Round The Ragged Rocks Of Northern Oman

By

10 months ago

Kate Eshelby explores the bewitching mountains of northern Oman

Emerald-green terraces punch out of the otherwise arid landscape, a vibrant miracle, as they tumble down the mountainsides. Early morning, no one else is around as I descend the steep stone steps through this tropical Shangri-La in the heart of Oman’s Hajar Mountains. These lush, tiered gardens, feathered with date palms, were hand-carved out of this rocky terrain centuries ago.

Together with my husband, Mark, and two children, Zac and Archie, we’re exploring these soaring mountains across northern Oman, staying in guesthouses. First is Misfah Old House, in the historic village of Misfat Al Abriyeen. Most of the original inhabitants have moved nearby to modern housing since the 1970s, when the previous leader, Sultan Qaboos, brought dramatic changes to the country. But the villagers still return to tend their farms, although most of the work is now done by migrant labour, mainly from Bangladesh.

We climb down a twisting path through a cascade of mud and stone houses to reach the traditional village. Suddenly, we turn a corner to a drop of gleaming green, like Oman’s own Hanging Gardens of Babylon – among which our guesthouse hides. One way to preserve Oman’s many abandoned, adobe buildings is tourism: Misfah was the country’s first old house to be turned into heritage lodging.

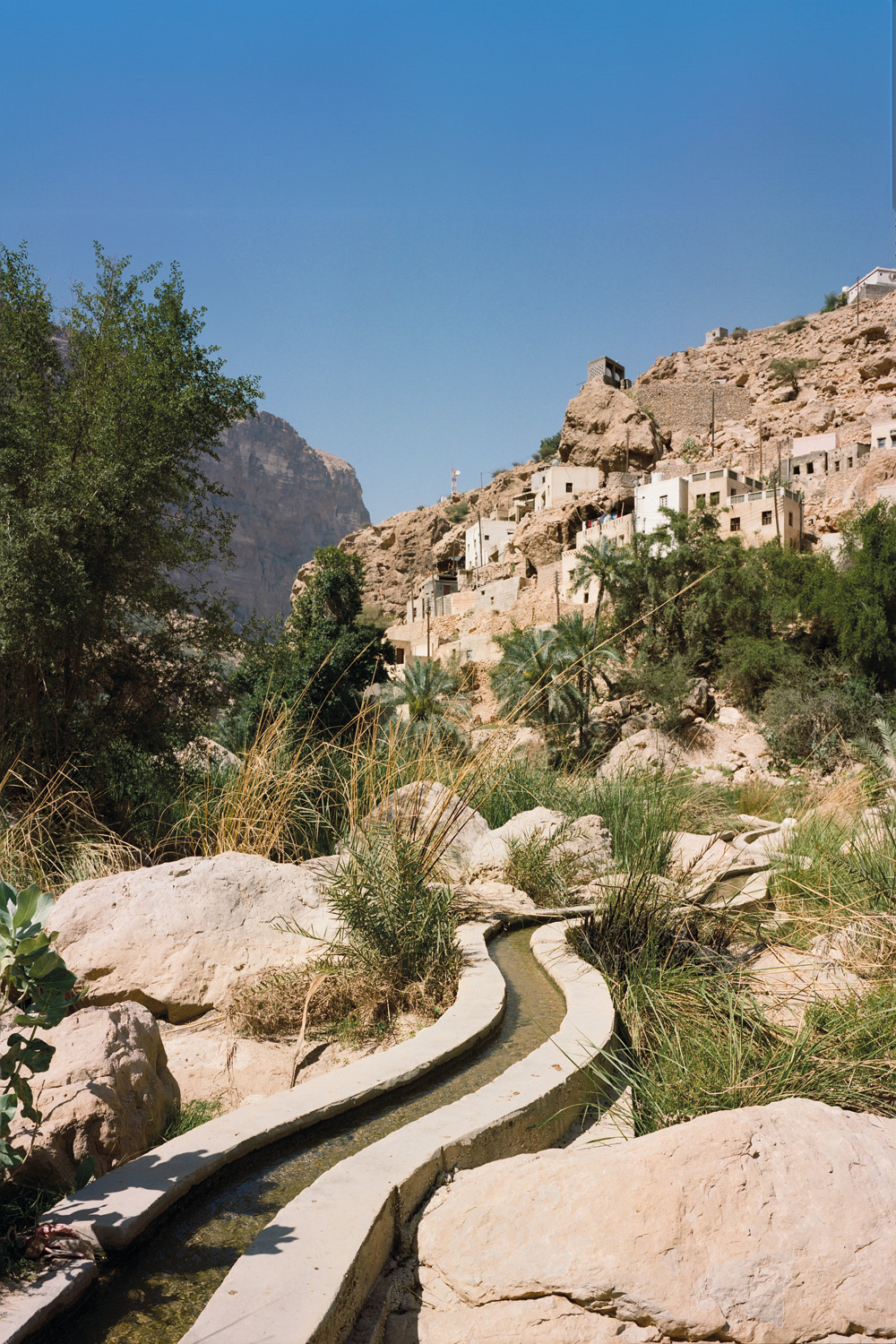

The gardens surrounding Misfah Old House (© Kate Eshelby)

Inside the guesthouse, King Charles beams out at us, from a framed photo of a visit he made here. The bedrooms have numerous alcoves carved into the walls, typical of old Omani architecture, and big clay urns, once used to store dates, stand in the corners. Meals are eaten on a roof terrace with far-reaching mountain views.

