C&TH Book Club: The Go-Between by Osman Yousefzada

By

3 years ago

Delving into the fashion designer's compelling coming-of-age memoir

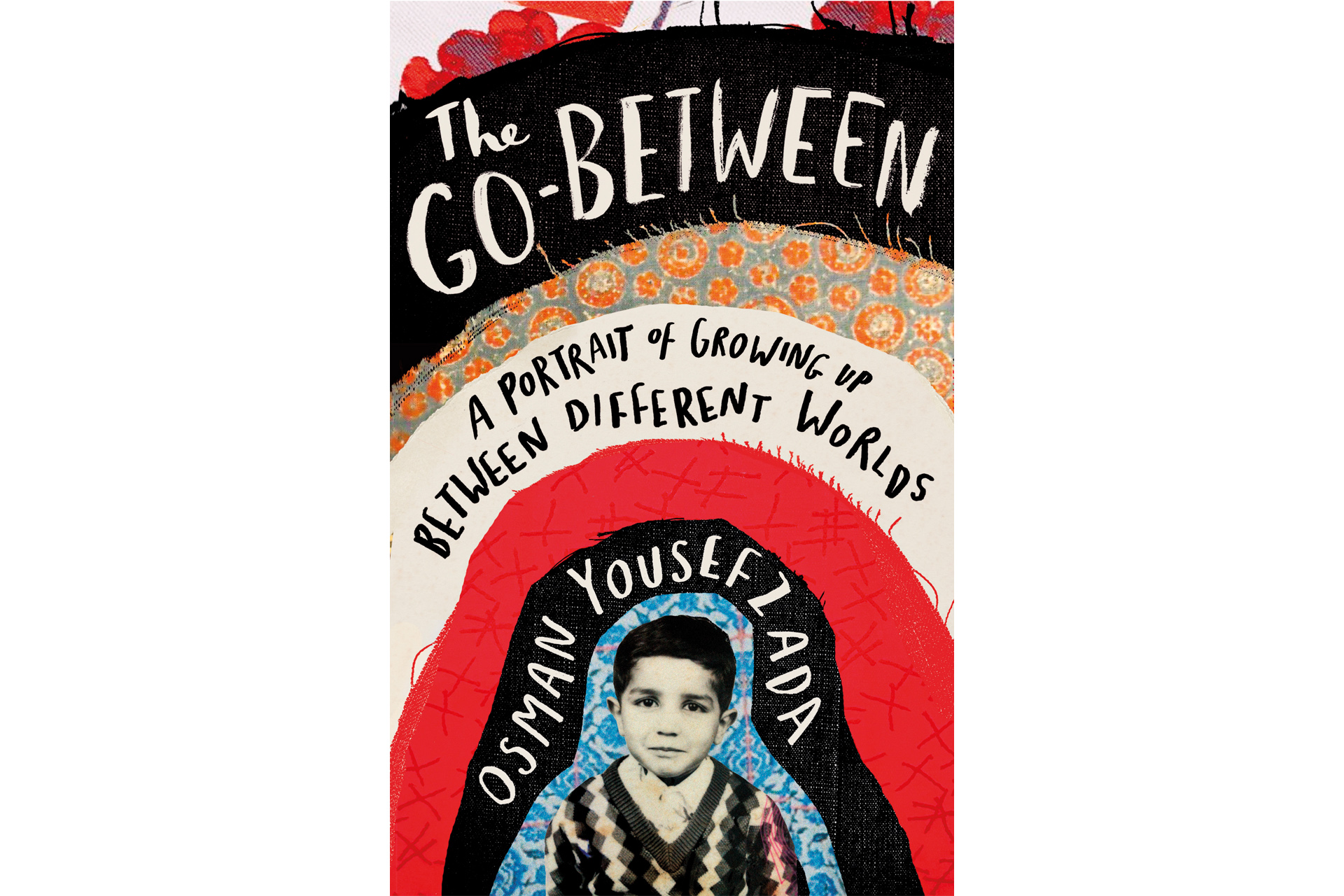

The Go-Between is a coming-of-age story by writer, artist and fashion designer, Osman Yousefzada: a vivid evocation of growing up in an Ultra-Orthodox Muslim household, slap bang in the middle of Birmingham’s red-light district.

The Go-Between by Osman Yousefzada

The Go-Between is an uplifting read, despite the hardships you describe as the child of Afghan-Pakistani parents living and working in Birmingham in the ’80s and ’90s. The young Osman is a keen observer, with a gift for humorous detachment. What came up for you when you were writing it? And how did you remember events with such clarity?

I think it’s the power of the introvert, you keenly observer others and your surroundings, letting extroverted people do the talking. I remember most things: faces, places, colours, stories, like a data bank. To some extent I have the memory of an elephant. I created a world inwards, where I stored all those thoughts and observations. The book is told through a child’s eyes, someone who is non-judgemental, who just accepts and takes in their surroundings.

Although young Osman seems closer to his gentle mother than his violent father, the father-son relationship felt paramount by the end of the book. If he was still alive, would you have let him read it?

