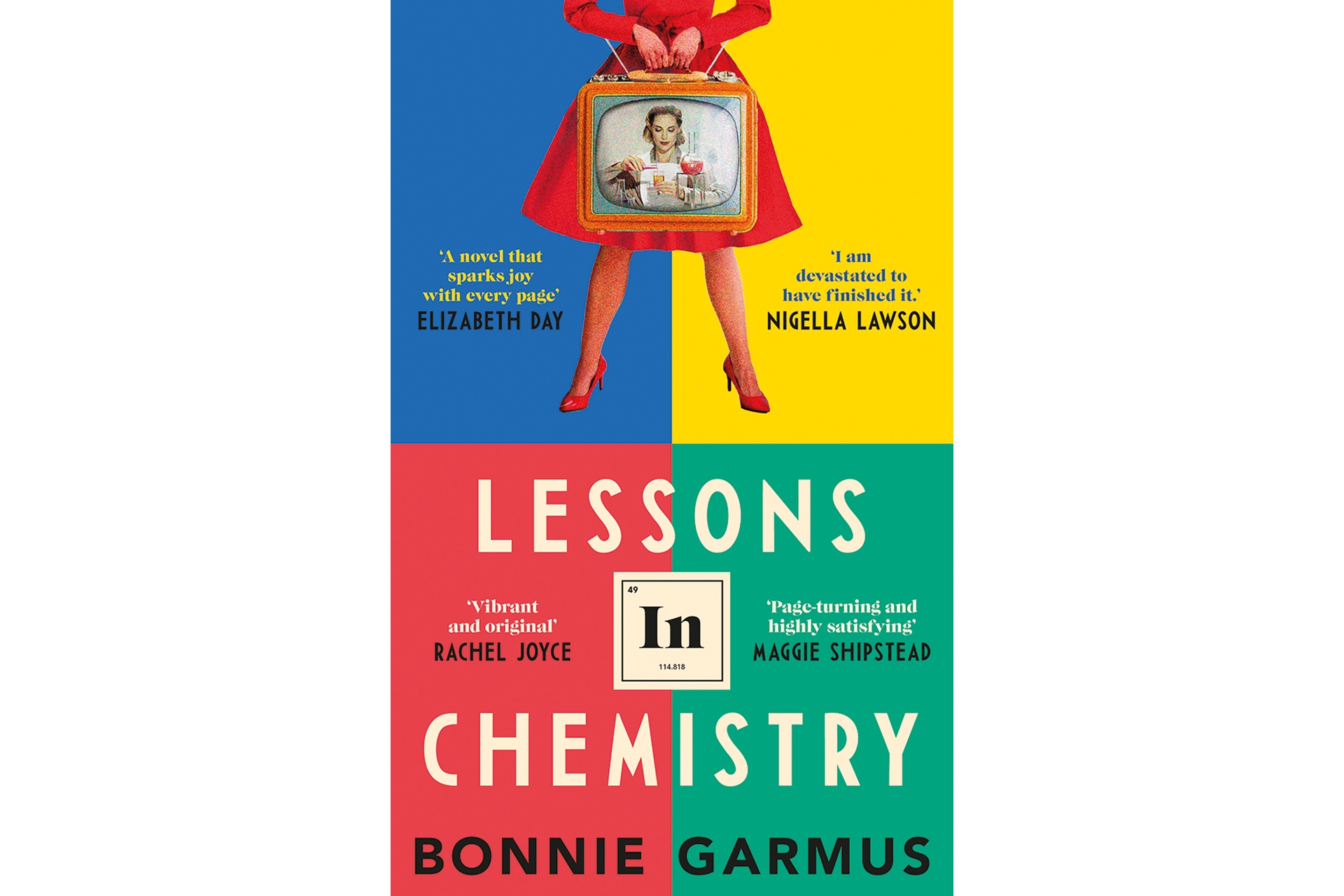

C&TH Book Club: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus

By

2 years ago

Fifties feminism, female heroines and writing frustration

Lessons in Chemistry has been scooped up by Apple TV+ and is being transformed into a new limited series – starring Brie Larson, Lewis Pullman and Aja Naomi King – set to debut sometime in 2023. Last year, Belinda Bamber sat down with author Bonnie Garmus as she explained the fascinating background of her acclaimed debut novel.

