The Jewellers Mining British History for Inspiration

By

4 years ago

Past meets present in these skilled jewellers' workshops

British jewellers are adept at delving into our history and spinning it into the heirlooms of tomorrow, says Francesca Fearon.

The Best of British Style – Fashion, Beauty, Brands & More

British Jewellers Resetting the Past

Queen Elizabeth I (The Ditchley Portrait) by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, 1592. National Portrait Gallery, London

Hanging in the National Portrait Gallery is a magnificent portrait of Elizabeth I at her most majestic. Painted in 1592 by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger and dubbed the ‘Ditchley Portrait’ it presents one of history’s most powerful rulers in her prime. Resplendent in her virginal white gown, embellished with pearls, precious jewels and the Tudor red rose, you cannot help but be inspired by the exquisite detail.

Portraiture illustrates how jewels have always been symbols of power and wealth, but also of opulence and creativity, and so museums and art galleries are a treasure trove of ideas and inspiration for designers today. As jewellery passed down through the generation, it is so often broken down and a re-used in new designs, very early examples of period jewellery rarely survive, and so portraiture is a valuable historical document of style through the eras. As in fashion, jewellery designers look to these illustrations of the past for inspiration today.

This Jewellery Auction is Raising Funds for Afghan Women

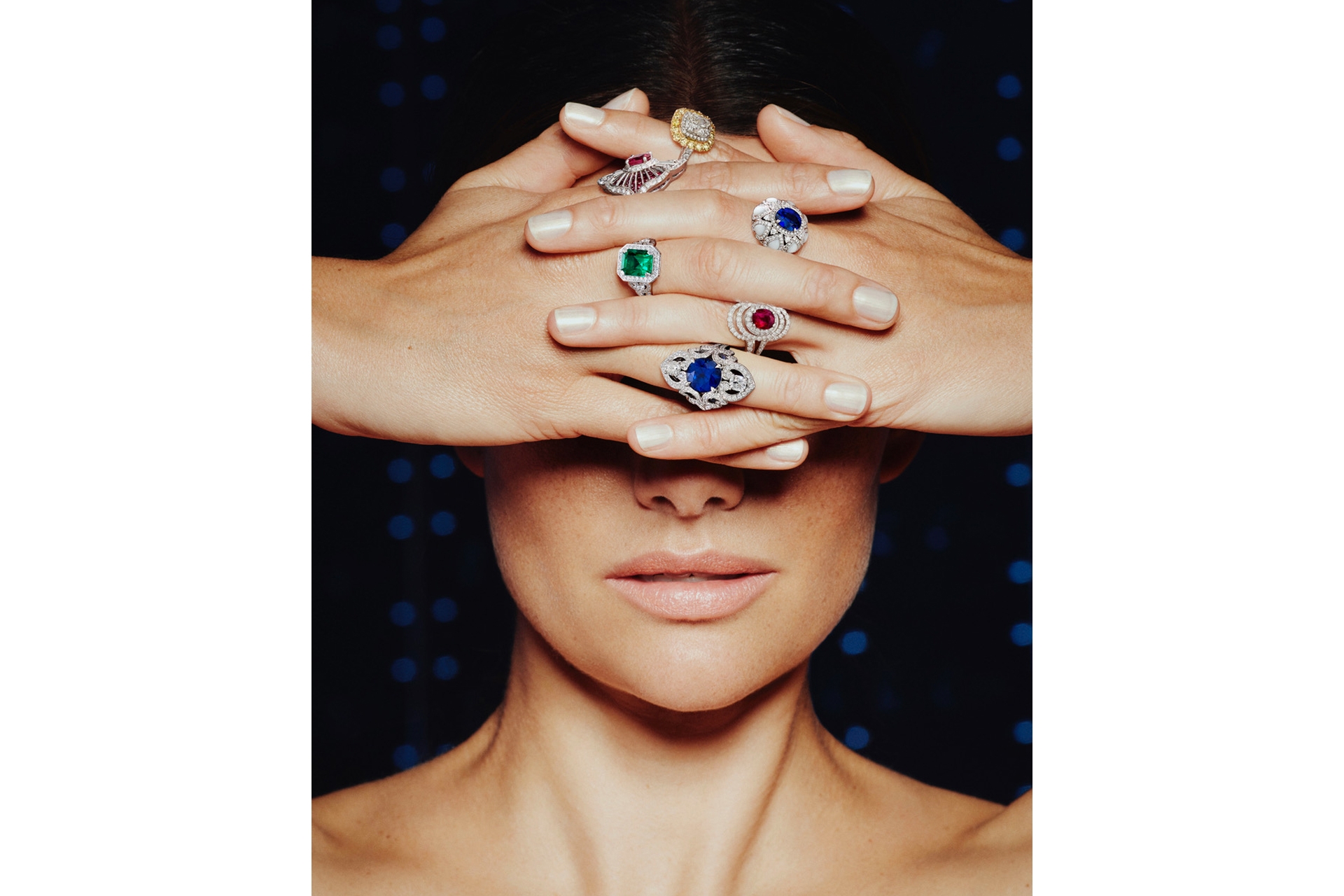

Pieces from the Jewelled Vault, by Garrard

There are fabulous historical photographs and a rich record of the sumptuous jewels once owned by Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia in the archives at Garrard. In 1874 the Grand Duchess married the second son of Queen Victoria, Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh. As the new Duchess of Edinburgh, she continued to build on her already magnificent collection with new pieces commissioned from Garrard. The collection was famously housed at Clarence House in a heavily guarded walk-in vault organised by stone colour. Intrigued by this arrangement, the trove sparked the idea for the Jewelled Vault, a new collection of unique pieces from the house, inspired by the Duchess’s jewels.