The older I get the more I look like my father. I always thought I looked liked my mum, at least I wanted to. My dad was a complex man, a provider for his family back home at the Frontier as well as for us. Both my parents were illiterate but they were creative and good at making things: my mother as a dressmaker and my father as a carpenter. My father came over as part of the wave of immigrants invited by Britain to fill the stark gap in the post-war workforce. He was made unemployed after the factories shut down in the ’80s. He didn’t have skills to navigate his environment – he had come from a deeply conservative background, and then moved to Britain, a very different country. He and fellow Pashtuns lived in close proximity to other races and cultures in the mixed community of Birmingham, but were always seen as migrants, who were not embraced. Overall… I think he was a pioneer: he couldn’t read or write, he didn’t have the skills to integrate. But he made an inter-generational sacrifice that allows me to be who I am today.

The religious values you grew up with pervade the book, though by the end you’ve left home and started living the ‘parallel life’ that led to the career for which you’re now famous – major art shows and designing Grammy outfits for the likes of Beyoncé. Do you still go to mosque? Do you have moments of fearing hellfire for your present life and values? What legacy has that moral framework given you?

I still consider myself a Muslim, albeit more of a Sufi one. I still live a parallel life, as a creative and as an observer, you always do. I don’t fit in most places. I’m a bit of loner, but I contradict this by wanting to go to parties, though never as the centre of attention. I still go to the mosque, and I find solace in ritual; I try and search for understanding and belonging in belief systems.

Given the book’s powerful theme of male / female division in Muslim society in Birmingham (including your sisters cloistered at home and kept out of education), what is your take on the recent toppling of Kabul, the restoration of Taliban rule and re-confinement of women?

I find it incredible that we talk about rights in Afghanistan when the geo-political dynamics are so wrong – when people are hanging off planes to get out and are allowed to fall to their deaths. It shows life is so cheap in the Third World. In Afghanistan the intervention of 20 years of nation-building has been misguided in its local partnerships, leading to elitism and corrupt systems. Then the USA government just decides to abandon ship. The media talks about rights, and minorities, the rights of creatives and the freedom of the media, and a lot of this has been going on for a long time. What needs to be brought to global attention is the duplicity of non-elected government institutions who have supported Isis, and the Nusra Front, and funded them for geo-political control. When these organisations can’t be controlled, or their allegiances checked, they turn around and bite the hand that funds them. It’s a complete mess. But I live in hope that women are stronger than 20 years ago, that they won’t be beaten into submission like before – that the world has changed and the people of Afghanistan have seen the world through a different lens. We must all support them!

The book opens up a beautiful perspective on multi-cultural Britain, in which you describe immigrants as bringing colour to the grey streets of post-war Birmingham. And by multi-cultural I mean not only race and religion but also people from different walks of life, different values. What is your vision for multi-cultural Britain going forwards?

I see the book as a story of someone who is different, an outsider trying to understand his surroundings, being from the wrong side of the tracks, the wrong class, in a red-light district, from the edges of a society that is ignored. I would like politicians to read it. I think the more inward we look post-Brexit, the more problems we have. We still think we’re an Empire and can survive without our neighbours. I think the layering of our society is what enriches us.

The Best Literary Festivals of 2022

As a multidisciplinary artist, how do you manage to spread your talents between writing, art, fashion and more? Is there a sense in which you’re a ‘migrant’ between these different worlds?

Great question. I see myself as someone who doesn’t fit in. The system is really about creating a brand, you’re known for one thing and then you can sell it. That is how capitalism works. As a creative I don’t like to be hemmed in: I paint, draw, make and write. If I needed a brain surgeon I would like an expert, but as a storyteller I work across different mediums.

As a film-maker, would you direct a movie of your story?

I don’t know if I want to direct… the older I get the more I want to take ownership of my own output, I want to work with my hands. I’m currently working for myself rather than in an industrial chain, from writing to making works on paper… I want to have sovereignty over my trade and output. I make short moving images but I don’t know if I want to make a feature film. Generally, my rule is if it doesn’t come naturally, I won’t try! Text, drawing and making stuff is enough.

I was impressed by the detachment of the narrator: despite the continual racist insults, riots and other violent episodes inside and outside the home, you don’t invite pity, nor project anger onto the reader. Do you have a tip for would-be memoir writers?

I’m an observer by nature. My family says I sit on the fence, but then I can get upset. I grew up being told never to show off, so somehow you feel you should never take up space, be it in situations or conversations, but let others have space. You blend in. For me this works with my personality. I think you have to be true to yourself.

Your childhood experience as a go-between across different worlds was in some ways a foundation for your adult life as a multi-disciplinary creative. But what is the personal legacy of that split? Do you still feel an outsider despite your success? Would you change anything looking back?

I have to compartmentalise my life, show different parts of me to different audiences, to protect myself. I have never shown my complete myself until now. I still feel I don’t belong. As a creative you have to deal with imposter syndrome. I don’t think I would have changed much, maybe found a safe place for me to be more creative, as it takes years to build up who you are, and when those worlds are so separate, it can build walls. I would also have wanted my childhood to allow for a longer existence in the world of women, and for gender roles to have been less of a focus, but in some ways I wouldn’t be who I am now if I hadn’t had my experiences.

Can we look forward to a sequel?

This is a period of time that I need to keep talking about, before it’s forgotten. Historically, it was the foundation for a lot of communities today. I’d like these stories of misfits and dreamers to give people hope. I don’t know about a sequel, but there are other stories I would like to tell.

The Go-Between by Osman Yousefzada is published on 27 January 2022 (Canongate, £14.99). Pre-order at amazon.co.uk

READ MORE:

Afghan Crisis: How You Can Help / The Insider’s Guide to Birmingham