Main image by Serena Bolton.

C&TH Book Club: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus

Originally published in May 2022.

Interview: Bonnie Garmus on Lessons In Chemistry

Belinda Bamber: The 1960s setting gave you licence to expose some deplorable misogyny in the workplace. Was that an itch you really wanted to scratch – but had to put in a different time zone so you could give the guys a darned good kicking without needing to acknowledge the changes made since then? How much has actually changed in the science lab in 2022, in terms of respect for women’s scientific practice and research? Is the scientific world ahead or behind the world at large in terms of equality and diversity?

Bonnie Garmus: I set Lessons in Chemistry in the early 1960s because that’s when my mom was a housewife. I did a lot of research to find out what kind of hurdles women faced back then, and it really did shock me. I’d had no idea that pregnancy was considered a fireable offence; that women couldn’t write a cheque unless it was co-signed by their husbands; that a housewife had no legal right to her husband’s pay cheque. Then throw in the fact that very few women were encouraged to study science, let alone become a scientist. Society said women belonged in the home – and that’s where they were stayed – whether they wanted to or not.

Fast forward to 2022, and it’s clear things have changed for the better. But how much better? Today, according to UNESCO, only about 30 percent of the STEM workforce is female. And that’s a problem, not only because STEM careers are far more lucrative than other disciplines (which means women continue to earn less worldwide overall), but because women continue to be under-represented in fields that very much define their futures – women’s health; computer technology; engineering. And although they’ve made inroads, women in these fields – really all fields – continue to face sexual bias. So I set the book in the early Sixties, in part to salute those overlooked housewives, but also to show that those women set a course for the rest of us – they raised a generation of feminists. We just need to keep going. Change is always possible.

BB: You have a distinctive authorial voice. How did your experience as a copywriter feed into that? Was it a difficult transition into fiction? And why did it take a while for you to publish a novel? Was that always an ambition?

BG: I’ve always wanted to write novels. I wrote my first at age five; it was terrible. I wrote another at age twelve; pretty sure that was terrible, too. I liked copywriting because it gave me a chance to write every day while earning a living, but I never stopped wanting to write novels. Still, working full-time and raising kids and rowing and life in general – I had very little extra time. I applied to an MFA program and got in, but about halfway through, personal circumstances forced me to set both that program and the novel aside. I didn’t write for a few years, except at work. Finally, I picked myself up and got back into fiction. I wrote an entirely different novel which I still love but it was very long and was rejected by ninety-eight agents. I don’t think a single person, minus one, read any of it. So I had to pick myself up again. The result is Lessons in Chemistry.

As for my copywriting career, you know how people always say, ‘write what you know’? In copywriting you never write what you know. I loved that; I loved learning new things all the time. And because copywriting is always about putting yourself in someone else’s shoes, you gain a lot of insight into what makes people tick – which is great for character development. Plus, copywriting is all about tone, voice, authority, entertainment. You can’t bore people. I won’t pretend I loved every aspect of that career, but it really did hone my writing, and I was able to bring those skills into my novel. So many great writers were copywriters first – James Patterson, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Joseph Heller, Salman Rushdie, even Helen Gurley Brown. I’m proud to be in their company.

BB: Elizabeth Zott is unusual as a female heroine in that she’s not crippled with the usual female self-doubts (am I pretty enough? Is my bum too big in this?) but has a no-nonsense, head-girl clarity combined with a firm moral compass. Her narrative arc isn’t the usual self-discovery, but rather her growing courage and determination to fight for what she believes in. She’s a feminist who proves herself through action. She steps up. Did you have a role model, or models, for her? And do you think her refreshing clarity and self-reliance – reflected in the clarity of your writing style – benefit from your own wisdom and maturity as a writer? (Hurrah for both those qualities.)

