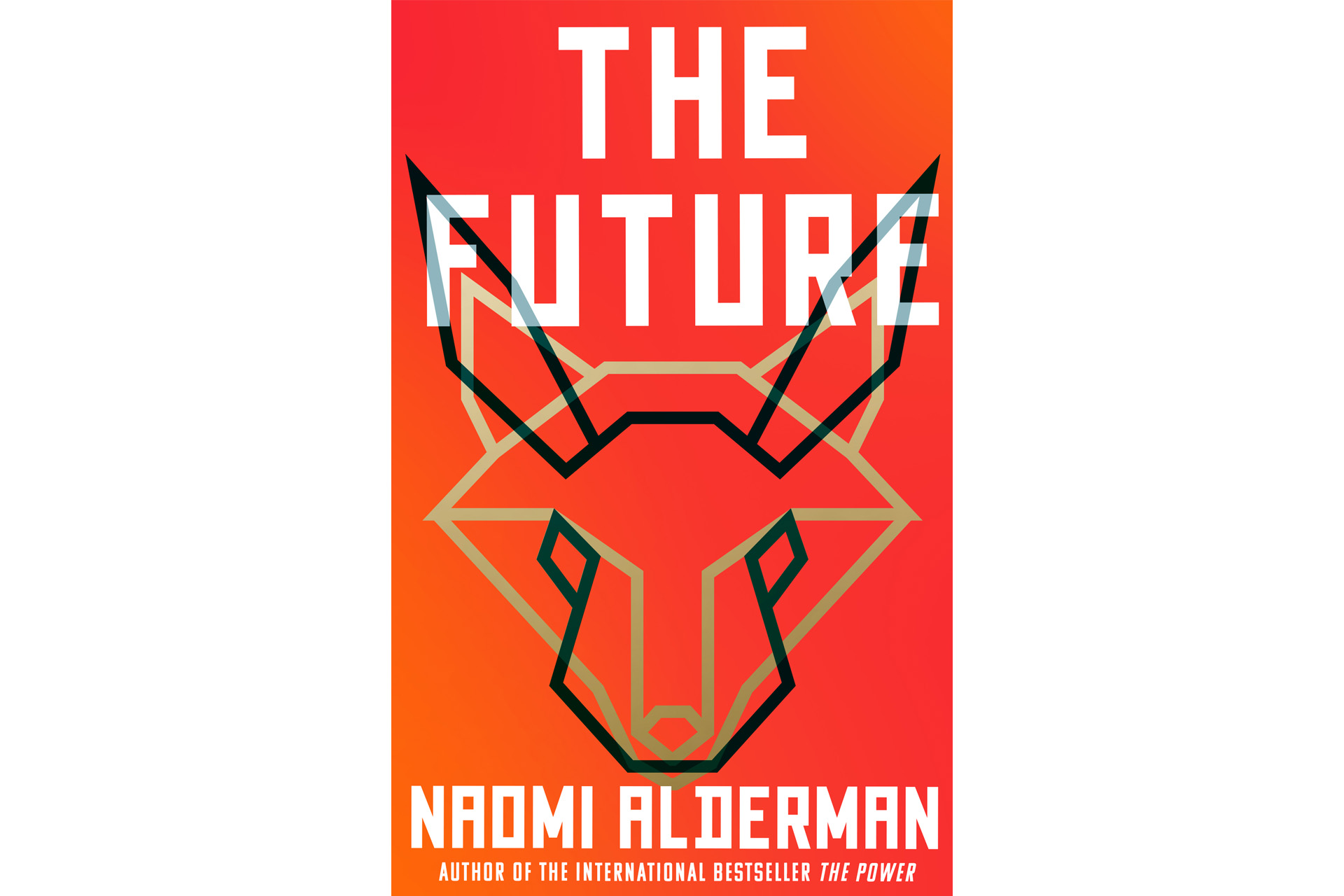

C&TH Book Club: The Future by Naomi Alderman

By

2 years ago

Enter the apocalypse

In November’s Book Club Naomi Alderman talks to Belinda Bamber about survival, sex and screenwriting – and waiting out the apocalypse with Margaret Atwood.

Main image: Annabel Moeller

The Future: An Interview with Naomi Alderman

Belinda Bamber: The Future is a thriller in which three rival tech billionaires flee to a shared escape bunker on an enchanted isle. As an apocalypse plotline it’s both deeply serious and hilariously funny. Did you have a clear sense of the story before you started writing?

