Daisy Hildyard On Writing For The Climate Crisis – Interview

By

2 years ago

Ahead of her panel at London Literature Festival

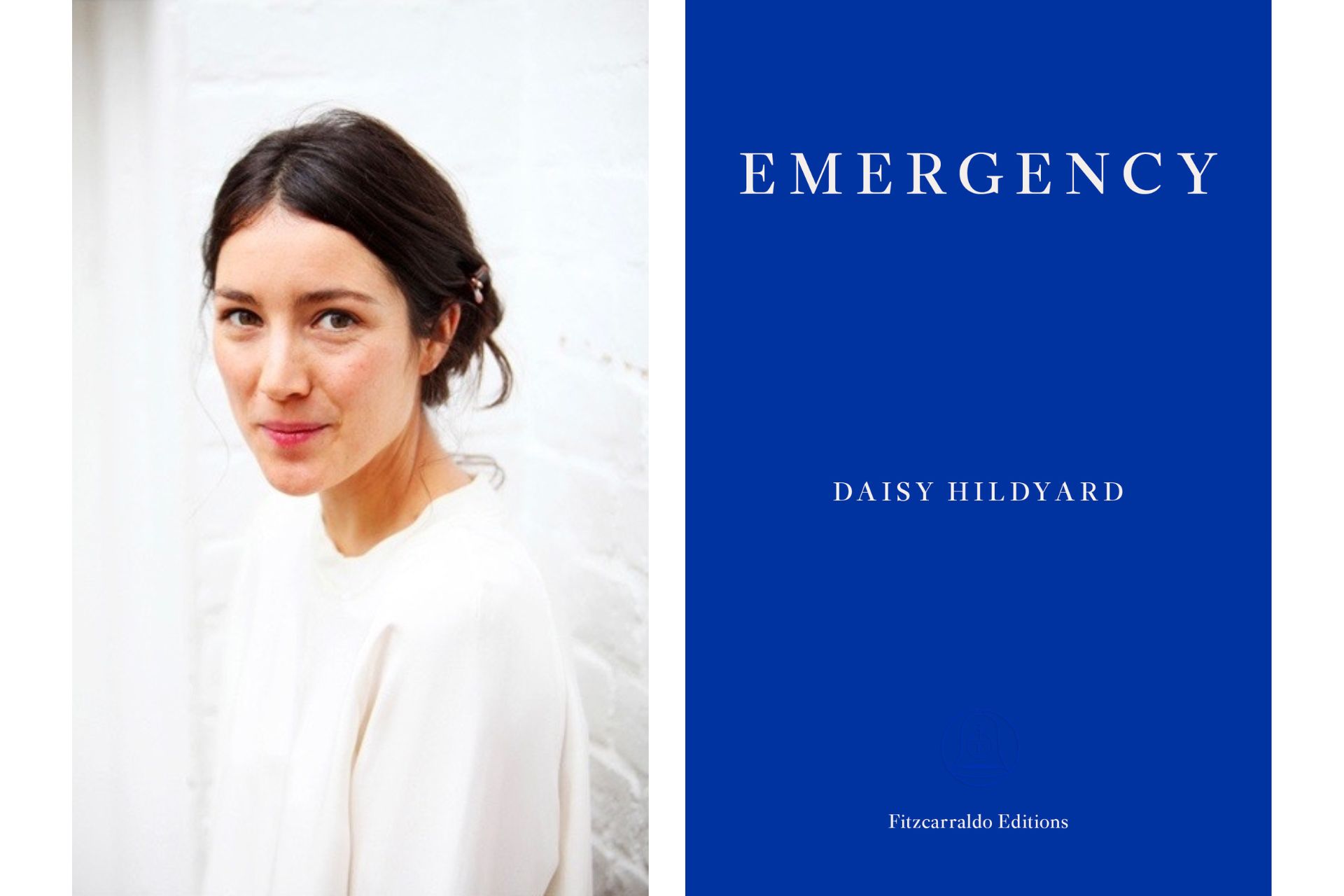

The Royal Society of Literature has awarded Daisy Hildyard its 2023 Encore Award for her sophomore novel, Emergency. Here we look back on Tessa Dunthorne‘s interview with Daisy about writing for the climate crisis.

© Barney Jones/Fitzcarraldo Editions.

This article was originally published in September 2022.

Daisy Hildyard On Writing For The Climate Crisis

Daisy Hildyard’s first novel Hunters in the Snow received the Somerset Maugham Award, and her essay The Second Body won The White Review’s Book of The Year 2018. Her second novel Emergency discuss the relationships between people and ecosystems in the wake of the climate crisis – through a surprising setting of 1990s rural Yorkshire. Daisy Hildyard is one of the brilliant authors lined up for London Literature Festival as part of its climate strand. She talks to us about what she’s writing now, how she copes with the enormous responsibility of climate change, and Greta Thunberg.

How are you doing? What are you up to at the minute?

Oh man, that’s not a question I’ve been asked for a while! I’ve been working on some new fiction about a Greenland shark, and some set in London. And then an essay which deals with conflict in the environment, how war changes landscapes.

That’s really interesting. Have you been talking to many people about this to research it?

So for the essay, I’ve been speaking with people who monitor conflict in the environment, analysts or people who works for NGOs, who use very complex satellite technologies to look at landscapes from a distance and try to work out what’s happening in them.

