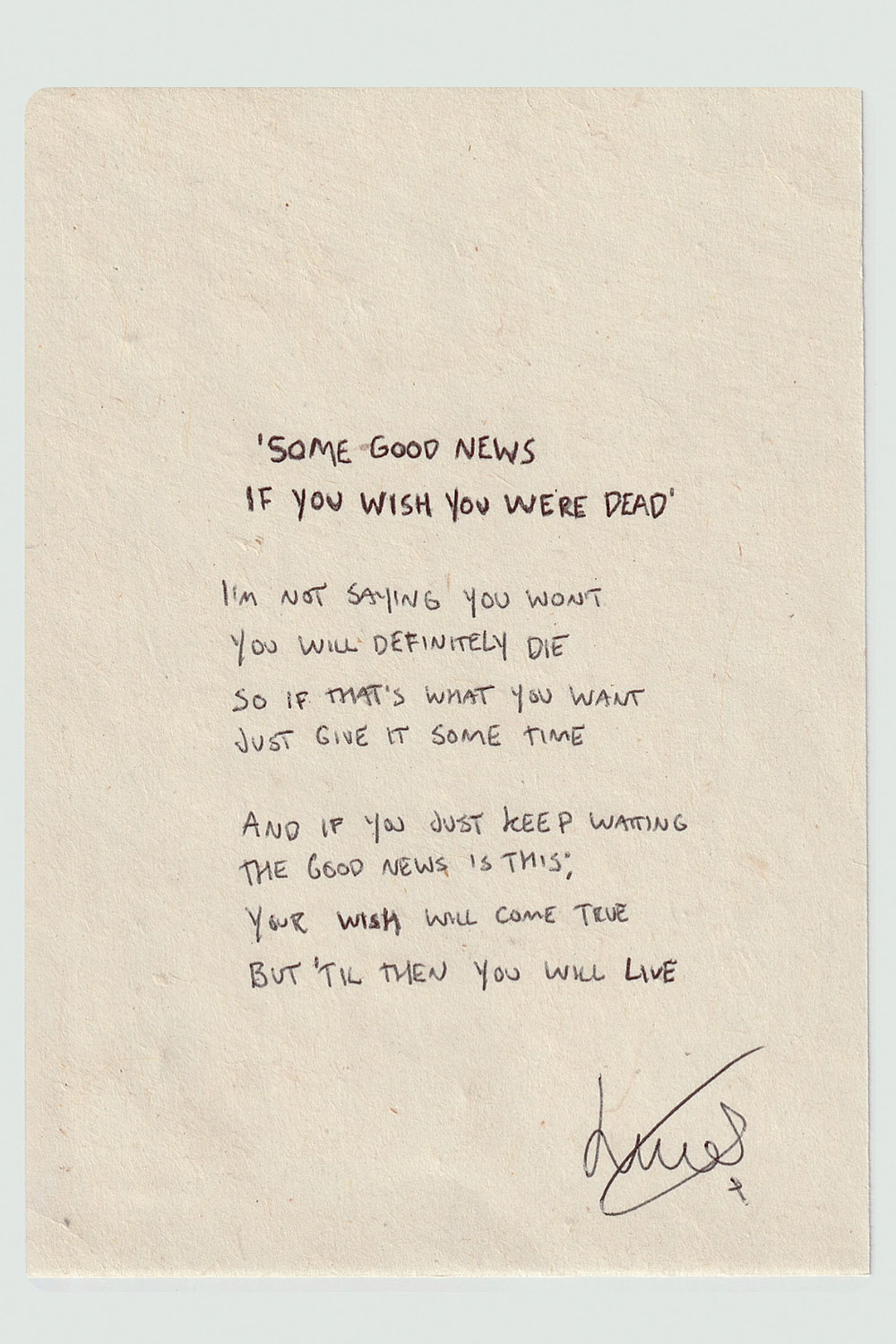

Jones’ work – and those poems that perform the best online – tend towards a hopeful outlook, despite heavy themes or topics. This is possibly the appeal. ‘Without optimism, we’re done,’ he says. ‘I once received a message from a man who had been about to jump from a bridge. He opened his phone to wait for cars to go past, to look normal, and my reel popped up. He told me he’d seen my poem Some Good News If You Wish You Were Dead and messaged me the day after, feeling a bit better. When you hear something like that, it’s a deep reminder of how the genre might reach people.

‘I think if you’re really honest in front of people, it can lead to a chain reaction that changes things.’

See Lucas Jones & Allie Esiri Live

Catch Lucas Jones (19 September) and Allie Esiri (20 September) at Chelsea Arts Festival, with poems read by a cast including Susan Wokoma, David Morrissey and Lesley Sharp.