Olga Ravn On Witch Trials & Her New Book The Wax Child

By

3 months ago

Belinda Bamber chats to Olga Ravn about witchcraft, historical novels and gender politics

In The Wax Child, Olga Ravn fictionalises the true story of how an unmarried, penniless and childless noblewoman called Christenze Kruckow was put on trial as a witch in seventeenth-century Denmark. It is narrated by a traditional wax doll she has made and carries with her like a live baby – partly, it appears, for help in casting spells. When Christenze is accused of causing the multiple miscarriages of her mistress, Anne, she finds refuge among a group of women in another town, with whom she shares gossip, work, stories and – with Maren – her bed. Is this really a coven of witches, or are they the victims of misogyny, suspicion, and the king’s attempt to divide and rule? This startling, original and beautifully written novel invites us to rethink our ideas about how history is told and what witchcraft really means.

C&TH Book Club: The Wax Child By Olga Ravn

Belinda Bamber: Did you feel like a witch or sorcerer yourself while you were conjuring this fictional story from the real-life witch trials of 1617?

Olga Ravn: I feel like a witch every day. Long before starting this book, I’d scoured archives for manuscripts about magic and folklore. As I studied these documents, I recreated recipes and spells, to try and understand them better. In this folk magic archive I encountered a whole cosmology and worldview with an amazing literary tradition: a distinct voice and way of using rhyme and rhythm.

With The Wax Child I wanted to write in a language that was in dialogue with this specific ‘folk magic tone’: to write the whole novel as one long spell that would put the reader into a kind of trance and leave them, hopefully, transformed.

BB: Why did you write the story from the point of view of the wax child?

OR: In my research, I came across hundreds of witch trials, and in the Aalborg case, I noticed that a key piece of evidence was the creation of this wax doll. And I do have a thing for non-human narrators, which I’ve also worked on in my novel The Employees. This idea that things can talk if you listen. So, one day I thought, what if this wax doll used an ‘I’? And then I wrote the first two pages, which became the opening pages of the novel, and immediately knew this was my doorway. Now I could write about them.

I actually thought for a really long time that I could never write a novel about the witch trials. I’ve done all sorts of other things about witches: radio, visual art, performance, theatre. The reason I didn’t think I could write a novel is probably that I actually hate historical novels. I simply don’t believe we can imagine the internal lives of people who lived so long ago: we will always see them through the veil of our own time.

I wanted to make the distance between now and then very concrete and so I used the voice of the wax child-narrator as a way to instill this uncertainty about the past. The wax child becomes a kind of portal or remembrance-object through which we can glimpse the story of these women in Aalborg. In that way, The Wax Child is almost an anti-historical novel, because it keeps asking: how do we understand history, how, how? I wanted to write a book where this question is never answered, but where the agony of the longing implied in the questions is everywhere.

BB: Why was the newly formed wax child taken to the pastor to be christened at dead of night, as though it was a real infant?

OR: That’s part of the real magical ritual of making a wax child! And it was part of the information that came out during the interrogations of the women in the court case. I have no way of knowing whether these christenings really happened in practice, but you’ll meet this story about a wax child in many, many places.

A wax child or et voksbarn as it’s called in Danish, is a sort of European version of the voodoo-doll. It’s based on this idea called the ‘teaching of signatures’, where you believe an object can have power over what it resembles. Everyone does this magic all the time, it’s like when we go to communion and believe the wine turns into blood.

BB: We’re told in the first line of the book that Christenze gave the wax child ‘hair and fingernail parings from the person who is to suffer’. So we know a deliberate spell is afoot, even though Christenze later claims she’s completely innocent. Why was it important for you to preserve a sense of mystery and uncertainty about whether witchcraft was being practised, or whether this was just a group of women doing what they could to survive in a tough world?

OR: I wanted the reader to ask themselves: What is witchcraft? Where is the witchcraft? What is criminalised? To be confronted with their own, perhaps un-realised, fears of witchcraft and magic. So that each time someone in the book does something a little witchy, the reader will have to ask themselves: Does THIS make her a witch? When do the women of the novel turn into witches? That’s one of the questions I wanted to leave with the reader. I wanted this to mirror the uncertainty of the period, where people were not exactly sure themselves what was witchcraft and what wasn’t.

I also wanted to be loyal to the people of the time who did not have this black and white perspective on magic. A lot of common traditions were suddenly criminalised as witchcraft in Denmark-Norway in 1617. Imagine if, in 2025, it was suddenly forbidden to blow on a child’s grazed knee to make them feel better. In my opinion plenty of people today are having to deal with these sudden and violent mentality shifts initiated by the state.