Naomi Alderman: With this novel, I really had no idea where it was going. I started in a few different places. I’ve worked in technology for years – I am the co-creator and lead writer of the smartphone exercise game Zombies, Run! And it’s a fascinating and infuriating world that I’d always thought I might write something about. I read the famous New Yorker piece about the existence of survival bunkers for technocrats which caused my blood to actually sublimate out of my body with fury and horror. I was noodling around with two sets of scenes: one of someone fleeing from an assassin in a hyper-digital-consumerist mall in Singapore, and the other of someone sitting on an island with a technological survival suit for company knowing themselves to be the only person left alive after a huge global catastrophe. I just kept writing and writing and eventually it turned out that those were definitely parts of the same book. Sometimes writing is like that: you just have to keep going in the darkness until it comes clear.

BB: The novel is rich in ideas, tangents, memorable lines and light-bulb insights, not least the enduring relevance of Bible stories, in this case Lot and his daughters.

NA: I suppose the Bible part of the story – and my strong conviction that we can get a huge amount out of those books the moment we stop thinking that Every Word Is Sacred And Holy Writ – has been brewing for decades? I grew up very religious, I responded to those texts as anyone with a narrative sense and a love of language would. I just thought that the conclusions my educators were drawing out of them were in some cases peculiar. If stories are alive – which the stories in Genesis still definitely are, they’re gripping and powerful – then they belong to anyone who wants to think about them, retell them, explain what they mean in a new way. When I heard about the survivalist tech billionaires (who really exist!) building their bunkers, my mind immediately went to the story of Lot who survived the destruction of Sodom, holed himself up in a cave with his daughters and… it didn’t go brilliantly for him. I think those stories are worth knowing about because we are essentially no different – in our humanity – to the people who wrote them five or six or ten thousand years ago. People are just the same. ‘Going it alone’ is always a totally absurd fantasy. We need other people, we just do.

BB: Zhen, Martha and other women mostly direct the narrative – strong, individual, flawed, sometimes ruthless in their search of ‘global good’. Yet some of the men in The Future are also edgy, engaging, contrary and unpredictable. I note this as if readers might be surprised – do you ever want to escape the expectations/polarising debates that come with your media profile as a ‘feminist lesbian writer/gamer raised in a Jewish household’? Would you ever write anonymously?

NA: Well, the surprising thing possibly is that I actually do fancy men as well as women. I just don’t seem to have gender or sex lines on who I fancy or sleep with? I like writing about romance and sex between women – it’s been a very wonderful part of my life and I feel like the world has enough heterosexual romance now that I don’t need to push myself to contribute! I don’t *super* like saying ‘bisexual’ or ‘pansexual’ because my experience of myself has been so much more complicated than that: anyway it tends to be about the person not the genitals/gametes/gender identity for me.

Which I suppose is to say: I have the urge to slip any halter I find myself put in. I always like to try to think a bit wider than before. I suppose other people might have expectations about me. Definitely some of them try to have polarising debates with me. I try to resist that. I like Daniel Kahneman’s line (in Michael Lewis’ The Undoing Project): ‘When someone says something, don’t ask yourself if it is true. Ask what it might be true of.’

BB: Despite setting out what feels like an all-too-plausible disaster scenario for modern life, the book ultimately feels optimistic. Did your own sense of the future change in any way as you were writing it?

NA: One thing that changed during my writing of the book was my sense that we can do any good whatever by sitting down in the ashes and weeping. I think there is a lot of despair right now among people who care about – for example – the planet. And the despair is somehow narcissistic (sorry). It is a way of expressing grief, which is legitimate. But it’s also an expression of anger, rage, feeling ignored, feeling belittled. The tendency at times when we feel those feelings is to get more and more extreme – like a child who fears they are alone screaming louder and louder. It’s an understandable tendency but it doesn’t help.

The people who are deeply concerned about habitat destruction, species extinction, climate weirding are right. It’s right to take those very important questions seriously and work together on them. But not to despair yet: though much is taken, much abides. Find something and tend to it. Work on the patch in front of you.