BG: I love this question – thank you. I didn’t have a role model for Elizabeth Zott. She sprang from my own desire to have someone to look up to – someone with integrity; a woman who didn’t waste time doubting herself, weighing herself, apologizing, or smiling nonstop. There’s not a single time in Lessons in Chemistry where you’ll see Elizabeth Zott worrying about her hair, wondering if her skirt will fit, dieting, or rubbing her feet because they hurt from heels. She’s sensible, rational, smart. I made her beautiful for a reason: because I wanted that beauty to be an additional burden for her. Beautiful women, especially back then, weren’t taken seriously – and she is a very serious woman.

As for the clarity, I do think that came from copywriting. If you want to write well, you have to read a lot, but you also have to write a lot – meaning you have to practice. I was lucky enough to have a job that let me do that. In terms of maturity though, I’m still trying to find mine.

BB: Supper at Six is hilarious and a great idea for a show. I was agape at the chemical ingredients given for each dish – were you top in chemistry at school? Do you like to cook? And at table do you say ‘pass the salt’ or ‘pass the sodium chloride’?

BG: I’m not a scientist and the last time I took chemistry was as a teenager. So when I started working on Lessons in Chemistry, I bought a chemistry textbook from the 1950s and taught myself the basics. It was important to work from a 1950s textbook so I wouldn’t inadvertently stray into scientific anachronisms. And yet I still did! Several times, I came up with what I thought was some great chemical metaphor only to find one step of the interaction hadn’t been discovered until 1992 – so out it went. Once I’d finished, I asked two PhD scientists (both women; one is a working chemist) to check the book for accuracy. I slept a lot better after their review. But if any mistakes remain, they’re all mine.

As for cooking, believe it or not, I don’t really like to cook! But I do love and appreciate those who do cook well. Like Elizabeth, I think of cooking as both an art and a science and I’m lucky to have a husband who does it well. As for passing the sodium chloride, I do say that every so often–especially on those days when I find myself missing Elizabeth Zott. She and I spent years together! I always love reconnecting with her.

BB: At age five, Madeline is already reading Dickens and Nabokov (unlike her teacher). More than a child genius, she has the wisdom, observational powers and calm attitude of someone who’s lived ten times as much. (I love that her given name is Mad – one of many delightful quirks of wordplay in Lessons in Chemistry.) Where did this character spring from?

BG: I wanted Mad to reflect a child raised without societal limits – someone unbound by age-appropriate reading and endless rules. Because Elizabeth has long been a misfit and knows the pitfalls, she doesn’t want the same for her child. So she sends her to school, assuming that a school environment will not only provide advanced educational opportunities, but supply that magic ingredient that will save Mad from a life of loneliness – socialisation. Except, of course, it doesn’t.

And that is why Mad’s relationship with Six-Thirty is so important. He initiates communication with her while she’s still in the womb and as she grows, their ability to speak to each other – to communicate at a different level–becomes even more heightened. He calls her ‘creature’ which to humans can sound derogatory. But Six-Thirty is nothing but careful when it comes to words. Calling her ‘creature’ is a compliment; it means she’s more than human. Her wisdom and observational powers come from him.

BB: Which novelists do you admire and learn from? Which three novels would you take to a desert island? (For joy and succour rather than how to build a shelter from coconut leaves, I mean.)

BG: Ha! I’m so grateful to the craft and prodigious story-telling talents of so many, but for me, John Irving’s Cider House Rules, Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, and Kazuo Isiguro’s Remains of the Day would definitely be the books I’d want to be stranded with. But as luck would have it, Roald Dahl’s Matilda, William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, and J.K. Rowling’s entire Harry Potter collection would also wash up on shore.

BB: What resources do you have for stepping positively into the day, when depressing news about war and the environment makes us all long to hide under the bedcovers indefinitely?