One memorable conversation I had was with somebody who works for Amnesty, who is creating a report into the bombing of the theatre in Mariupol in Ukraine – and she was talking about how they work out what kinds of explosives went off, what happened in the theatre, what happened to the people in the basement, etcetera. They do this by looking at all different kinds of things that you wouldn’t necessarily expect, like the ways the trees had snapped in the square outside, the way bombs leave marks on the snow. Different kind of archives, traces of evidence on the landscape.

I’ve found myself really interested in how that technology affects the way the analysts look at these occurrences… Their feelings about it. I think she finds it really hard to look at this stuff every day and then kind of… close the laptop and, you know, go and see mates or something, and it’s just a weird experience of being in the world that I think connects with a lot of us.

And we’re obviously here to talk about the London Literature Festival – can you tell me a little bit about what you’ll be doing?

So I’ll be doing a panel with Jessie Greengrass, who’s also written a novel that is using fiction to think about the climate crisis – and human relationships with the climate crisis, plus the environment more generally. My novel Emergency is not about the climate crisis in the way you may think about it – as some kind of fireball, flash flood or disaster, but told through stories about humans and animals in a small area of rural Yorkshire. And then Jessie’s novel is a dystopian fiction. So we’ll explore how we live with climate change and how we respond to it.

I actually wondered how you translate environmental concern to a reader?

I guess that’s always the job or task for someone who wants to write fiction, how you make people want to turn the page… You have to persuade people to spend time with it. Even though I write and think and talk a lot about the environmental crisis, I still find it hard when people have this kind of lecturing mentality because, you know, it’s just hard to think about it all the time. Like, you know, you’ve got to get the dinner on – just real life.

Your essays also talks a lot about the significance of individual actions – like, if I pop down to the shop and get a Fanta there’s a political significance to that choice. How do you think we grapple with that much responsibility?

Yeah, like how delicious is a Fanta? Do I really, really want it? I don’t know… How do you sort of deal with that? Do you have a way of explaining it to yourself – or habits that you’re changing – or do you just try not to think about it? I feel like there’s this huge range of different ways that people respond to it.

I suppose we all need to find an individual answer alongside a collective one to that dilemma.

Yeah, and to do it responsibly, and with consideration – but also to find a way to have a really joyful, flourishing life, rather than for it to be a question of painful denial. Because that is never going to happen or work, I guess.

You’re very immersed in this field, you’ve got a PhD in the history of science, I wondered if all the research you did for Emergency and The Second Body, not to mention the novel you’re writing now – has it changed how you understand and interact with animals?

I do come from a meat farming background. I have a respectful working relationship with animals. I’m not vegetarian – although I don’t eat a lot of dairy, and I don’t particularly like the meat industry. And then the more I think about the fact that I don’t particularly like the dairy or meat industries, the more I find it harder to justify those practices. I pay a bit more attention to animals, I’m just more aware of their worlds going on around my world. Not only in this sort of nature – scenes of cows and trees in a landscape – but also inside my flat or whatever. That every surface has life on it. There’s something at stake everywhere.

A kind of expansion of your interior world?

Or maybe an expansion in my understanding of the exterior world? But yeah, definitely. Maybe in some sense it’s a diminishing sense of the importance of my own consciousness, because it’s like… you notice all this other stuff that’s going on outside. It’s nice to also notice all this liveliness everywhere.

A bit of a morbid turn but I found your language around animals, particularly dead animals, interesting, like how you refer to it more as bodies and corpses. You don’t often hear that framing.

Yeah, I think there’s a bit of a movement towards that, even in academic circles. We used to refer to animals as ‘it’, but increasingly we’d give animals some personal pronoun. I think these little changes in language can be a sign – a hopeful sign. I think.

Do you think there’s an ability in language to change our perspective on the world around us?

I hope so. Certainly one thing among other things; I wouldn’t say, you know, the novel is going to solve the climate crisis. But yeah, I have faith in language to do some change in its own way.

And in terms of the power of your own language, if someone were to read Emergency, is there one thing you’d want them to take away from it?

I think the sense of the liveliness of everything. That everything has a story going on around it. Almost every novel I’ve ever read, and I love to read novels, has a very contracted world, and there’s so much that these stories leave out. But in any story, there’s other stuff going on, you know – minor characters have stories going, and then also the plants, animals, you know, the earth itself. But we don’t habitually notice them. And it’s just such a delight to notice them. So I hope that within and beyond my novel, whether it’s the contents of the novel or just the feeling of busyness and liveliness, that’s what people feel and think about. Because it’s great. It’s really, really nice.

And any advice on living a life in balance?

Slowing down and giving things up can be really nice. There’s always a pressure to progress and achieve in our culture. I think that sometimes giving up and slowing down is really fun – and really good for everything and everybody. Maybe I’m just innately lazy.

Anyone who has written a book – let alone multiple – can’t claim that they’re lazy.

Oh, I’ve done this over a very long time. And it’s what I like doing. So it’s a different thing.

Finally, anything you’re looking forward to at London Literature Festival?

It’d be amazing to see Greta Thunberg… I’d love to see her on tour, too.

Yes, I reckon that’d be a kind of gig crowd.

Definitely. What’s admirable about her is that she’s so clearly not interested in that, but just the contents of what she’s saying, how she gets it across. And that’s impressive in anybody, but particularly in such a young person.

Daisy Hildyard will be talking about the imminent emergencies of everyday life with fellow author Jessie Greengrass at London Literature Festival. Catch them as part of the festival’s climate strand at the Southbank Centre on Saturday 29 October.