Creative director Sara Prentice’s designs echo the motifs and finer details of the Duchess’s collection and are set with gemstones – royal blue sapphires, pigeon red rubies or Colombian emeralds – grand enough to catch the eye of Maria Alexandrovna, were she still around.

The Belle Époque, an era rich with spectacular jewels as historical photographs attest, sparked Boodles’ Vintage Lace suite, now one of the jewellery house’s contemporary classics, with its beautifully scrolled motif spinning its circles around not just the neckline but five luscious red rubies. It was the era of Art Nouveau, an intense and flamboyant period in the visual arts, its graceful, swirling, stylised and arabesque forms as popular with gold and silversmiths

as they were with architects and furniture makers.

Hamilton & Inches, founded in 1866, was well situated to make the most of that era then, and now. ‘The tide of design carries with it all of history and its influences,’ says Jilly Pollard, valuer at the Edinburgh-based jeweller. ‘In Hamilton & Inches’ jewellery and silver there has been evidence of the whiplashes of Art Nouveau, the angles of Art Deco and the fine millegraining of the platinum Belle Époque jewellery.’ Platinum, she points out, was tricky to work with, needing high temperatures in order to get the best out of it, ‘but once that was overcome, very delicate jewellery could be made that had the strength to carry stones in a way previously inadvisable.’

Hamilton & Inches Signature diamond pendant in 18ct Yellow Gold, £7,250

The romantic vintage vibe of some of Stephen Webster’s work over the years is rooted in the Belle Époque and Victorian Gothic periods, such as the thorn diamond bracelets in blackened gold he was designing ten years ago.

The results, of course, were much more rock chick than dowager duchess.

Making essentially Victorian-inspired jewellery was how he learned his craft and since those early days: ‘I’ve always found it easy to draw inspiration from the various incarnations of gothic,’ says Stephen, citing architecture, colour (shades of black, red or purple) and storytelling, for ideas. ‘So many writers from the Victorian or Victorian Gothic Revival periods wrote of fantasy or real-life circumstance which have remained relevant or can be reinterpreted – but

I combine my preference for the romantic and gothic with a sense of fun and, even, irony.’

Stephen Webster’s Magnipheasant collection

The Magnipheasant collection colourfully exploits another favourite motif of the era, the feather, for sleek tremulous pavé set earrings and pendants. There is also his opulent Belle Époque collection of dramatic earrings, cocktail rings and statement cuffs featuring bright emeralds and sapphires embedded in a blanket of dark black diamonds.

Although new technology and materials are modernising jewellery, the heritage of craftsmanship is integral. The exhibition of the Cheapside Hoard of Elizabethan and Jacobean jewellery in 2014 revealed that the traditional goldsmith’s bench has changed very little since the 1500s, and that fine jewellery is still the fruit of individual master craftsmen.

Although not a goldsmith herself, Jessica McCormack makes a point of supporting that heritage and using Victorian and Georgian techniques to make her resolutely modern jewellery. ‘They have become my trademarks,’ she says. ‘This period produced jewellery of unique and unparalleled beauty. Georgian goldsmiths always used gold alloys of 18 carat and higher and each piece of jewellery was entirely handmade, ensuring that every millimetre was carefully considered.’

The daughter of an auctioneer in New Zealand, McCormack grew up surrounded by piles of precious objects ranging from Maori carvings to Georgian and Victorian jewels and naturally inherited her father’s passion for interesting and unusual antiques. The techniques she learned in her formative years are now her trademark, such as the cut-down settings used by the Georgians, which she might use to set a pair of emerald-cut diamond earrings in oxidised silver, and the Victorian Doublet which provides a sleeve of yellow gold applied to the back of white gold. Having an in-house workshop means that she can train up a new generation of craftsmen to preserve these precious techniques.

Elizabeth Gage tanzanite and diamond Agincourt ring, £24,120

Elizabeth Gage is another jeweller to walk in the steps of others from the past, learning from Tudor and Renaissance jewellery, until she could walk alone with her own vision. One of the very first pieces made in the 1960s was her Agincourt ring set with amethysts and peridots. The idea came to her as she was wandering around the British Museum and wanted to make a ring for herself. The gem-set Agincourt, Charlemagne and Templar rings became her signature designs, their history steeped in French history.

‘I make them using techniques of the period, but changing them where I need to,’ says Elizabeth. A lot of her ideas come from her imagination, ‘but having spent so long in museums, what I do has become second nature. None of them are copies, merely enlarged possibilities that have stimulated me.’ The sun, the moon, the acanthus and other historic motifs are conjured up in so many different ways. They might be created with enamels, or gemstones set in the traditional way on the Templar rings, with rub-over settings, as opposed to claw, which makes a statement of the stones.

Posy rings and message pendants inscribed with sentimental words, sonnets and quotes in beautiful gothic script are also experiencing a revival. The original designs were particularly popular between the 15th and 17th centuries in both England and France as lovers’ gifts. Originally, they would be written in Norman French or Latin, but in English too since the Victorians. Drawing on this tender slice of jewellery history, Cassandra Goad has come up with a series of quote pendants with phrases like ‘Be Brave my Heart’ and ‘Love the Life’.

Cassandra’s designs tend to be a witty play on 18th and 19th-century architecture found on her travels, such as her St Xenia of St Petersburg gold cross or earrings based on the wrought ironwork of a Sicilian cathedral, so the quote pendants are a charming departure for her. Nevertheless, these designs and those of peers are all examples of how history and craftsmanship are still among the tools of our contemporary jewellers.