BG: It’s so tough out there: war, pandemics, climate change – none of which is remotely funny. But that’s why we can’t lose hope, why we can’t give up, why we need to laugh more than ever – because we can’t let the darkness win. So when I get up, I drink a huge cup of coffee and start work. I want to write stories that remind us of the good in world, that for every Putin, there are ten Nelson Mandelas and Greta Thunbergs. We can solve our problems – I really believe that. But part of that process is finding a way to laugh at our shared failings.

BB: The passionate love affair between Elizabeth and geeky Calvin is a delight to read. Yet it’s clear their happiness triggers jealousy and bad feeling among their co-workers. For a reader, that’s an interesting compound of optimism and pessimism… when you look at humanity today, is your glass half-full or half-empty?

BG: I’m half-full. Life becomes a lot harder if I only dwell on the negatives. But one of the themes I wanted to explore in Lessons in Chemistry was how assumptions are fuelled by what we think we see rather than what we know (the old ‘appearances can be deceiving’ thing). Deception – lying – is one of the underlying themes of the book. Making assumptions about people without actually knowing what’s true happens all the time. For the jealous person, it’s a form of self-deception.

BB: Six-Thirty was my total crush in this story. He’s the quiet hero holding the centre, like Mr Knightley. Is there scientific evidence for a dog learning so many words? (I’m guessing not, and I don’t care, just checking!) Are there any fellow-canines in the literary canon (in any language) he’d shake a paw with?

BG: I’m so glad when readers tell me they love Six-Thirty! And here’s the good news: there is scientific evidence regarding dogs and vocabulary, including a dog named Chaser, a border collie, who actually knew more words than Six-Thirty. (Don’t tell Six-Thirty!). But Chaser wasn’t the inspiration for Six-Thirty, my (now deceased) dog, Friday was. Before she joined our family, Friday had been badly abused and we worried that she might not be able to overcome her past trauma. But she did, and in the process showed us what she could really do, including learning words and sentences that continually surprised us. My favourite: ‘where are my keys?’ (She’d run off and search the usual places – pockets, bags, etc.) When we were transferred abroad, she even learned some German. In general humans tend to underestimate animals – and since of the book’s themes is underestimation, a thinking dog fit right in.

BB: What’s with the numbers when you name dogs? Not only the delightful Six-Thirty, but also I believe your own dog is called 99?

BG: 99’s name comes from an old childhood TV show – Get Smart – which, back in the mid-‘60s, my best friend and I never missed. We started calling each other 86 and 99 when we were eight years old and never stopped, not even into adulthood! But about ten years ago, my friend died unexpectedly, and I found the loss difficult to bear. So when our retired greyhound racer came into our lives, I named her 99. I’m so happy not to have not buried the name along with my friend – and I think she would have approved. As for Six-Thirty, I love how he gets his name through misunderstand, but goes on to use that naming convention to heighten the book’s themes of belonging and family.

BB: Can you please give me an insight into your writing day? When, where, how?

BG: I get up early, drink an enormous cup of coffee, re-read what I did the previous day, then start editing before moving onto anything new. Revisiting the previous day’s work helps me see where I might be going wrong (or right) and helps reconnect me with the voice. I work most of the day, but I always make time for a long walk with 99, the NYT Spelling Bee, and eventually the gym.

BB: How do you organise your bookshelves? And which novel would you pluck out to gift a young woman starting at the bottom of the career ladder today?

BG: My husband is the one who organises our bookshelves and although I’ve never been able to put my finger on why his method makes so much sense, I finally asked him (because you asked me!). Here’s his answer: he shelves books together that, in real life, he thinks would be friends. (I love that.) As for the book I’d recommend for a young woman starting at the bottom – is it wrong to suggest Lessons in Chemistry? (It is.) So I’d also add: anything by Jane Austen. Reading historical fiction has a way of reminding us that our problems aren’t new, and we can overcome them.

BB: What’s the greatest lesson life has taught you?

BG: Don’t give up on yourself. Frustration, anxiety, depression – these are all normal parts of life, and any of them is enough to send anyone into a tailspin. If that happens to you, take a break. An hour, a week, a year – whatever it is – don’t worry. A break isn’t quitting – it’s refuelling. Then recommit.

Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus. penguin.co.uk