There is a Jewish saying which I find very helpful when contemplating monumental tasks and problems like this: ‘it’s not up to you to complete the work but neither are you free to refrain from it.’ I think I worked that through for myself in writing the book. What can one do? Well, everything. Each of us can put some part of our lives (our gardens, our country towns and houses as it were…) into preserving wild nature. We can write angry letters to our representatives. We can record, we can work to preserve and most importantly we can take joy and refuge. Don’t spend so much time worrying about nature that you forget to take solace in it every day.

BB: You’re famed for your love of research – did you need to leaf through any survival manuals or tech handbooks for this one?

NA: I’m excited to know that I’m famed for my love of research! I do love it – how did that news get about? I read quite a few survival blogs and watched survivalist videos. I do have the SAS Survival Handbook in my loo. Just for light reading at moments of contemplation. And I’ve travelled about quite a bit with Margaret Atwood, who grew up in the woods in Canada and will often stop halfway down a street to point out a weed that turns out to be good for eating. She’s very skilled.

BB: The AI Suits become tangible, almost-human characters, despite (or perhaps because of) their upcycled sex suits. What are your expectations of AI as a force for good or evil? Can robots alleviate human aloneness / loneliness, as in the novel?

NA: The thing is that AI is a misnomer really. It’s a tool and not a person. And like any tool it can be used for good or evil. It’s good fun. The trouble is when we decide to treat it as a God and not as an interesting, fun and sometimes useful tool. To be honest, if you want to alleviate loneliness, getting to know all the birds in your neighbourhood, living with a dog or – you know – contributing to human communities around you are always going to be better bets.

BB: Your love of the environment and the beauty of the natural world shines through The Future. Aside from the intriguing ideas in the novel for helping humans, such as FutureSafe zones and AUGr-style wrist apps, I liked the potential of rooftop wildlife sanctuaries, streets empty of cars and car-related fatalities, wildlife travel corridors (‘leaving the tiger places for the tigers’) and 3-D helmets for virtual strolls in the jungle. Which would you choose?

NA: I have thrown all the ideas I have about this into the book in the hope that someone who can make some of them come true reads it. I promise I will work tirelessly on a board or as part of a charity to help. The thing I kept coming back to in the novel is that if we *do* sort this out, it will be so much nicer than things are right now. All we hear about these days are the sacrifices and the horror stories: cutting emissions means losing this, giving up on that, and so on. But we need to keep imagining the beautiful world on the far side. It’s so close, we could get started now and be done within five or ten years. Clean rivers and seas for swimming and fishing. Safe streets, wild birds and hedgehogs, living hedgerows in cities, slow traffic where needed and many more bicycles and tricycles (I can’t ride a bike, but I ride a trike and adore it, they are the way of the future; I would ride much more if the streets were safer for me), lots of subsidy for good fruit and veg for everyone. We will all really enjoy living in that world. We just have to get there.

I choose all of them. If you want a rather provocative one for the UK: the idea that your garden belongs completely to you and you can do whatever you like with it including concreting it over and putting down fake grass I think needs to come to an end. The land of this country is what the wild creatures and plants of this country depends on; it is a common good between all people here and all wild creatures here. You should be able to do what you like with it *within limits*. It should be like allotments: you can grow what you like but you have to be growing something or the community will take over managing it for you. ‘Rewilding’ and never cutting the grass or trimming a shrub again is fine. Having a beautifully manicured lawn with some side areas that give homes for wild creatures is fine. I’m sure there are thousands of great ways to have a space that works for you and for our natural world. But people turning their gardens into completely sterile dead boxes because they’re ‘easy to manage’ is diminishing the wild beauty of this country for everyone, and no. If you can’t manage it then someone else can do it; many would love to have the opportunity.

BB: The Future shows how global tech billionaires can be a force for good. Can fiction?

Oh I hope fiction can be a force for good. I realised the other day that what I’ve actually written here is a protest novel. Which people don’t seem to do very much with novels anymore, but is part of the history of English literature. Dickens and Wilkie Collins wrote protest novels, Elizabeth Gaskell and Charlotte Bronte and George Orwell wrote protest novels. I hope mine is *extremely entertaining* also – I believe in a very healthy helping of sugar with the medicine.

BB: Would you cope well on a deserted island and do you have any survival skills like your lovelorn heroines, Martha and Zhen?

NA: Oh dear, I’m not sure I would do very well. Part of the reason that I invented the survival suit is because I would definitely need it. Having said that, my skills are:

– I am a very good cook and very inventive and creative with cooking, I can even do ingredients e.g. I often make my own cheese.