BB: In insecure political times there’s often a need to blame and outlaw a particular group of people. Who are the witches of today?

OR: The King of Denmark wanted to centralise his power and used the accusation of witchcraft to do so. Such accusations are a legal tool still used by the authorities to spread suspicion and to discipline citizens – very effective when you want to shape an entire population in a particular fashion. Such laws also show us what the powers-that-be think makes a good citizen, a good person. I think racism and classism facilitated through legislation today are examples of that, but I also think of trans people, perhaps especially in the UK, where it is clear to me that legislation affecting trans people tries to define where the line is between men and women, and so what a man and a woman even is. It’s a perpetuation of the gender binary, which is always a perpetuation of the nuclear family. And the nuclear family is one of the most important building blocks of a nation’s economy. To me, upholding traditional gender roles is a way to secure the GDP. Which is also a way you could understand the accusation of witchcraft.

BB: Christenze wrongly believes her high birth will save her from punishment. How, in the seventeenth century, did she become friends with a group of women who were a lower class than her?

OR: Yes, that was one of the fun things about working on the book, that Christenze actually thinks she’s better than the others! Haha! She’s noble, and therefore there’s a larger source material on her, and through those sources, I glimpsed other women’s fates. Christenze has a title, but she has no money, is unmarried and has almost no family. So she’s a sort of Jane Eyre figure who lives at Lady Anne Bille’s house, like a maid-friend-thing. It was actually very common in those days. I don’t know if it’s different from the British class society at that time, but in Denmark it was common to have friendships and relationships across the class divides, also because Denmark did not have a particularly large nobility.

At the same time, of course, it was quite spectacular and became great national news, that a noblewoman had been down and dirty with these women, and even became a witch along the way.

BB: Christenze is described as a virgin in her 30s who has little to do with men. Were her erotic relationships with women such used as evidence of her ‘unnaturalness’ in the real-life trial?

OR: Their erotic relationships were not used directly against them in court, as much as the idea of being loose sexually that was seen as a sign of witchcraft.

It is remarkable that Christenze never gets married, and coupled with the fact she keeps ending up in these close friendships and groups with women, yeah okay, so I started thinking. I found documented evidence, for example, that Christenze and Maren had ‘lain in bed together’, but we have no chance of knowing what that means, so it is really me who added the sapphic vibes.

At the same time, I wanted to write a relationship between women in which sexuality is something different from what we understand today, where the line between friendship and erotic relationships is blurred, not like today where we want to box everything in.

BB: How are same-sex relationships treated in modern-day Denmark?

OR: Legal equality and the protection of homosexuals have made considerable progress in Denmark. Denmark was the first country in the world to introduce registered partnerships in 1989. In 2006 it became legal for doctors to assist single women and lesbians in artificial insemination. At the same time, Denmark is not exempt from the idea that father-mother-child is the best family constellation in the world. Homophobia is unfortunately also a problem here.

BB: Does the wax child embody some kind of dark female magic? How do you express your ‘dark’ side?

OR: How do I express my dark side? I do not believe in light or dark sides. But I know that I can sometimes be in what I like to call ‘a dangerous mood’. Then I will say to my friend, perhaps its evening, Saturday, some guys will approach us at the bar (but we’re nearly 40, who do they think they are?) And then I will say to my friend ‘Oh, no, I have to be careful, I’m in a dangerous mood’ – which means that I will begin provoking people, perhaps especially men. Provoking can also mean spilling some really dirty secrets or speaking uncomfortable truths out loud. I have had real problems with this, it is something I’ve had in me since childhood, such as when the bullies came out, but I couldn’t bite my tongue. It just … slips out. I have also had problems with this when I meet very important people. For instance, I once met the Danish prime minister and immediately began to talk about breasts ejaculating milk like two big dicks. I’m sorry, I did it again.

BB: Did she bring any revelations for you as you were writing?

OR: Are you talking about the wax child? It’s so interesting to me, when people assume it has a gender. My German translator assumed the wax child was a HE! I really like that, everybody projects themselves into this gender neutral voice. And yes, yes, not only the wax child but all the women brought me revelations!

I often feel something like a spiritual connection with the past. In my research, I may find that the sources or landscape speak to me, a sort of whispering, or that they are populated with kind ghosts that tell me secrets if I listen very closely. Reading the archive or the historical site is a sort of listening. I spoke at one point to a clairvoyant who was adamant that what I was describing was actually clairvoyance, but I prefer to think of it using my intuition in the same way the paleontologist Louis Agassiz, (1807-1873), who regarded dreams and intuition as guides in his ability to reconstruct fish fossils.