Later, Yaqoob Alabri, a guide, leads us on a stroll through the farms, fringed by aflaj – an ancient irrigation system. Water is brought up from the mountain’s deep belly, via underground tunnels, before flowing into gravity-powered channels, which curve for miles like a giant marble run. Aflaj are ubiquitous throughout Oman and five of them are recognised as Unesco World Heritage Sites. ‘The water is shared using an age-old calendar and everyone knows their designated time slot,’ Yaqoob says, clad in a long, white dishdash (the typical gown worn by men).

Not so long-ago, camel caravans still wound across Oman’s deserts carrying dates and frankincense. One of the most striking things about Oman is how recently it’s transformed.

‘Qaboos built the country from nothing,’ Yaqoob says. ‘Before 1970, we had no roads, schools or hospitals.’ And until the early 1990s no tourists were allowed to visit. Yet, even with the rapid changes, Qaboos has ensured that this oil-rich land remains a last bastion of old Arabia and the culture is proudly maintained.

Sulaiman Al Riamy sorting roses (© Kate Eshelby)

Despite its aridity, the country, which curls around the toe of the boot-shaped Arabian Peninsula, boasts a diverse landscape. You can swim with turtles in turquoise seas, climb dunes in the world’s largest sand desert, and explore cloud-forest mountains that are home to the endangered Arabian leopard. It’s also incredibly safe to travel around – although this wasn’t always the case. Oman is full of historic fortifications because of its once-rival tribes and past invaders.

One morning, we walk to Ain Al Lathpeh, the spring that sustains the surrounding farms. We pass several ruined watchtowers along the way, which once stood guard over the waterways. As we trace the aflaj, wandering amid corridors of palms that resemble verdant jungles, huge clusters of mangos hang over the crystal- clear water and our boys delight in a game of Poohsticks. Blue and red dragonflies sparkle like gems, and butterflies fill the flowers.

That afternoon, we hike around the rim of 1,000m-deep Wadi Ghul, known as Oman’s Grand Canyon, to a deserted village, constructed into the cliff’s overhang. The layers of the canyon walls frill out like a flamenco dancer’s skirts, bright gold in the evening light. Over aeons of years, water has sculpted spectacular, deep wadis (river valleys in Arabic), through Oman’s landscape – millennia ago, Oman’s climate was much wetter.

Nearby, Snake Canyon cuts into the mountains, where olive and juniper trees cling to the rocky slopes in fairy-tale-like scenery. We spend a day with adventure guide Yusuf Al Kindi, swimming through a string of pools, leaping from high ledges into the cool water below and abseiling down waterfalls. I feel alive and pumped with adrenalin. This is nature’s water park, with rocks eroded into natural slides, which our children love.

Ali Yahya Al Amri, owner of the Hanging Terraces guesthouse (© Kate Eshelby)

Our final place is the Hanging Terraces guesthouse – a sheer, two-hour drive away – in the Jabal Akhdar Mountains. Here, palms are replaced by pomegranate, walnut, and apricot trees because it’s over 2,000m above sea level. The guesthouse is the owner Ali Yahya Al Amri’s restored family home with thick, walnut-wood doors and shuttered windows. A roof terrace looks out over multiple layers of Barbie-pink rose gardens that plunge into the gorge below.

In these elevated enclaves, the age-old craft of distilling damask roses in traditional mud ovens continues. We’re invited into the home of Ali’s brother-in-law, Sulaiman Al Riamy, where a carpet of fragranced flowers covers the floor, and learn about the myriad uses of the smoky- flavoured rose water: in halwa, a popular Omani dessert, coffee, and for medicine. ‘Even Queen Cleopatra bathed in it as part of her beauty routine,’ Ali says.

As I meander back through the exotic gardens, they evoke paradise – a term originally derived from the Persian word for an enclosed garden. These vibrant places are encapsulated within the rugged embrace of the rocky desert. I just hope that as Oman shifts from oil, its new focus on tourism remains sustainable and it keeps its pristine landscapes, which are some of the most beautiful on earth.

C&TH Guide To Responsible Tourism

BOOK IT

Seven nights at the Misfah Old House and Hanging Terraces, including flights from London with Oman Air and eight day’s car-hire starts at £3,815 per person or £12,620 for a family of four (originaltravel.co.uk).

Kate stayed in Muscat at Jumeirah Bay, family suites from £670 per night (jumeirah.com).

Kate’s return flights to Oman had a carbon footprint of 6,944kg CO2e. ecollectivecarbon.com