– I still have the instinct children have to try to use objects I find in all sorts of different ways.

– I look at old milk cartons and egg boxes and see scoops and hand-puppets.

– I am very willing to learn and to collaborate – one of the plot points in the novel is that this turns out to be the supreme advantage.

BB: Who would you invite into your bunker? And what tools or comforts would you want with you?

I mean Margaret Atwood obviously: she actually knows how to survive in the backwoods. I would of course bring my family and some dear friends and if she brought all of hers that’d be a good starter community. My friend Dr Benjamin Ellis who is both a consultant rheumatologist (helpful in an apocalypse!) and also goes around the world in his spare time helping religious communities to talk across sectarian and other divides to work through difficult issues together. A doctor and a mediator rolled up in one is a *very* efficient apocalypse survival proposition. If I get to absolutely have my pick I’d definitely have the Inuit educator and expert hunter and gatherer Derrick Pottle, Dr Chief Mi’sel Joe and the Mi’kmaq Nation, Ray Mears, and the collective who run the wonderful wild camping group The Old Way in there. And all their families and friends and communities. By this point it’s basically that I’m asking the Mi’kmaq people if we can move in with them and pool resources. If they were willing to have us, we’d be *fine*. It’d be great. When can I go?

In my novel, some of the billionaires have archived all of Wikipedia so that they can access it even after the internet falls over. That feels very sensible, in addition to some extremely good knives. And for me, a VERY comfortable bed.

BB: If you could save one human quality for a post-apocalyptic future, what would it be?

NA: Curiosity. It is the best of us. As long as we can be fascinated and curious about everything – the world around us, the living things we share the world with, each other – we will be alright. It’s when we lose that, shut down and think we already know everything that it starts to go badly wrong.

BB: Are there any world leaders you would save? Should there be a balance of Foxes and Rabbits (and which would be which?)

NA: Well the thing is that we are all Fox and we are all Rabbit. But I’m trying to think of leaders of countries who I would really want in my bunker. I mean I’m sure in person most of them (most) would be fine. But I’m with Douglas Adams: anyone who tries to become very powerful ought probably ipso facto be excluded from power.

BB: You’re co-creator and lead writer on the long-running, popular reality fitness game, Zombies, Run! with games developer Six to Start. Do you still write in the mornings and game in the afternoons? And will any of the remarkable female scientists you’ve discovered as a BBC Radio 4 presenter of the history of science inspire future novels?

NA: Haha yes I do feel not-quite-right if I don’t have two projects on the go at the same time. TikTok tells me I probably have ADHD but I’m going with it. I’m actually starting work thinking about a new game now. As well as a new novel. The history of science hasn’t turned up *yet* but nothing is ever wasted so probably they’ll pitch up in the future….

BB: Has the screening of your earlier work impacted your novel-writing process? Disobedience was turned into a 2017 movie (produced by and starring Rachel Weisz) and The Power became a TV series that you co-developed, including writing episodes. I note The Future has pivotal scenes that would translate brilliantly to the screen, including the gripping chase sequence in the mall, the drone attacks, and the exotic, tech-equipped island refuge.

NA: I definitely found that writing for TV at the same time as writing this book shaped the writing process in some interesting ways. I learned a huge amount about character from working in TV: whatever little hints you give about character in a novel, TV writers will dig down into deeper and deeper, really getting to understand everything about that person. I think that was an incredibly useful discipline. And yes, when you see your work translated into film you can’t help but start to think in a more visual way. It’s all grist to the mill.

BB: Given the breadth of your experience, would you now seize the chance to direct The Future yourself?

NA: Oooh. Maybe *an episode*. I have always felt that when presented with many options in the buffet of life: pick the one you never tried before. This has led me to be out of my depth over and over again, but also has taken me to places I’d never have visited if I’d stayed in the shallows.

BB: Margaret Atwood mentored your early work. Which other writers are important to you?

NA: Too many to name, of course. But writers I’ve read or re-read recently whose work is vital and glorious include: Musa Okwonga, Penelope Lively, Tolstoy (I know you may have heard this before, but War and Peace is *really good* – but please read the Dunnigan translation over all others), William Golding, Chinua Achebe, Janet Malcolm, David Graeber, Ursula LeGuin, Diana Evans, Louise Erdrich, Ted Chiang and Alison Bechdel. You won’t go wrong anywhere there.