BB: The story made me think afresh about how women’s bodies and biology are still sometimes perceived as disgusting or dangerous. Christenze and her friends are variously described in the book as ‘hag’, ‘sorceress’ and ‘cunning woman’. Some of the misogynistic characters delight in putting these women in their place.

OR: I do not really find the conversation about the dangerous female body that interesting. Is it really still so choking to write about the female body? After all this time? But it is true that I wanted to write some one-dimensional evil male characters in this book, haha, that was a small revenge. That was me being in a dangerous mood!

BB: Who inspires you?

OR: Oh, I think the Japanese poet Hiromi Ito has been so important to me here. She once told me: Write as if no one has any expectations to you. I return to this piece of advice all the time.

BB: I enjoyed the scenes where women get together for communal activities such as carding wool or gutting herring, and the stories they tell each other about sex, marriage, motherhood and domestic abuse. (Bring on the coven…) There’s a shiver of delight and schadenfreude relating to ‘encounters’ with the Devil. Do you have a female coven of your own?

OR: Yes, those are some of my favourites too. And yes, I actually have a coven. We meet two times a year. But I swore secrecy to it, so I can’t tell you anything else.

BB: It’s an excellent translation, by your regular English translator, Martin Aitken. Could a woman translator have approached anything differently?

OR: Martin is a genius! You have no idea! I think Martin’s understanding of poetry, language and music is more important than gender in this regard. It was more important to have a translator that understood the work done with language than the experience that is described.

BB: The Wax Child includes some wonderful spells you found in your research. Have you ever used spells yourself?

OR: Oh my god, I have done so many spells. Usually with people consenting, I must say. In the coven we do a lot of stuff together. I don’t have a favourite spell, but I love June. June is the best month for spells – at least for me, I always feel like I do some of my best spell work in June. But it’s different for everyone.

BB: Tell us a little about your family background…

OR: I was born and raised in Copenhagen, where I still live. I’m married and have two sons. My parents are both artists, my father is a painter, and my mother is a musician. I have a lot of musicians in that side of the family. I thought I was going to be a musician too, when I was a teenager. Oh, and I have four brothers, but they are all very much younger than me.

BB: What does an ideal writing day look like?

OR: I have absolutely no routine. This has become a routine in itself. I don’t have an office; I don’t even have a desk. Each time I finish a book, my husband says: ‘When did you write this, I don’t understand.’ I don’t understand myself! I like to write behind my own back!

BB: You’ve won many awards and came to international attention with a futuristic novel, The Employees, which was longlisted for the 2021 International Booker Prize. Has your head always been teeming with stories?

OR: I know it’s a cliché, but yes, I was one of those children that read all the time. It’s not that I wanted to write, but from a very early age I wanted to be close to literature. I still feel that way. I still don’t understand what language is.

BB: Which childhood book made you want to be a writer? And which adult writers inspire you today?

I think I have to say the Grimms fairy tales, in their original violent versions. Haha! I read everything as a child. I was famished for books; everything was a wonder.

Contemporary: I adore the German playwright Wolfram Lotz, and who else, I really enjoy Han Kang’s books too.

BB: You’re a much-garlanded novelist and poet in Denmark – I hope many more English readers discover your extraordinary writing, but where can they find it?

OR: I have three books published in English: The Employees, My Work and The Wax Child. I also have a substack called ‘This Mess’.

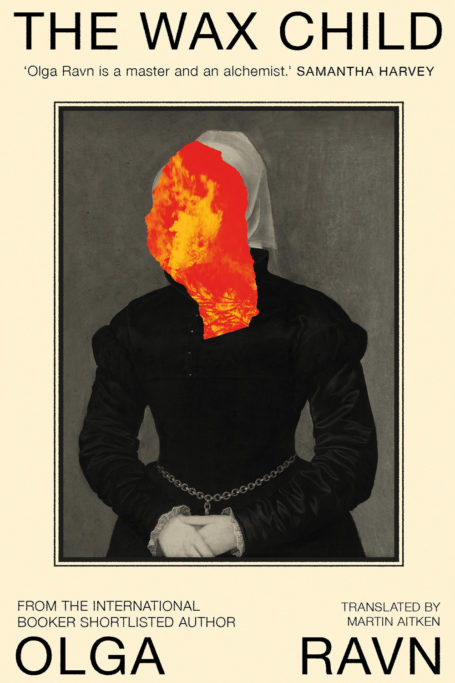

The Wax Child by Olga Ravn

Viking (£14.99)